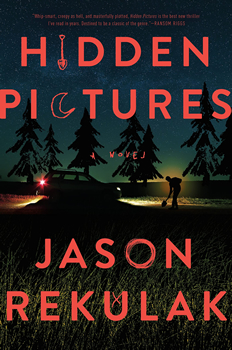

Up Close: Jason Rekulak

A Ghost Story with a Body Count

After more than 20 years in the publishing industry, Jason Rekulak knows a good idea when he has one.

During his lengthy stint as the publisher of Philadelphia’s Quirk Books, the indie house behind such hits as William Shakespeare’s Star Wars and The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires, Rekulak’s off-the-cuff ideas launched bestselling franchises—and sometimes even entire categories. When a screenwriter and vintage photo collector approached Rekulak about publishing a book of antique photographs, Rekulak urged him to write a novel about an orphanage inspired by the children in the photos. The collector was Ransom Riggs, and the result was Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children. When Rekulak wondered what would happen if someone turned a public-domain classic into a gory horror story, he hired Seth Grahame-Smith to write Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, kicking off a wave of mashup books.

In the six-year period from 2009 to 2015, as many as 10 New York Times bestsellers could be traced back to Rekulak, who either acquired them or conceived the idea and found the right author to execute them. So when he was walking down a Philadelphia street and nearly the entire plot of HIDDEN PICTURES came to him at once, Rekulak trusted his instincts enough to immediately duck into a coffee shop to write it all down.

The story concerns a young woman, recovering from drug addiction and a family tragedy, who accepts a too-good-to-be-true summer job nannying for an affluent couple and their sweet five-year-old son. Not long after Mallory Quinn moves into Ted and Caroline Maxwell’s newly restored guest cottage, young Teddy begins to exhibit troubling behavior, including drawing pictures that seem to depict a woman’s lifeless body being dragged through the woods. Mallory also learns that her new home comes with a grim legacy: in the 1940s, a local artist disappeared from the cottage, leaving behind nothing but blood-spattered walls and an abiding mystery, prompting some locals to call the little structure “the Devil House.” As Teddy’s drawings become more disturbing, Mallory enlists the help of a local landscaper and the eccentric psychic next door to finally solve the mystery and free the boy from whatever otherworldly force seems to have him in its grip.

In his first-ever interview with The Big Thrill, Rekulak—his name is Ukrainian, and it’s pronounced “ruh-COOL-ick,” if you’re wondering—talks about finding his “lane” as a novelist, riffing on one of the most famous ghost stories ever written, and working with a pair of talented illustrators to produce the relentlessly paced, immensely entertaining HIDDEN PICTURES.

Your first novel, The Impossible Fortress, was inspired by your childhood experiences. Where did HIDDEN PICTURES come from? If you tell me this one was also inspired by your formative years, this interview is going to be wild.

I wanted to write a novel with illustrations for an adult audience. I’ve been interested in the possibilities of illustrated fiction for a long time. I’m sure some readers dismiss “novels with pictures” as childish or gimmicky, but I think they’re an interesting way to engage 21st century attention spans. After all, you’re probably reading this interview on a screen, and the text is probably bracketed by all kinds of colorful compelling imagery. What if a novel offered some of the same visual excitement? I guess I just love print books, and some of the most beautiful books ever printed have been lavishly illustrated.

In my previous life (as publisher of an indie press, Quirk Books) I published illustrated novels like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (with faux 19th century engravings) and Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children (with dozens of haunting vintage photographs). And after working on these books and several others, I had this goal of writing an illustrated novel of my own.

Sometime in 2019, I started talking to a pair of illustrators, Will Staehle and Doogie Horner, about collaborating on some kind of book-length project. They’re both wildly creative guys, and I enjoyed spending time with them; I knew they would be the perfect partners. It took me a long time to figure out the right story for our collaboration. I considered a lot of different ideas before arriving at the story of a babysitter and a five-year-old boy who likes to draw.

These books are obviously very different; one’s a coming-of-age story set against the backdrop of computer gaming in the ’80s, and the other is a contemporary supernatural thriller. Authors talk a lot about branding. (Well, some do.) How would you describe the Jason Rekulak brand of fiction?

I see what you’re getting at—I really do have a terrible brand! But you’re right—the publishing industry loves authors who “stay in their lane”—authors who write the same kinds of books for the same readers, over and over. Legal thrillers, space operas, vampire erotica, etc. It’s the fastest and easiest way to build an author’s fan base.

My problem after selling The Impossible Fortress was: Well, how many more coming-of-age novels did I want to write? One seemed plenty. I couldn’t imagine writing another. I had to change lanes.

So I thought a lot about what I liked to read, and I realized that most of my favorite authors are working in suspense, so that’s where I went. And if I have to stay in this lane for the rest of my career, I’ll be pretty happy. It’s a big lane with lots of room for innovation. I’m excited to be here!

The Impossible Fortress was your debut under your own name, but you wrote about a dozen books for Quirk under various pen names, and you conceived many more that you farmed out to other writers. I get the impression you have more ideas than you can possibly find time to write. What made you decide HIDDEN PICTURES would be your second novel?

I have lots of ideas, but most are not well-suited for novels, because most of the ideas are just premises, and a premise is not the same thing as a story. Nine times out of ten, I will start exploring a premise, testing its potential, drafting 30 or 40 sample pages, and the story just fizzles out.

But with HIDDEN PICTURES, I discovered the premise and the entire story at the same time. I was walking down my street in Philadelphia when everything hit me like a ton of bricks. I ran into the closest coffee shop and wrote three pages of notes, and everything was pretty much there. I still don’t really know how it happened. I wish I could will it to happen again; I would save myself a lot of time and false starts!

Do you think of HIDDEN PICTURES as a horror novel? Why or why not?

It’s definitely a ghost story with a body count—that sounds like a horror novel, right? But maybe it’s more apt to call it a supernatural thriller.

I’m not sure it’s even possible to discuss a story about a nanny confronted with possibly supernatural forces without talking about The Turn of the Screw, and your book even includes a pretty blatant nod in the form of a character name. In what ways is HIDDEN PICTURES a response to Henry James’s story?

Writers have been riffing on Turn of the Screw for 150 years. That story is in our collective storytelling DNA. Anytime a young woman travels to a new home to care for small children, and she starts hearing bumps in the night, and everyone else thinks she’s crazy—well, that story is operating in the shadow of The Turn of the Screw. Since I knew my book had a very unusual form (re: the illustrated clues), I found it helpful to anchor the narrative in a familiar tradition.

I understand The Impossible Fortress began as journal entries that eventually became the framework of a novel. HIDDEN PICTURES must have been a very different process. How did it come together for you?

Writing this book was pretty straightforward. As I said, I had a good grip on the story at the beginning. I knew all of the big twists right up front, so the biggest complication was incorporating the 50+ illustrations in interesting and surprising ways. Some of them needed to convey narrative information or clues. Others just needed to be creepy. So I would give a very broad description of what I needed to my illustrators—I tried to give them as much creative leeway as possible—and invariably they would return with an illustration that was better than anything I’d imagined. In fact, I usually went back and revised my text after they submitted an illustration, to incorporate details or ideas they’d contributed.

All told, the book came together in about a year, which is really fast. It helped that we were all in lockdown, so we all had a little extra time on our hands.

I can’t imagine how many submissions you must have read during your time at Quirk. How did evaluating all those books from the perspective of a publisher affect you as a writer?

I learned a lot about how books are sold. As a publisher, you are constantly pitching books. You’re pitching books to your staff, to your sales reps, to booksellers, to your friends and neighbors. And in my experience, the worst kind of pitch is: “Oh, it’s hard to describe, you just have to read it!” That is NOT a pitch! Booksellers are wading through thousands of new titles every year; you can’t expect these folks to read everything.

So when I’m considering my writing projects, I always think about how the book will be sold. What’s the audience for a book? Who buys it? How does it rise above the thousands of new titles releasing next year? Maybe this makes me sound crass or cynical, but I think I’m just being realistic.

On that note, are you a publisher who became a writer, or a writer who became a publisher?

Definitely a writer who became a publisher. I’ve been writing since my junior year of college. Every day, an hour or two a day. Even when I was working at a full-time job, I always carved out time at lunch (or early in the morning, or very late at night). And always at the expense of other things: I sacrificed a lot of time that I could have spent with friends. I missed a lot of good prestige TV shows. I remained unpublished for a long time, and there were many years when I wondered “Why the hell am I still doing this?” But I kept doing it, anyway. And (thank God) my wife never questioned it!

Was it hard to shift from a publisher’s mindset to an author’s?

A little bit. As a publisher, I could control every aspect of a book’s publication—but as an author, I have to trust my publisher to make all the right decisions. (Fortunately, I have a great publisher!) For example, with HIDDEN PICTURES, I was very concerned about how the illustrations would be printed; I had all kinds of concerns about ink coverage and the interior paper stock and even the interior paper color (cream stock versus white stock), and sometimes I had to remind myself to keep my mouth shut and just let everyone on the team do their jobs.

In one way or another, you’re behind some pretty big properties and authors. You convinced Ransom Riggs to write the Miss Peregrine series, and you launched Grady Hendrix’s fiction career with Horrorstör, Seth Grahame-Smith’s with Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, and Ben H. Winters’s with The Last Policeman. What’s your proudest professional accomplishment so far?

You just summed it up right there. Those authors are all very busy writing bestsellers and producing Hollywood movies and winning literary prizes, and I am proud that I played a role at the start of their careers, when they were still mostly unpublished and unknown. And I’m really proud of everything they’ve achieved (and continue to achieve). Gosh, you’re making me miss my old job!

Can you tell me anything about what you’re working on now?

Not yet, sorry. I’m exploring a really great premise, but I’m not completely sure it’s a great story.

- AudioFile Spotlight: March Mystery and Suspense Audiobooks - March 17, 2025

- Africa Scene: Shadow City by Natalie Conyer - March 17, 2025

- The Ballad of the Great Value Boys by Ken Harris - February 15, 2025