Up Close: Karen Odden

As the Thames Ebbs and Flows, So Does the Trust in Scotland Yard

By K.L. Romo

By K.L. Romo

Author Karen Odden once again brings Victorian England to vivid life in her new thriller, DOWN A DARK RIVER: An Inspector Corravan Mystery.

Inspector Michael Corravan is trying to prove that Scotland Yard is an effective and necessary institution. After the recent trial and scandal involving several detectives, the public distrusts their work, and most newspaper reporters agree. But Corravan had come to the Yard to remove himself from the corrupt River Police, where he previously worked, and he’s determined to prove that the Yard is now trustworthy.

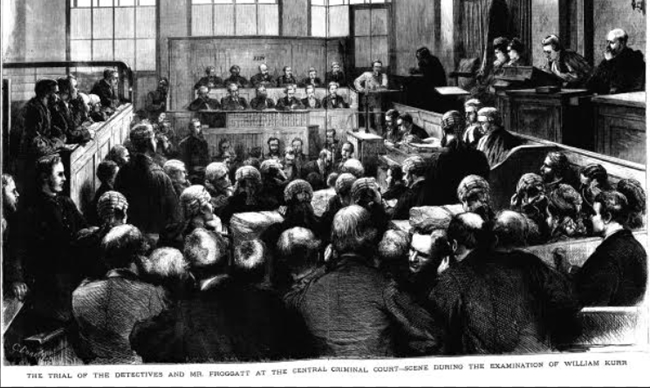

Scotland Yard appointed a new director, Howard Vincent, after the bribery scandal. Corravan resents him because he has no prior police experience, and he’s not sure how effective a man with no experience can be. Vincent assigns Corravan to investigate a dead woman floating down the Thames in a small boat—a lighter—used to transport goods. Of course, Corravan has experience working the river, but he’s none too happy to be pulled away from the missing person’s case he’s been working on for three weeks, with no results. And he knows the head of the River Police—Blair, his former boss—will resent his involvement.

The case of the missing woman almost bothers him more than the murder. Corravan’s own mother disappeared when he was 11 years old, so he knows first-hand what her family is going through. As far as he’s concerned, “A dead body is certain, and once you’ve seen it, you’ve faced the worst. But a missing person? Your imagination can take the most violent, depraved acts and multiply them endlessly until the moment she is found.”

It surprises Corravan that the dead woman appears to be upper class. How did a socialite come to be in the river district? As he and his partner, Stiles, investigate, he continues to look for the missing woman, whom he finally finds in the last place he’d expect to find the wife of a wealthy man.

As more women are attacked and found floating down the Thames in lighters, Corravan must figure out how they’re connected to stop the killer. And is the missing woman involved somehow? When he realizes he’s been looking at the clues the wrong way, the outcome is not what he expected.

Odden’s descriptions of life in London during the late 19th century make readers feel like they’re walking along the Thames in a wet foggy-morning mist. Her characters experience the prevalent misogyny, bigotry, and poor treatment of the “lower classes.”

She normally writes her Victorian thrillers with a female protagonist, but this time, her hero is male. Her details about the class system in that era in London seem all too real. Corravan is a former orphan who grew up in the rough Whitechapel area, being taken in by a friend’s mother after living on the streets. He even made his living for a time as a bare-knuckles boxer, then as a river worker.

Odden’s narrative not only gives readers a complicated mystery to solve, but explores the social issues of life in London at that time. Here, she talks with The Big Thrill about her motivation, research, and writing a social commentary.

What was the inspiration for the story in DOWN A DARK RIVER?

Often the inspiration for a book comes from a harrowing story I read or heard. It gets its claws into me, and I know I must share it in a book.

With DOWN A DARK RIVER, years ago I read an article about race and the law in the US. One vignette in the article was about a young Black woman in the South who was jaywalking across a quiet street. A white man driving too fast and under the influence of alcohol hit her. She was in the hospital for two months, but a judge awarded her only $2,000—ostensibly because she’d been jaywalking. The injustice horrified me. But even more striking was the conclusion to the story: The victim’s father threatened not the judge but the judge’s daughter—an attempt to put the judge in his own shoes, to make the judge understand what it was to almost lose his child.

A scene from the “Trial of the Detectives” in 1877 at the Old Bailey courthouse, London. In DOWN A DARK RIVER, Odden’s Inspector Corravan must not only solve crimes but also strive to reestablish the Yard’s reputation.

This was a stark reminder that revenge is not always as simple as the brief phrase “an eye-for-an-eye” suggests. Sometimes justice fails at the level of the symbol—a guilty verdict, monetary compensation, or a public apology. Revenge is sometimes an attempt to make one’s suffering material to someone else—to communicate one’s experience to someone who, out of a lack of compassion or ignorance or willfulness, is refusing to acknowledge it.

I wanted to explore revenge and empathy, but in a Victorian setting. I wanted to write about the cost of not having empathy, the limitations of “legal justice” in a flawed world, and how many of us often want to hear someone say, “I understand.”

In your previous novels, the protagonists were women who overcame the misogyny of their times. Why did you decide to create a male protagonist?

Given that the vignette (above) played itself out in the court of law, with a male judge and a male perpetrator, it steered me toward the world of the police and the courts—all staffed by men in the Victorian era. (The first Police Women Patrols weren’t until 1919 in London.)

I’d also written two novels with Scotland Yard Inspector Matthew Hallam as a secondary character. He is the brother of my protagonist Nell in A Dangerous Duet and the love interest of Annabel in A Trace of Deceit. So I knew a good deal about the Victorian police from Haia Shpayer-Mokov’s brilliant book, The Ascent of the Detective, and other sources.

The New Houses of Parliament and the Thames, by Henry Dawson (1811-1878). Inspector Corravan’s office at Scotland Yard overlooks the Thames, which he describes as both “the lifeblood of the city” and “a cesspool, a receptacle for the entire city’s detritus, complete with entrails and rotting corpses.” Most etymologists agree the word “Thames” derives from the Sanskrit “Tamasa” meaning “dark river” or “dark water,” and the word spread from India through the Celts to Britain.

What interested me is how a scandal in 1877 shredded public trust in plainclothes police and nearly shut down Scotland Yard. Four veteran Yard detectives were convicted of taking bribes from con men who stole upward of £10,000 from unsuspecting victims (about $2.2 million in today’s money). The newspaper headlines excoriated the Yard, and the public crammed the courts at the Old Bailey for over a month.

I thought about how difficult it would be for a policeman to solve crimes, to convince people to speak to him, much less trust him, in the wake of that. So I put Michael Corravan—who had to strive to survive a childhood in Whitechapel and earn money to live—in another position of striving, this time to earn the public’s trust.

Inspector Corravan is a former river worker and bare-knuckles boxer from the tough neighborhood of Whitechapel. What about the social commentary of the times is portrayed in his character?

Through Corravan’s eyes, we see both the desperate level of poverty in some sections of Victorian England and the enormous social, economic, and political changes that were happening across England in the 1870s.

In 1867, the Second Reform Act extended the vote, so at last, working men had a say in how their country was run. This Act granted the vote to all householders in the boroughs, to lodgers who paid rent of £10 a year, and to agricultural landowners and tenants with tiny amounts of land. The Act roughly doubled the electorate in England and Wales from one to two million men.

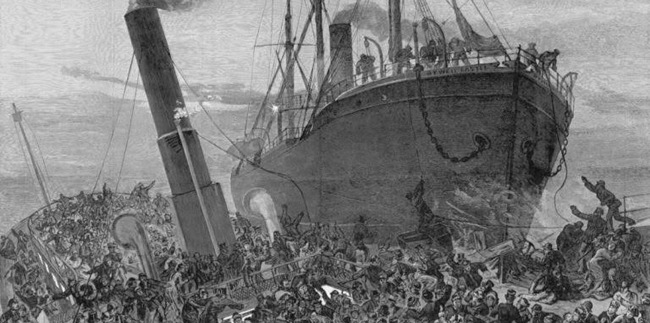

The Princess Alice disaster on the Thames, September 3, 1878. The Princess Alice, a small pleasure steamer, is on the left, breaking apart and sinking in the Thames as the passengers teeter and flail on the deck, and the Bywell Castle is the huge collier on the right. Over 600 people drowned.

In addition, with rising literacy rates and an explosion of newspapers (over 1,000 in England in 1870), people were becoming informed on all kinds of social issues, and dozens of laws were passed that altered many facets of society. For example, with the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act, a working woman could keep her wage instead of handing it over to her husband. The 1870 Education Act made it mandatory for children to be in school until age 12. There were laws that protected infants, set limits to working hours in the mills, prevented cruelty to animals… the list goes on and on.

I wanted to put Michael Corravan in this world, where everything is changing—because then he, too, would have to change.

You have a huge amount of expertise regarding Victorian England. Did this novel require additional historical research?

Yes, heaps! I knew a good deal about Scotland Yard and the police, but I had to learn about the history of the Thames River and its tides and boat traffic, bare-knuckles boxing clubs, high-end French jewelry, sleazy brothels, the gentlemen’s clubs on Pall Mall, health sanatoriums, and the River Police division at Wapping High Street.

Odden’s home office, complete with a map of 1870s London on the wall (the colored papers mark important sites in her book) and Rosy, Odden’s “faithful 17-year-old beagle-muse”

Is there a message you’d like readers to take away from the book?

I never want to write a book that sounds preachy. That said, I hope this book might cause people to reflect upon not just what it means to cause pain to another person, but also the secondary cruelty of disavowing that pain, of saying—or pretending—it doesn’t matter. I believe in the transformative power of listening and empathizing. Most of us want or need acknowledgment of our lived experience.

Can you give us a hint about your next novel?

As I was researching the history of the Thames, I came across the Princess Alice disaster in 1878, about three months after DOWN A DARK RIVER ends. The Princess Alice was one pleasure steamer in a fleet of four that traveled each day from the Tower Bridge in London out to Steerness (where the Thames meets the sea) and back, making stops at picnic areas and gardens.

On September 3, the Princess Alice was rounding Tripcock Point when a huge coal ship, the Bywell Castle, rammed her side, sending over 600 passengers into the river. Most of them drowned. Because passengers could ride on any of the four steamers, there was no manifest and no clear record of who was on the boat. This suggested all kinds of possibilities, as well as being a tragedy that presaged the Titanic disaster decades later.

The accurate history is that they found both boats to be at fault; but for my book, I wondered: What if someone had caused the accident? Could someone turn it into economic or political gain?

What advice can you give other writers?

I am often inspired by a harrowing or startling story, but once I have that, I spend months developing characters—not just my main character but my secondary characters—anyone who’s part of either the “character arc” or the “plot arc.” I write their stories from their point of view (for example, the one for Matthew, a secondary character in A Trace of Deceit, begins, “My name is Matthew and my mother left us when I was five”).

The easiest scenes to write are those in which I know the characters so well that I can put them in a room and let the action unfold before me, as if I were watching a movie. I observe how they move and what they say, and write it down.

Tell us something about yourself your fans might not already know.

To pay my way through college, I had a series of service jobs including bartending at the Rochester airport and working at steakhouses, exposing me to a wide variety of people. Then I sold books door to door. One day, I walked into a store, and the woman behind the counter shrieked: “Get the f— out of here!” Shaken, I retreated, gathered myself, and went into the next store. This shop owner said, “Sure, I’ll take a look!” And as I was leaving, she said, “Don’t go in there,” and pointed to the store I’d just left. “She’s going through a terrible divorce and just lost her lease.”

In that moment, something shifted inside my head. The woman’s nastiness had nothing to do with me. It helped me understand that everyone has their baggage that they bring to interactions, and when I’m building a character, I need to know not only characteristics but the character’s past story and circumstances to get inside her head.

- The Big Thrill Recommends: THE BOYFRIEND by Freida McFadden - October 29, 2024

- Booktrib Spotlight: Sarah Sawyer - October 29, 2024

- Booktrib Spotlight: Marie Tierney - October 29, 2024