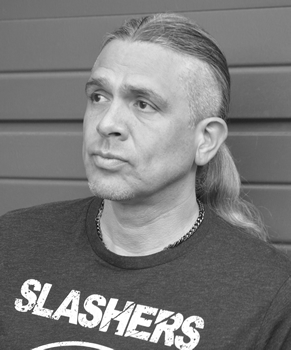

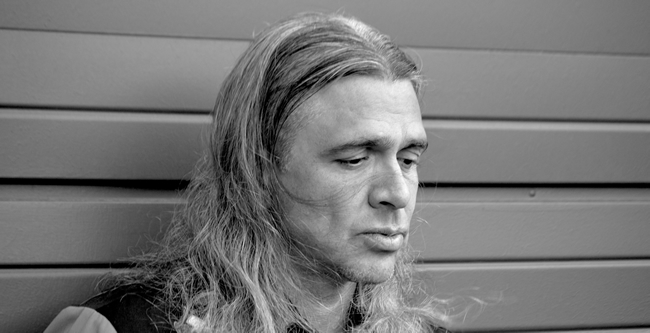

On the Cover: Stephen Graham Jones

Slasher 101

For all the lip service that’s paid to the final girl, she rarely gets her due on screen. It’s no one’s fault, really—if you’re going to squeeze a respectable body count into a 90-minute slasher movie, there’s hardly time for a deep dive into the heroine’s background and motivation (beyond a keen desire to avoid getting stabbed to death).

So the recent spate of final girl novels, from Riley Sager’s Final Girls to Grady Hendrix’s The Final Girl Support Group, isn’t just a welcome addition to the slasher canon—it’s a necessary one. Novelists such as Sager and Hendrix are exploring one of horror’s most appealing archetypes in ways filmmakers can’t.

Case in point: Stephen Graham Jones’s ferocious 28th-ish novel, MY HEART IS A CHAINSAW. Jones’s follow-up to his Shirley Jackson Award-winning breakout book The Only Good Indians (and his Shirley Jackson Award-winning novella Night of the Mannequins—Jones had a good night at this year’s virtual awards ceremony) centers on 17-year-old Jade Daniels, a half-Blackfeet girl in rural Idaho who finds solace in slasher films.

Jade has much to seek solace from: an alcoholic, abusive father; an estranged mother who barely acknowledges her existence; and few prospects of ever getting out of Proofrock, a town whose adults have failed her in every way imaginable. Jade sees her hometown through the bloody lens of the slasher films she spends every spare minute consuming, but it’s not the final girls she most identifies with; it’s the slasher, usually an outcast who visits gruesome revenge on a community that has wronged him.

Granted, it’s not hard to imagine Proofrock as a place where blood seeps out of the ground with every footfall. The town’s grim history already includes a murderous lake witch, a terrifying preacher of unknown origin and his drowned congregation, and a summer-camp massacre. So when Jade finds evidence of a pair of murders on nearby Indian Lake, she’s convinced this is the “blood sacrifice” that will kick off Proofrock’s own slasher cycle, and that it’s up to her to find and prepare the final girl who will end the slaughter. But when she sets her sights on Letha Mondragon, the impossibly perfect daughter of a media scion who’s building a home in a wealthy new development known as Terra Nova, nothing works out the way Jade needs it to.

Jade is one of the most fully realized and deeply sympathetic heroines in recent horror fiction, and Jones’s book, epic in scope and cinematic in execution, feels like the definitive final girl novel. Jones is hardly a latecomer to final girl fiction, though; his 2012 novel The Last Final Girl, about a final girl who replaces her slaughtered homecoming court with girls who have survived their own slashers, preceded the current spate of novels by five years.

In his first-ever interview with The Big Thrill, Jones talks about his spectacular new book and the enduring appeal of the last girl standing.

Where did Jade come from, and how did she take shape for you?

The first time I wrote MY HEART IS A CHAINSAW, it was called Lake Access Only, and it was narrated in the plural—we instead of I—by this young boy in an iron mask, who was kind of my version of the all-knowing narrator from Tin Drum, but using The Virgin Suicide’s method of delivery. It was a ball, but . . . the story didn’t work. So I wrote it again a couple years later, erasing the Boy in the Iron Mask, but sort of keeping him via embedding the cover of Quiet Riot’s Metal Health album at the back of the book, and also using them for the then-epigraph. So with that boy still sort of there, I was kind of free to kick around the valley, splash through the water, and see who else might be lurking around. Turned around, Jade Daniels was. It was like she’d always been there. To me, she looks a lot like the Native version of Fairuza Balk’s character from The Craft. And she’s also me. When Jade gets sent home from school for wearing T-shirts the principal won’t tolerate? That was me, every couple weeks. When she’s hoarding her slasher videotapes? I remember that. All of which, I guess, is just me not answering the question, exactly. Which is to say, I don’t exactly know where Jade comes from. I just sat on the pier and looked down into the water, and Jade was walking up from it, glaring me down, daring me to ask her what she’d been doing, and why. Instead of asking, I just followed her through draft after draft, and was careful to never step on the boot laces she was dragging, because she’d probably be wearing a Freddy glove.

I kept wanting to pull her out of the book and hug her and cook her a good meal. Were you ever tempted to write an easier path for her?

Thank you. If only the people of Proofrock had felt the same way, right? But, yes, I was tempted to shape things around her . . . better. And? I gave in to that temptation, I guess. This version that MY HEART IS A CHAINSAW now is, it’s the nice version. Before, man, the story was pure meatgrinder, just chewing through bodies and lives, until there was nobody left to even throw those buckets of chum out into Indian Lake. Paul Tremblay read one of those brutal versions, I think. We’re somehow still friends. For me, though, knowing all the other ways this novel used to end, it’s sort of like it also still ends like that, just a shade away. That make sense? Like, I see Jade, but I also see, stemming out from her like a funhouse mirror, all these other versions of Jade in all the other drafts and permutations and attempts. I’m never one to world-build before I jump into a piece, but with MY HEART IS A CHAINSAW, I did walk every last inch of Pleasant Valley over the last eight years until I know in a granular, intimate way what’s going on all over the place. Which is to say, some of us world-build by taking dead-alley after dead-alley. We delete a lot, but now that we know what’s down there in those shadows, it usually ends up exerting an influence on the stuff that remains, or it casts a shadow at least, or it just makes things feel more real, finally. To me, Proofrock and Terra Nova and Camp Blood, they’re as real as anything. For me to believe in them enough to write about them, and among them, and from Cabin 5, say . . . they have to be real, they can’t just be story-things, they can’t just be made up.

It’s notable that Jade’s heritage is, to borrow your words, incidental to the story rather than instrumental. In the acknowledgements, you mention how relieved you were that your editor didn’t ask you to change that. Why was that important to you?

Way back in grad school—I think I run through this in “Being Indian Is Not a Superpower” on Electric Lit?—I turned a story in to workshop and, for the first time, I guess, one character was Native. And it was weird, the response that story got. People looked at me with different eyes, with, I don’t know, stupid “sympathy” in their hearts, all that ridiculousness. Like, their eyes got all tragic. Maybe a hawk screeched, even. But? I mean, all of my characters had always been Indian. Just, the stories weren’t about them being Indian, they were about the neighbor in the trailer park being annoying, they were about why this truck wouldn’t run . . . they were about story stuff, not identity stuff, not cultural stuff. And then when I started publishing books and doing events, so many of the questions I got, I could tell these people were using my book as a lens on to . . . “history,” the Indian Experience, all that. And I’d much rather be read as art, as a story, than be used like that. And I’ve also had the weird experience of giving someone a story to critique, and one of the notes they get back to me with was, “Hey, so this character is Indian, but—like, isn’t that supposed to matter at some point?” Which is to say, Why make this character Native if you’re not going to use that. To me, that reveals that the default setting for characters must be white. Yes? Any deviation from that has to serve a purpose. So at some point near the end, that character needs to activate his or her or their Indianness as a superpower and save the day. Thanks, but no, I don’t think so. My default setting is “Native,” is “Indian.” So with MY HEART IS A CHAINSAW, it was and is so liberating—and it’s idiotic that the world is such that it has to feel like that—that Jade could just be Indian.

Please tell me a little about your personal connection to the central elements of MY HEART IS A CHAINSAW: final girls and slasher movies.

How much time we got? I mean, slashers . . . you know, I probably fell in love with them watching Scooby-Doo on Saturday mornings, growing up. There was always a menacing monster, a crew, and then a big reveal at the end, after which Wes Craven pans up over the house, to dawn breaking over Woodsboro. And, that crew? Fred, Daphne, Velma, Shaggy, and Scooby, I wonder if they’re not the component parts of the final girl? I bet we could make that argument pretty well. Velma hits the books, Fred always wants to do what’s right, Daphne’s kind of the popular-girl cheerleader, Shaggy’s the fraidy cat, always just wanting to beat feet away from the bad scene—it serves Laurie Strode well, yes?—and Scoob’s got some serious toughness. He always gets bonked on the head or slammed behind a door or something, which knocks him silly for a bit, but then he collects, regroups, and is ready for round two. Just like Sidney Prescott. But the final girl, yeah, I think they’re one of the better character types to stand up from the gore of box-office speculation. Final girls model for us how to stand up to bullies. They show us that, at some point, you turn around and fight. Not only that, you win. But over the course of so many tellings, the figure of the final girl has kind of become an unattainable ideal, yes? She’s so perfect that she’s no longer a model, she’s just one more thing it’s impossible to ever actually be. So, with MY HEART IS A CHAINSAW, it was very important for me to interrogate that, to undermine that conception of the final girl. What I want, what I hope, what I’ve got my fingers crossed for, is that some ten- or twelve-year-old girl out there will get hold of MY HEART IS A CHAINSAW, and understand that being a final girl isn’t about how the world sees you. It’s about what you’ve got inside you. It’s about your heart, and whether you can rev it up, tear through the world.

When you were writing this book, did you feel like you were writing for the slasher faithful, or that you were reaching out to new converts?

It was a tricky balancing act because of course it’s for both the die-hard slasher crowd, all of whom probably worked in some version of the video rental store and have seen everything twice, and the crowd who might say that anything with a killer . . . that’s a slasher, isn’t it? So I had to both walk one group along with baby steps while not talking down to the other, and all the while, of course, be saying real and true and hopefully insightful or at least incisive things about how and why the slasher works.

Jones plays Werewolf: The Apocalypse with George R. R. Martin and Maria Alexander at Bram Stoker Festival 2017 in Ireland. Photo courtesy of the author

But I guess it was most important for me not to come off in any way superior just because I know this or that trivia, or because I’ve seen all these movies. You see that happen with a lot of fanbases, and it’s ugly and so unhelpful, isn’t it? Like someone can see a Wonder Woman comic with a cover that entices them to slap this book down by the register . . . at which point all the lifelong comic book readers lurking around this comic book store sneer, crowd around, say this isn’t where you start with Wonder Woman, you can’t possibly read this unless you know this whole other universe of stuff. At which point this potential reader hears the beep of a dump truck backing up to bury them in issues, and it’s suddenly not worth it, just reading this one random book for fun. I hope to never do that with a potential slasher fan. So I guess, if pressed, I’ll say that protecting those people new to the slasher was, finally, more important than not saying something the die-hards already know.

It’s not easy, stepping into a strange place. I’ll hold your hand if you want and walk you around until you’re comfortable. But be aware, when you’re on your own, you might look down to the laundry line from your bedroom window and see a menacing figure in a white mask, and things will never be the same after that.

What’s behind the spate of high-profile final girl novels we’ve been seeing lately? Do you think these books are crossing over to an audience that isn’t necessarily part of horror-movie fandom?

Yeah, MY HEART IS A CHAINSAW is following right on the heels of Grady Hendrix’s The Final Girl Support Group. And Laurie Strode’s back in a new Halloween trilogy. And there’s a lot more slasher stuff happening on the bookshelves and at the box office and the small screen. It’s so, so cool to see, and maybe be a part of. Those of us who were kind of still kids for the Golden Age, from 1978 until, say, 1986-ish, we all kind of suffer from that Born Too Late Syndrome, where we feel like the class that graduated before us actually had all the fun. I mean, yeah, the neo-slasher thing Scream kicked off in 1996 was so amazing, but it only lasted about five years. And a lot of people said that was it, there was no more fuel left in the slasher tank. But? Trick is, the slasher runs on blood and heart, right? And that, we’ve most definitely got. No, the slasher isn’t like it was in 1980. But nostalgic as we might want to wax, maybe that’s good, yes? A lot of that old stuff’s so exploitational. The Golden Age was groundbreaking and iconic and never to be repeated, but I really like where we are now, too. Grady’s interrogating what happens after the slasher cycle. So are these new Halloweens. And slashers are finding new forms—Happy Death Day, The Final Girls, Freaky, Tucker and Dale, The Cabin in the Woods, Tragedy Girls. The biggest game-changer of them all might be It Follows, even. It seems to have evolved less from Jason and Michael and Freddy than Final Destination.

But as for why this current kind of frenzy of slashers, why the market’s supporting them again . . . for my money, it’s got something to do with the last four or five years, where we’ve seen people in the news doing and saying pretty vile stuff, and then just shrugging and walking away, because they can’t be touched. Seeing this happen again and again, we eventually feel that the cycle of justice has been ruptured, and we fantasize about an avenger rising to balance the scales. Enter the slasher to feed that impulse, to allow us to believe, for two hours, for three hundred pages, for a season, that it is possible for a world to be fair. Brutal and hard to survive, to be sure. But violently fair.

Some of the best slasher stories, yours included, treat the material as modern mythmaking at its most visceral and immediate. What do final girls have to teach us about living through whatever this is that we’re living through right now?

Final girls teach us that, if we fight hard enough, we’ll make it to that point of light way down at the end of this dark, dark tunnel. We need stories of heroism, of overcoming, of survival. They make our hearts three sizes bigger.

What did you enjoy most about writing the book, and what gave you the biggest headache?

I guess what hurt the most was when my agent, BJ Robbins, and my editor, Joe Monti, both told me that the Slasher 101 pieces needed to not be six or ten pages, as they all were, but, at the maximum, two pages. They were right, of course—I was using them as a personal soapbox instead of as a character-revealing tool—but still, man, did it hurt. Seems the best revisions always do. What also gave me a headache was keeping place and geography and just basic logistics and timelines straight. None of that is my strong suit, even remotely. But to make this place a lived-in space, I had to figure out where everything was in relation to everything else, and how long it took to get from here to there. That is, by far, my least favorite part of writing. Leave the map drawing to the fantasy writers. The endpapers of their books look great with those maps, and I’m always jealous. Horror writers, though, we’re—okay, at least me—used to working in the darkness, just feeling our way through with outstretched fingers.

Can you say anything at all about what you’re working on now?

Can’t say as much as I want to, of course, but for the novel I’m in notes on . . . it’s another slasher, of course. And I’m also doing some television work and some comic book stuff, some of which hopefully announces soon enough that my head doesn’t explode from not being able to say it. Insert Scanners gif here, yes. But give that dude some longer hair, maybe. Or, no—we can use that head-explosion from Maniac, yes? That’s Sir Tom Savini, even. And, now that I think about it, just leave their hair as-is. I don’t think I want to see some version of my own head explode. I’m way too spooky for that. It’s kind of why I’m a horror writer, even.

- Between the Lines: Rita Mae Brown - March 31, 2023

- Between the Lines: Stephen Graham Jones - January 31, 2023

- Between the Lines: Grady Hendrix - December 30, 2022