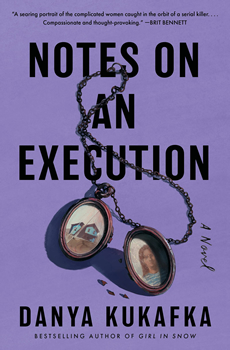

Up Close: Danya Kukafka

A Novel for the Women Who Survive

By K.L. Romo

By K.L. Romo

Bestselling author and literary agent Danya Kukafka was weary of society’s compulsive obsession with male serial killers—the focus should be on the victims and their families, she believes.

As such, NOTES ON AN EXECUTION is not the serial killer’s story. In her author’s notes, Kukafka writes that the novel “was born from a desire to dissect this exhausted narrative, society’s fascination with serial killers. We rarely talk about what we lose when women die. The book belongs, instead, to the women irrevocably changed by his actions. This is a book for women who survive.”

Serial killer Ansel Packer, inmate 999631, has only 12 hours to live. Although the story begins with the countdown to his execution, the real focus of the novel is on the women involved in his life, and the lives of his victims.

In 1973, Ansel’s mother, Lavender, is only 17 when she gives birth to him in the barn at an isolated farm. Her abusive husband is unforgiving in his demands that she and Ansel show the gratitude he deserves. Upon the birth of her second son, Lavender’s desperation to escape her life takes precedence above all else, even her sons. She must save herself, or she will perish.

Saffron (Saffy) Singh first meets Ansel at Ms. Gemma’s house in 1984, where they are both foster kids. Saffy’s infatuation with Ansel comes to an end when she discovers his fascination with violence and death. Ansel’s cruelty toward her leaves Saffy damaged, reliving the nightmare again and again.

Hazel Fisk meets Ansel in 1991 when her twin sister, Jenny, brings him home for Christmas. Until Jenny met Ansel, the girls were inseparable. Now that he’s in their lives, his presence threatens to tear their family apart.

In 1999, the buried remains of three girls who disappeared in 1990 are found, and Saffy is the NY State Police investigator assigned to the case. She can’t help but consider what the dead girls’ lives would have been if they’d lived. Saffy will catch the Girly Killer.

Ansel believes that “there is good and there is evil, and the contradiction lives in everyone. The good is simply the stuff worth remembering.”

Kukafka writes the narrative in chapters alternating between Ansel, written in a detached second person, and the women, writing in third person. Her literary prose throughout the book is almost lyrical, beautiful in its metaphors and rich in imagery.

Here, she talks with The Big Thrill about what inspired the novel, her thoughts about how society’s focus should be on the victims, and the message she’d like readers to take away from the book.

What was the inspiration for NOTES ON AN EXECUTION?

I’ve always loved reading crime novels and mysteries, and I grew up watching network crime television (Law & Order SVU, CSI Miami, and Criminal Minds were my favorites). I noticed that stories of murder often take on the same repetitive structure—the body is found, detectives hunt the killer, justice is served. But I was curious about the bigger human questions that run beneath these narratives. I suspect the nuances found within stories of violent crime are much more complicated than popular media usually allows, and I wanted to write a novel that lives in this undercurrent, that tells the deeper and darker truth of what happens after violence.

Can you expand on your premise that society focuses on the serial killers themselves and not on the victims?

We grow up hearing their names—Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, Jeffrey Dahmer, Charles Manson. Most of these men committed their crimes decades ago, but we’re still telling their stories. We rarely hear the names of their victims, much less the names of their mothers or wives or sisters.

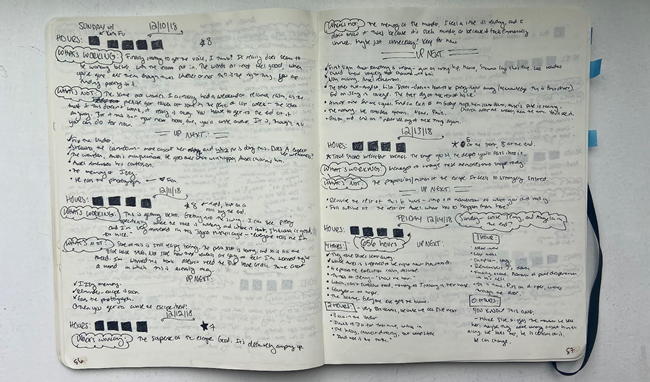

“When I started writing NOTES ON AN EXECUTION, I also started keeping a process journal,” Kukafka says. “Every session, I did some reflecting on what was good, what wasn’t, and what needed to come next. I kept sections open in the back for inspirational quotes, research, and free writing. Am I completely insane?? 1000% yes. But little by little, the hours added up and the story took shape.”

You also note that we don’t focus enough on what is lost when a woman is murdered; what might she have done in her life that she never had the chance to do.

This novel made me think about the concept of the multiverse—if we’d made just one choice differently, where would we be now? When you apply this question to the after-effects of murder, it quickly becomes devastating. When one man makes a bad choice, women lose absolutely everything. The serial killer makes the decision to commit murder in seconds, but the infinite possibilities for the futures of the women he kills are forever ripped away. I wanted to explore this imbalance, to show its cruelty.

Can you comment more on the theme of perception? How we see each other and ourselves can differ from how others see us.

Kukafka spent the first weekend of 2022 signing 1,200 tip-in sheets for Waterstones UK. The sheets will be bound into signed special editions of NOTES ON AN EXECUTION.

I love this theme. This question was important to my first novel, Girl in Snow, and I think there are still reverberations of it here. The images we have of ourselves are often thrown into stark relief based on circumstance—who we want to be versus who we are. It’s a paradox I’m always grappling with.

Can you comment more on Ansel’s “theory” that people are both good and evil, and that there are many “alternate universes” that could have existed had he made different choices?

Ansel’s “theory” addresses both of your questions above—he wants to believe that he’s smart, that he’s different, that he’s not your average killer. That there’s more to him than the crimes he committed. But at the end of the day, he made the choices he made, and alternate universes are irrelevant. We just have this one world, this one reality.

What are the messages you’d like readers to take away from the book?

I hope this novel makes readers think about how we consume stories of bad men. How do we punish them, and how do we glorify them? How might we change public perception of violent crime, to make space for the people it affects, rather than putting murderers on pedestals? I like to say that this is a novel for the women who survive.

Can you give us a hint about your next novel?

I would give you a hint if I had one! I’m well into drafting the next novel, but if writing this story taught me anything, it’s that the concept of a book can change drastically over the course of its evolution. My next novel will probably be similarly dark, and I think it will involve questions about climate change. But ask me again in a few years…

Being such an accomplished author at such a young age, what advice can you give other writers?

The process is the point. This is the mantra I’ve been trying to ingrain in my own head for years. Publication is a completely different world from the process of writing a book—and the process of writing is the purpose of the whole endeavor. If you can accept that writing a novel happens for the sake of it, for yourself and for the story, rather than for any external goal or ideal, you will be a much better and much happier writer.

Tell us something about yourself your fans might not already know.

I make my own pickles, avidly and obsessively. I’m a big fan of pinball—I used to play on a competitive team, and my favorite machine is the old-school Medieval Madness. I learned how to knit during the pandemic, and now I work part-time at a yarn shop for fun. And most importantly, I work as a literary agent with Trellis Literary Management. You can read more about my wish list and query guidelines on the Trellis website! If you’re writing crime, particularly in the BIPOC, literary, or experimental spaces, I would love to hear from you.

- The Big Thrill Recommends: ONE BIG HAPPY FAMILY by Jamie Day - September 16, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: ONLY ONE SURVIVES (Video) by Hannah Mary McKinnon - July 30, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: WHAT YOU LEAVE BEHIND by Wanda M. Morris - June 27, 2024