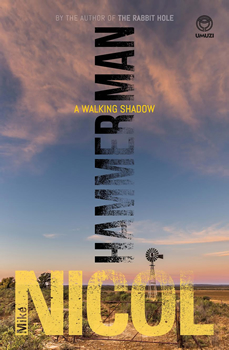

Africa Scene: Mike Nicol

Nicol Hammers Home a New Hit

HAMMERMAN is the latest blockbuster from one of South Africa’s most talented thriller writers. Mike Nicol is a novelist and stylist, and every one of his books is a treat. HAMMERMAN is no exception.

One evening in February 1986, a man assassinated the Swedish prime minister, Olaf Palme, shooting him outside a cinema. No one has ever been convicted of the crime, and at the time there were rumors that South Africa was involved in some way because of Palme’s outspoken opposition to apartheid and his pro-sanctions stance. In HAMMERMAN, Nicol has taken that idea, and explored how the ripples from that event might spread to the present day.

Early in the book, we discover that AJ, a colonel in the South African Police Service, has a double life that makes him an asset as well as a threat. When he is murdered execution-style, his distraught wife hires PI Fish Pescado to find out the real story. That takes him on a dangerous trail that leads to a farm in the Moordenaars (Murderers) Karoo desert and a man who might, or might not, have been behind the assassination.

Here, Nicol chats to The Big Thrill about his latest Fish and Vicki thriller.

The premise of HAMMERMAN is that the assassin of Olaf Palme was a South African working for BOSS, the infamous apartheid-era Bureau of State Security. What drew you to the idea of using that in a Fish and Vicki thriller?

The thing about many crime novels, certainly the ones I most value, is that they are also political novels. They reveal a country’s history, politics, society. In an endnote in James Ellroy’s novel Perfidia, he writes about his fiction being a “novelistic history.” Which is what much crime fiction is all about. With my Fish and Vicki series, I started with Of Cops & Robbers where the story hung on a number of apartheid hit squad raids into neighbouring territories and the mysterious killing of the Nationalist Party politician Dr Robert Smit and his wife Jean-Cora in 1977. No one was ever found guilty of those murders. Then in Agents of the State, I returned to the assassination of Dulcie September in Paris in 1987 (first referenced in Of Cops & Robbers). She ran a branch of the African National Congress in Paris, and it remains a moot point as to whether she was killed by an ANC hitman or someone commissioned by the French secret service. The next two novels in the series, Sleeper and The Rabbit Hole, despite mentions of past crimes, are more focused on the current looting of the state by members of the ruling ANC. With HAMMERMAN, I wanted to once again link the past to the present. I have long been fascinated by the mystery of the Palme assassination, and as it seems that BOSS agents were seriously thinking of killing him (they even had Hammer as the code name for the operation), I thought, why not bleed it all into the novel?

After she’s attacked at the end of The Rabbit Hole, Vicki is left in a coma, and no one knows if she’ll recover. Fish carries on but is also damaged, even giving up surfing. He holds a conversation with her in his head. Sometimes it seems he extrapolates her natural reactions, but on occasion she seems to actually supply him with ideas and even information. Did you intend this “communication” to be more than Fish’s imaginings in response to loneliness and grief?

There were a number of things at work here. In a way Vicki, even though she’s not dead, plays the part of a ghost, like Hamlet’s father or Banquo in Macbeth or the teenager in the teen-thriller The Invisible. In cold, academic terms, she’s a literary device and comments on what is happening and does supply Fish with information and ideas. Of course, mostly, he is keeping her “alive” in his head. I have come to believe that there was another influence here. Three years ago, my stepdaughter died, and I soon realized that I often had conversations with her in my head. And still do, actually. We’d had a close relationship, and although obviously, she wasn’t talking back, this was one way of dealing with the grief of being without her. At some level, I reckon this led to the “discussions” between Fish and the unconscious Vicki.

AJ is a complicated character. He was a hitman in BOSS days and is persuaded to revert to that role in post-apartheid South Africa. Yet he’s a loyal friend, gentle husband, and loving father. He’s also a courageous and successful colonel in the new police. While everyone compartmentalizes their lives to some extent, would such an extreme division—and behavior—require an intrinsically unbalanced personality?

Over the last couple of years, I’ve experienced the behavior of a sociopath and been quite close to the story of another sociopath who ensnared her partner for two years before he was able to break free. This experience and observation went into forming AJ’s character as sociopaths are adroit at presenting a face to meet the faces that they meet, to borrow from T S Eliot. Yes, we all compartmentalize our lives (some of us extremely successfully when you consider the politicians and civil servants who are also thieves), but sociopaths are the experts: They can be charming; they can be deadly. So yes, I saw AJ as being one of those fantasists from the BOSS era who could be both killer and loving father, husband, brother.

AJ’s wife, Sonja, hires Fish to look into the circumstances of AJ’s death. The official version is a gang hit, but she doesn’t believe that, and she’s right. She’s totally unaware of AJ’s past activities and refuses to believe the information Fish starts to dig up. But when a retired Belgian spy master gets involved, the tables turn. Is Sonja the key to what finally happens in the story?

Indeed. Without Sonja, there is no story. She puts everything in motion. What strikes me is that so often in younger people I encounter incredulity about what happened in the past, and a past that wasn’t that long ago. A past that many of us lived through. At first, Sonja represents that incredulity. How could things have ever been like that? Then, as more evidence comes to light, she has to face the past and with it the consequences of matters that are still not resolved.

We know almost from the start of the book what happened to the Swedish prime minister and AJ’s role in that, but Fish needs to follow the trail. Were you tempted to write the book as a murder mystery where Fish would have to find out why AJ was killed as well as who was responsible?

Not really. I’m not—and wasn’t—that interested in writing a murder mystery. My fascination with stories and plots is from the perspective of, okay, this has happened, what’s going to happen next? And again, with HAMMERMAN, it was about how the past would influence the present. So although it was pretty clear early on what AJ’s role was, his story was more about how he’d become involved in the Palme assassination and how that killing could be used to subvert politics in the here and now.

As usual, The Voice is pulling the strings behind the scenes with her agent, Mart Velaze, one of her puppets. But when she blackmails AJ, she sets off a chain reaction that even she can’t control. Her operation is secret even from the other spies in the Aviary. Does that give her the freedom to operate as she sees fit, but no Plan B in the event of failure?

Shortly before I started writing HAMMERMAN, I read The New Spymasters by the British broadcaster and investigative journalist Stephen Grey. About two thirds of the way through the book, he discusses the aberrant behavior of spymasters. If they are in an “isolated environment” (his words)—as is the Voice—they can go rogue. To quote him: “Apparently, if their activities are kept secret, usually ordinary and decent people will do irrational and indecent things. Or as one British intelligence officer put it crudely, ‘intelligence agencies whose operations are pursued without strict outside scrutiny invariably fuck up in the end.’” Those two sentences gave me the other side of this story. In the Voice’s world, there is no Plan B. Throughout the series, she has been the voice of decency, she is the righter of wrongs (albeit sometimes by nasty means), and, once again she is motivated to counter what she perceives as a danger. But then she lives in a morally ambiguous universe.

We’ll miss Fish and Vicki and Janet. At what point, and why, did you decide that HAMMERMAN would be the last in the Fish and Vicki series?

Over the last 15 years, I’ve written two different series in the crime fiction genre. The first series was from the point of view of guys working in private security with a background in gun-running for the ANC during the apartheid years. The Fish and Vicki series was an attempt to use past atrocities to frame the ANC’s corruption since they came to power. It is woefully ironic that this liberation organization only really managed to destroy the South African state once they were in power. It’s axiomatic that in the apartheid years, the South African Police Force (now the police service), was a powerful institution in the control of the state. Today that institution, charged as it is with keeping law and order, has become synonymous with organized crime. Obviously, there are still good people in the police, just as there were in days gone by, but it seems to me that for my crime fiction project, I should now turn to the cop novel. I have avoided using cops as the main protagonists thus far because cops always seemed to be part of an invading army. But they can no longer be avoided.

So what’s next?

That above mentioned cop novel. Not a police procedural. A novel where cops are the main characters. And, oh, yes, Janet will be back.

- Out of Africa: Annamaria Alfieri by Michael Sears - November 19, 2024

- Africa Scene: Abi Daré by Michael Sears - October 4, 2024

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024