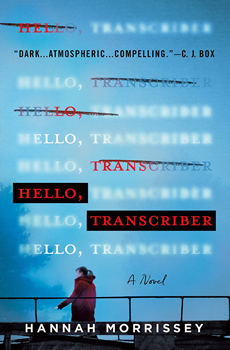

BookTrib Spotlight: Hannah Morrissey

A Police Transcriber Finds the Real Thing Close to Home

“This job is violent and graphic in nature. You’ll have to listen to accounts of things that are…traumatic…to say the least. It’s not for everyone.”

“Good thing I’m not everyone.”

In Hannah Morrissey’s HELLO, TRANSCRIBER, Hazel Greenlee, 26, has just been hired as a police transcriber for Black Harbor, Wisconsin, the state’s most crime-ridden city. The shifts are at night, ten hours each, Sunday through Thursday, typing dictated reports left for her by the detectives.

The other transcriber tries to warn her, “People with normal jobs don’t get it. If I had to count how many friends the job cost me over the years…we’d be here all morning,” but for Hannah, though the stories are indeed brutal, the work is kind of peaceful: In less than a week, “my sense of hearing seems heightened. I am starting to read voices like Braille, the smoothness or roughness of them, the pauses.”

She has need for the peace. She ran from her small hometown three hours north in the wake of a trauma. Her marriage to her high school boyfriend has become increasingly shaky. The local suicide spot, a railroad bridge over a black river, seems to call to her.

And then one night, her next-door neighbor, Sam, appears at her office window and scrawls with a finger in the frost, I hid a body. The finger he uses is not his own; it has been broken off below the first knuckle.

The body is that of a nine-year-old boy, and he has apparently been killed by a notorious local drug dealer known as “Candy Man.” Through her headset, she hears all the details of the investigation, finds herself sucked in by its twists and turns, and then finally crosses the line, venturing into the investigation itself, which is led by a brooding detective named Nikolai Kole.

She knows what she’s doing is wrong. She knows her attraction to Kole is wrong. She knows he is hiding secrets, just as she is, just as everyone in Black Harbor seems to be: “No one in this city is who they say they are, a truth that becomes more and more apparent every day.”

And she knows, as more bodies emerge, that there is something desperately wrong with the case—but just how wrong she could not possibly imagine until it’s too late. No one comes willingly to Black Harbor, she’s told early on. And no one leaves by their own volition. The only way out is down.

HELLO, TRANSCRIBER is a dazzling debut novel, dark, chilling, filled with extraordinary atmosphere and power, at once a psychological thriller, police procedural, and haunting character study.

How far would you go to escape your life?

Hannah Morrissey knows what she’s talking about—she herself spent three and a half years as a police transcriber in Racine, Wisconsin:

“The idea for HELLO, TRANSCRIBER came to me while I was working as a police transcriber on the night shift. It was this narrow terrarium-like office. The whole outward-facing wall was a window, and I would stare out as I listened to detectives all night long tell me the goings-on of the city—the dangers that lurked just beyond my thin sheet of glass—and I thought…that’s pretty cool.

“It was an unusual job with unusual elements, such as knowing people by voice instead of face, living an opposite schedule than most people, and being a secret-keeper.

“So I started writing. Just noting my observations at first and then dreaming up characters. Writing wasn’t a novel concept for me; I’d gone to college for creative writing, and I’d written— and shelved—four other manuscripts at that point. I had a fantasy, a YA fantasy, a YA coming-of-age, and a dystopian novel all dying on my hard drive. Despite all the words and characters and plots I’d explored, there was one thing I was perpetually missing: voice.

“Literary fiction is a genre I love: the descriptiveness, the multi-layered plot and textured characters, the beautiful language. I’d always wanted to write something that could have a commercial plot and literary prose. With that mission in mind, I returned to the classic advice of ‘write what you know,’ and suddenly, what I knew was crime. Fortunately for me, it’s a pretty popular genre.

“What brought me into the transcriber job was really the listing itself. I think a lot of us—especially thriller addicts, mystery lovers, and crime junkies—are intrigued by the behind-the-scenes of police work. Plus, my uncle was a sheriff’s lieutenant at the time (now retired) so I grew up being fascinated by his stories. When I read the job description, I couldn’t believe that typing reports for police investigators was a real job. The requirements were all things I knew I could do: type at least 55 wpm, agree to swear an oath of confidentiality, be content to work alone, and not be emotionally affected by violent or traumatic reports. I felt as though the job had been made for me. So I applied, got invited to take the typing test, crushed it, and I was awarded the job out of a pool of over 500 applicants.

“I had regular contact with the investigators, and I’m friends with many of them to this day. To be honest, it depended on people’s schedules and how much interaction they wanted to have with a transcriber. I think I felt like I had more contact with people than I did, because I was listening to them all the time. In the book, Hazel mentions preferring one-sided conversations, and I got to be that way, too. Just put the headset on and listen to someone tell you a story and type every word they say.

“Working on the night shift, I caught a lot of second-shift investigators’ reports and Special Investigations Unit (SIU). I loved those. They worked with confidential informants to make controlled purchases, conducted search warrants…the exciting stuff.

“The most surprising thing that happened to me while working as a transcriber was…falling in love. That came out of nowhere. I don’t know if I’d say it was love at first listen—maybe it was—but there was definitely something that happened when I heard him for the first time. He was dictating a report for a search warrant he’d been lead on, and his narrative was so organized, his commas were in all the right places, and he knew the difference between a colon and a semicolon—I was smitten. When we finally met in person (turns out he’d been conducting his own investigation on me), it was a done deal.

“Another surprising thing was the sheer amount of crime that went on in this city I now lived in. I knew the crime rate was much higher than anywhere else I’d ever been, but I had no idea what an epidemic there was of heroin and cocaine until I started working at the police department, not to mention the murders that happened just a few houses down from mine.

“There was a case about a confidential informant being stabbed to death, there was a drug overdose in the apartments across the street from the police department, and I remember typing a report about a body found floating in the river, and once I had a bunch of elements and observations written down, that was really the crux that pulled everything together, this idea that there could be a place so terrible that people jump from a bridge to escape it. I bet I think about that case almost every day—it haunts me a little—just seeing the bleached white skin and the blurred, bluish tattoos. When I first saw the photos, I thought he was wearing a white T-shirt, but it was his skin that had been bleached white. And I started thinking, what kind of place makes someone do this? Welcome to Black Harbor.”

Hazel has a lot of very distinctive characteristics—she’s escaped from a small northern town; she has tattoos, a creative writing degree, a later job as an ad copywriter. She also has a habit of typing out words on her arm or lap, and carefully stores up new words she reads or hears for later use. How much of her comes from Morrissey herself?

“There’s quite a bit that Hazel and I share in common. Writing is a process of deconstructing and reconstructing, stripping something down to its core elements and then building it up and reshaping it. At least, that’s how I look at it. The elements of myself that I kept were ones that I thought would help drive the story I wanted to tell and shape the character I wanted to write, which was someone who felt out of place. I was really inspired by a neologism from the Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows by John Koenig: monochopsis. It means the subtle yet persistent feeling of being out of place, and not being able to recognize that it is, in fact, exactly where you belong.

“When I moved to Racine, having grown up on a farm in an unincorporated town, it was a shock to my system. Everything was so different, and I think one of the most surprising things to me was that people were fascinated—for better or for worse—over the way I talked. Whenever I spoke, they were instantly curious about where I was from (I got a lot of guesses of Canada). I held out my ‘o’s’ too long—or so I’ve been told—and I wasn’t familiar with the vernacular or the slang. And when you don’t ‘speak the language,’ so to say, it really adds to this feeling of not belonging somewhere.

“The finger-tapping is something I used to do. I don’t remember quite when I stopped, but I remember I started doing it around third grade, when we first took keyboarding class. My friend always had the best typing score, and I wanted to beat him, so I would practice in my off-time listening and mime-typing what people said. It’s funny because I’m a triplet, and I asked my sisters about it once, and they do the same thing. So maybe it’s a weird triplet thing. Or maybe they both had really wanted to beat him, too.

“I do store up words for later use. That might be why I’m such a slow reader, because I keep a vocabulary list in every book I read. Every time I come across a new word, I write it down along with its definition. If I write it down, I’m more likely to remember it. I can probably even tell you which words I learned from which books. For instance, I learned ‘adumbration’ from My Darling Absolutely, and ‘sibilant’ from The Heart-Shaped Box.

“The spruce tree tattoo on the back of Hazel’s arm is a nod to my hometown, and it gives her the unsettling feeling that she has to hide it in order to feel accepted by her in-laws. I know tattoos are self-inflicted—they’re not like a birthmark or a scar—but they’re still part of you. I love tattoos. I love how mainstream they’ve become, and I think they’re a great form of self-expression. Especially for an introvert like Hazel who is more apt to listen than to speak. They’re telling, too, because if someone’s committed to having this image on their skin for the rest of their life, it must be meaningful. My protagonist in my next book, Morgan, has a two-headed snake tattoo, and I’ll be really curious to see if readers decode the significance of that one for her. I have a lot more ink than both of them, though.

“On the note of Hazel being a writer, I find that writers are more often than not my ideal readers. They’re a fantastic audience to write for because they appreciate language. It gave me an opportunity to explore all the different words I wanted to use and really unearth my voice.

“The rest is pure invention. Her family dynamics are entirely different. I have sisters but not one like Elle, and I have a great relationship with my mom. But for the character in this book, it made sense to isolate her in as many ways as possible because when we’re isolated, we might feel compelled to act out of character or cling to the first person who gives us the time of day. Or night, in Hazel’s case. I never dropped things off the side of a bridge or chased down a drug dealer. And I like to think that she is more awkward than me, but…I guess I can’t really be the judge of that.

“It’s kind of frightening cracking your skull open and letting people take a peek inside—but I think there’s something to be said about literature that’s rooted in raw honesty. This juxtaposition of real feelings in a fictional world with fictional characters. There’s truth to fiction, and that’s why I love Nikolai Kole’s catchphrase, ‘Everybody lies,’ which, by the way, I borrowed from my husband.

“I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention my husband. My writing process is this: It always starts with a character for me. I think of a character and their nuances, what makes them tick, who else is in their world, and I start creating a situation wherein they have to act—the plot. Once I have a loose idea of who these people are, I create a murder board. It’s a giant whiteboard on the wall of my writing room. I go to Google to get character references—some are actors, others are random images I find online—and that helps shape the character a great deal. I discover so much when I shop for reference photos: maybe someone has a devious expression, someone else is smoking a cigarette, etc. Then I put them all up on my board and write about how they interact with one another. Each character gets an overview and four bullet points: Uniquities, Vices, What do they want most, and What are they afraid of.

“In all of this, from helping me with my murder boards to being my first reader, to answering all of my morbid questions, and simply inviting me into his world, my husband has been an invaluable asset. And the fact that I can just poke my head out of my office and ask about how he might approach a particular crime scene, what he would say in an interview, etc., is something I’m sure a lot of crime fiction writers wish they had. Plus, he is brutally honest, so he will tell me if something isn’t working, or if I need to make the whole thing more ‘salacious,’ as he puts it.”

Also brutally honest, as it turned out, was the whole publishing process, at least for a while: “I tried and failed for years to land an agent. Lots of cold-querying, even pitching at conventions. That was nerve-wracking. HELLO, TRANSCRIBER was the fifth manuscript I queried. Some of the best advice I read about querying was, ‘Don’t stop until you reach 100 rejections.’

“When I discovered my agent, Sharon Pelletier, I felt this instant connection. She is a former Barnes & Noble bookseller like myself, is pro-Oxford comma, and her bio succinctly stated she isn’t into hard-drinking, hard-boiled detectives. I was sold. So I queried her, but I didn’t get my hopes up, of course. I knew that more likely than not, I would get a polite rejection. But I was wrong. I was walking to work one day when I read her email: she loved my 25 sample pages and could I send her the full manuscript. I did, again, not getting my hopes up, and the following Monday, she emailed again to ask if she could give me a call.

“It’s interesting how quickly the tables turn after you get that first phone call. I think it’s like dating. When you’re single, no one wants to date you. But once you’re matched, suddenly everyone wants to date you. I was having a tough time deciding between Sharon and one other agent who was tremendously interested in the manuscript. We’d had three phone calls, and as she was ending the third one, she said, ‘Oh, by the way, you’ll have to change the title. It’s totally wrong for this genre.’ I’m pretty open-minded when it comes to making changes, but the title was something I really loved. So I emailed Sharon and asked if she thought I should change the title. She gave me this great explanation as to why she loved it, and here we are.

“I worked with Sharon for months to whip HELLO, TRANSCRIBER into shape. She’s not only one hell of an agent, she’s one hell of an editor, too. While she loved the voice, there were some plot elements that weren’t working, and we ironed them out together.

“While on submission, the manuscript was being well-received but ultimately getting rejected. I paid attention to the common feedback—too literary, not enough suspense. There was one editor in particular, Leslie Gelbman from St. Martin’s Press, who provided really thoughtful feedback and what she would like to see if I decided to revise and resubmit. I remember I was going on a work trip to Ohio for several days. So while I was in the airport, on the plane, or in my hotel room at 4 a.m., I overhauled my manuscript. When I returned, we resubmitted, and she came back with a two-book deal. There were other editors who were interested at that point, but…Leslie believed in me first, and she was ready to do a deal that day. I think that speaks volumes—someone believing in you when no one else does.”

After reading HELLO, TRANSCRIBER, everyone will be a believer in Hannah Morrissey. She’s already finished the second book, Widowmaker, an “unofficial” sequel.

I say “unofficial” because, while it takes place in the same world, it features different main characters. (You’ll recognize a supporting character, though!) This one is third-person POV, toggling between two protagonists: Morgan, a photographer, and Hudson, a detective. Their worlds collide when a classic car is extracted from Lake Michigan with a body found inside, and Morgan will have to navigate the dark recesses of her memory to help solve the mystery.

“I have plans to continue exploring Black Harbor—I’ve got my murder board up for Book 3 and an outline complete—so we’ll see what happens!”

*****

Neil Nyren retired at the end of 2017 as the executive VP, associate publisher, and editor in chief of G. P. Putnam’s Sons. He is the winner of the 2017 Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Among his authors of crime and suspense were Clive Cussler, Ken Follett, C. J. Box, John Sandford, Robert Crais, Jack Higgins, W. E. B. Griffin, Frederick Forsyth, Randy Wayne White, Alex Berenson, Ace Atkins, and Carol O’Connell. He also worked with such writers as Tom Clancy, Patricia Cornwell, Daniel Silva, Martha Grimes, Ed McBain, Carl Hiaasen, and Jonathan Kellerman.

He is currently writing a monthly publishing column for the MWA newsletter The Third Degree, as well as a regular ITW-sponsored series on debut thriller authors for BookTrib.com, and is an editor at large for CrimeReads.

This column originally ran on Booktrib, where writers and readers meet.

- The Big Thrill Recommends: ORIGIN STORY by A.M. Adair - November 21, 2024

- Deadly Revenge by Patricia Bradley - November 21, 2024

- Unforgotten by Shelley Shepard Gray - November 21, 2024