Up Close: Kris Waldherr

Not Your Typical Frankenstein Retelling

You may think you know the Frankenstein story: A disturbed young scientist creates a living man out of the dead, but his Creature runs amok in the deadliest way imaginable, wrecking the life of not just Victor Frankenstein but those he cares for most. But now, thanks to Kris Waldherr’s gripping novel of historic suspense, you will enter the story from a whole new point of view: that of the women in Frankenstein’s life.

Waldherr’s first novel, The Lost History of Dreams, won praise for its gothic atmosphere and suspense. UNNATURAL CREATURES also excels in its evocative atmosphere, adding chills to the mix. The central characters in the Frankenstein story show new depth and nuance—and have shocks of their own to deliver. Historical Novel Society in its review said, “Literary but also an engaging page-turning read, UNNATURAL CREATURES is a splendid achievement from a writer at the height of her powers.”

We caught up with Waldherr, who lives in New York City with her family, to find out how she pulled off this feat.

When did you first read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and what was your impression? How did that view of the novel change in future readings as you developed your own idea for UNNATURAL CREATURES?

I first read Frankenstein when I was in sixth grade—I recall buying a paperback of it at a Scholastic Book Fair, of all places. At that time, I had no preconceptions of Shelley’s novel except that I expected the monster to be deeply scary. In some ways, Frankenstein is a genre unto itself. It’s generally credited as the first horror and science fiction novel. Frankenstein is also a rather masculine novel despite being written by a teenage girl: Frankenstein’s three narrators are Victor Frankenstein, his monster-creation, and Robert Walton, the Arctic explorer who encounters Victor en route to the North Pole.

My intent with UNNATURAL CREATURES was to write something entirely different: a feminine reimagining of Frankenstein. As such, UNNATURAL CREATURES is told through the eyes of the three women most affected by Victor Frankenstein and his monster: Victor’s bride Elizabeth Lavenza, mother Caroline, and maid Justine Moritz.

During my first read as a child of 12, I found the Creature to be incredibly sympathetic and articulate. I’d expected him to be a grunting brute, like the Boris Karloff portrayal. I also recall my shock when I realized that Victor’s wedding night would not end happily—I truly had no idea where Shelley was leading us. My main shift over the years has been a loss of sympathy toward Victor Frankenstein, who really is the ultimate Tech Bro, as a friend put it. I’ve also come to the conclusion that Frankenstein is the ultimate parable about the dangers of bad parenting. Perhaps this is a result of my now being a mother myself, but it stuns me how many neglectful, abusive, and absent parents there are in Shelley’s novel—and this is without including Victor Frankenstein and his monster-son.

How much do you think Mary Shelley’s unusual life contributed to the power and individuality of Frankenstein?

Portrait of Mary Shelley by Richard Rothwell, painted 22 years after the 1818 publication of Frankenstein

Quite a bit! I do believe Frankenstein was inspired by the absence of Mary Shelley’s mother, the feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft, who died of puerperal fever 11 days after giving birth. This maternal loss is entrenched in the lore of Mary Shelley’s life. There’s the famous story of Shelley learning to write by tracing the letters on her mother’s gravestone, Shelley losing her virginity to Percy in the cemetery, and so on. In addition, Shelley’s first child did not survive infancy. Soon after her daughter’s premature birth and death, she wrote in her journal of a dream where “my little baby came to life again; that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire, and it lived.” (Emphasis mine.) Even the names of the characters in Frankenstein are drawn from Shelley’s life. Percy’s nickname in university was Victor; he had a sister named Elizabeth; William, Victor’s youngest brother, was both the name of Shelley’s father and her son.

As for my writing of UNNATURAL CREATURES, I definitely used elements of Shelley’s life to develop my characters: her tumultuous romantic relationship with Percy Shelley, her experiences with natal loss, her complicated history with her mother, father, and stepmother, whom she didn’t get along with well. When Mary ran away with Percy Shelley, her father William Godwin essentially disowned her, though they later were reconciled. She spent much of her life trying to win his approval and even dedicated Frankenstein to him.

This was obviously Mary Shelley’s first novel, and she was quite young. What do you think of the depth of the characters and in particular the female characters you expand on in your book?

Interestingly, I find the Creature to be Shelley’s most fully developed character, perhaps because Shelley describes his experiences from “birth” on. We see how his awareness of the world develops: his initial innocence and wonder at the beauty of nature, his essential goodness before he’s broken by the cruelty of humanity. He says, “I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend.” Shelley’s dialogue between him and Victor is incredibly rich with philosophical ideas and tension! It made my job as a novelist far easier. As for Caroline, Elizabeth, and Justine, they are idealized versions of feminine ideals—projections of Victor’s narcissistic eye, if you will. Victor perceives Caroline as his selfless mother, Elizabeth his perfect mate, and Justine the devoted servant

To research UNNATURAL CREATURES, Waldherr traveled to the sites mentioned in Frankenstein including Mont Blanc and the Mer de Glace (pictured above), where Victor Frankenstein has a fateful encounter with his monster.

I found interesting themes in your book such as the fear of birth, which of course in that era could kill women. Do you think Shelley herself was consciously developing that as a theme? Her own mother died because of childbirth.

Shelley doesn’t overtly mention the fear of birth in Frankenstein, but I’m sure it must have been on her mind, between her mother’s death and her own personal experiences—I think Shelley was only 16 when she gave birth for the first time. She specifically writes that Caroline, Victor’s mother, “had much desired to have a daughter, but [Victor] continued their single offspring” and that there were seven years between the birth of Victor and his younger brother, Ernest. That led me to conclude Caroline must have suffered some infertility and miscarriages along the way.

Shelley’s book was very transgressive in fundamental ways, and I’ve always found the Victor/Elizabeth relationship incestuous in that they were brought up as brother and sister. I loved how you opened it up from her point of view. How easy was that to do?

It was hugely challenging, to be honest. Elizabeth is essentially Victor’s projection—she’s too perfect, too beautiful. Even later, after tragedy has struck the Frankenstein family, Victor describes Elizabeth as “thinner and had lost much of that heavenly vivacity that had before charmed me; but her gentleness and soft looks of compassion made her a more fit companion for one blasted and miserable as I was.” She’s still his ideal mate, if you will—who cares she’s suffering?

It took me several drafts to dig deeper into Elizabeth as someone separate from Victor, to find her shadow. I reread all editions of Frankenstein in search of clues. For example, in Shelley’s 1816 manuscript, Elizabeth’s involvement with art is mentioned, so I made her an artist in UNNATURAL CREATURES.

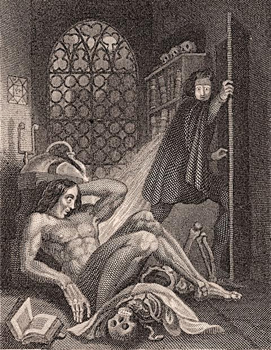

While writing UNNATURAL CREATURES, Waldherr read all editions of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein multiple times. However, she primarily drew from the 1831 edition, which features this frontispiece drawn by Theodor von Holst.

There is a wonderful mood through the novel, one of sensual longing mixed with dread. Would you describe that as a gothic feeling? How did you sustain it?

I’m thrilled you liked the mood—and it is definitely intended as a gothic feeling. Whenever I give presentations about gothic novels, I joke that the gothic is comprised of what I call the “Two D’s”: Dread and Desire. Tension arises because characters desire what they most dread, which creates internal conflict—and gothics are often about displaced internal conflict. As for creating that eerie mood, I think my background as a visual artist helps when it comes to writing description and creating atmosphere, which are such important elements in gothic novels.

Was it a challenge writing the character of Frankenstein’s Creature? I loved the choices you made there!

Believe it or not, the Creature was the easiest character to write, probably because Shelley’s descriptions of him are incomparably vivid. He’s so articulate too. I ended up adapting his words fairly directly from Frankenstein—why mess with something that’s already perfect?

On a related note, I have to say that Barrie Kreinik’s vocalization of the Creature in the audiobook of UNNATURAL CREATURES is brilliant. I had chills up my spine the first time I heard it. Barrie makes him sound like the incarnate of a nightmare.

Is this the scariest novel you’ve ever written?

Definitely! Though my debut novel The Lost History of Dreams was also a gothic, it was about ghosts and loss rather than monsters and terror. I’m a very sensitive person; while writing UNNATURAL CREATURES, I had to step back a few times to catch my breath. There are two scenes that were really painful to write, one involving a child in peril and another that’s an execution. (I have to thank my agent for pushing me to go darker on those scenes!) That said, I adored writing some of the creepier elements that are threaded throughout.

You know a great deal about tarot and the supernatural. Did these come into play in this book?

I’ve been working with the tarot for over 30 years—it’s such a fabulous tool for storytelling! I even teach a Tarot for Fiction Writers workshop that includes exercises for deepening backstories and character arcs. These came in handy while I was writing UNNATURAL CREATURES. Whenever I got stuck, I’d go pull some cards.

I really like how you wove in the politics of the time. Europe was in extreme turmoil in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Do you think that’s overlooked when people read the original book or watch the many film and TV adaptations?

I do think the historical elements of Frankenstein often get overlooked; off the top of my head, the only novel I can recall directly mentioning the political turmoil in Geneva is Theodore Roszak’s The Memoirs of Elizabeth Frankenstein, which is very different from UNNATURAL CREATURES. As for myself, I’ve always been struck by the plot point of Justine’s aunt in Chêne, who serves as the maid’s alibi in Frankenstein. Why didn’t the aunt testify at Justine’s trial? Why does Justine mention Chêne, a small village south of Geneva, so specifically? When I learned Chêne had been forced under French rule in 1792, I experienced a “Eureka!” moment.

In Frankenstein, Belle Rive, which lies three miles outside Geneva, is the location of the Frankenstein family’s country home. Photo credit: Kris Waldherr

From there, I was stunned to learn Geneva experienced several revolutions of its own, and in 1794 executed 11 syndics—judges who served as Geneva’s ruling aristocracy—in Plainpalais, the same place where Justine meets a tragic fate. (In Frankenstein, Victor’s father is identified as a syndic.) Mary Shelley’s travel narrative History of a Six Weeks’ Tour, which was published the year before Frankenstein’s 1818 publication, mentions the execution of the syndics in Plainpalais—Shelley was definitely aware of it.

Finally, the University of Ingolstadt, where Victor creates his monster, was considered a center for revolutionary ideas and unrest. As I charted my way through the history coinciding with Shelley’s novel, I’m particularly indebted to Frank V. Randel’s paper “The Political Geography of Horror in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein” and Janet Polasky’s book Revolutions Without Borders: The Call to Liberty in the Atlantic World. Both are fascinating reads!

What is your next book project?

Something far less complicated to write, hopefully! I have a few projects underway, one which is a long-aborning gothic retelling of a Tennyson poem, and another that’s a historical romance. However, the novel I’m most excited about is set in 19th century Venice. It’s currently more fantastical than eerie, but I suspect that will shift as I write. Plus, I’d love a reason to travel again to Venice.

- Up Close: Kris Waldherr - September 30, 2022

- Up Close: Wendy Webb by Nancy Bilyeau - October 31, 2018

- Between the Lines: J. D. Barker - September 30, 2018