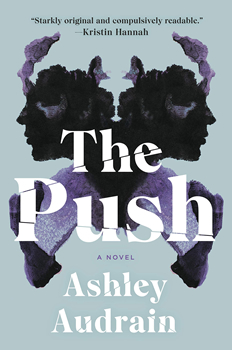

BookTrib Spotlight: Ashley Audrain

A New Mother Discovers the Experience Is Not What She Hoped For

—and Everything She Feared

“One day you’ll understand, Blythe. The women in this family…we’re different.”

The woman talking in Ashley Audrain’s scorching novel THE PUSH is Blythe Connor’s mother, Cecilia. Cecilia’s mother, Etta, hung herself at the age of 32. Cecilia herself left the family when Blythe was only 11. “I don’t want you learning to be like me,” she told Blythe.

And now Blythe has her own daughter, Violet, a child about whom she has “thoughts most mothers don’t have.” She’s convinced there is something wrong with the girl, the way Violet looks at her, the casual cruelty with which she treats her classmates in preschool, the way she stares in the night at Blythe’s new baby, Sam, the child with whom Blythe instantly felt the connection she never had with Violet.

Her husband dismisses her fears. Others say she’s just tired—hang in there, it’ll get better. And maybe they’re right. But Blythe knows who she came from, what she herself has become, what she thinks she’s seeing now.

And she knows what she thinks she saw happen when the little boy at the playground died. She will not let that happen to Sam.

With that, Audrain ramps the novel up to an entirely new level. It becomes an extraordinary psychological thriller, a tour de force of suspense and dread as Blythe looks at everything through new eyes, even as we ourselves begin to wonder how much is real, how much is not, and are yet unable to shake the gnawing doubt: What would you do if the unthinkable happened, and you were the only one who saw it? Would anyone believe you? Would you believe yourself?

And just as horrifying: Could it happen again?

“We’re all entitled to have certain expectations of each other and ourselves,” Blythe tells the reader. “Motherhood is no different. We all expect to have, and to marry, and to be, good mothers.”

“We’re all entitled to have certain expectations of each other and ourselves,” Blythe tells the reader. “Motherhood is no different. We all expect to have, and to marry, and to be, good mothers.”

But what if everything you thought you knew about motherhood—everything society has always told you—is wrong?

This is a raw, immediate, propulsive, thought-provoking book, with an ending that hits like a sledgehammer. You’ll be talking about it for a long time.

“I started writing the novel,” Audrain says, “when my son, who had some health challenges, was six months old. While I was already very interested in motherhood as a topic, this experience made me think a lot about the expectations of motherhood that society puts on us, and that we put on ourselves: how it will be, how we are meant to feel and cope, what we think our lives as mothers will look like.

“Becoming a mother myself gave me a different understanding of these themes from the inside, which compelled me even more to write about it. That said, the novel evolved over about three years, and ended up in quite a different place than where it started. The more I revised over time (and there was a lot of revising!), the sharper the novel focused on the inner conflict of Blythe and the questions at the heart of the story. Thankfully, my own experience was nothing like that of my main character!

“I find a lot of satisfaction in exploring our common fears, perhaps as a way of understanding them better in myself. I think a lot of us have flashes of nightmarish thoughts cross our mind as we’re expecting children or raising children, and I found it fascinating to let my mind wander further down that path to consider the ‘what if’ scenarios in the lives of these characters.

“The degree to which both nature and nurture shape a person is also something that fascinates me. What makes a person with a loving, positive upbringing behave unconscionably? How does a person with a particularly traumatic childhood completely break the cycle of certain behaviors with their own families? When I hear or read about a person who has committed a serious crime, I always think about their parents. I think the evolving science of inherited trauma is particularly interesting, the way a severe emotional experience can physically alter the cells and behavior of that person’s own children. And of course, raising children now with my partner, the idea of nature and nurture is often on my mind as we see who they’re becoming and how they behave. It’s incredibly interesting to observe.”

Audrain’s book is full of sharp observations, vivid phrasing, paragraphs that cut like a knife. Where did that style come from, and, once she got deep into the science, did she have to do much research?

“I think the pace and intensity of the novel is likely influenced by the way in which I wrote and revised: in short blocks of time, often racing against the clock for when I had to get back to my kids. Also, I was usually writing from a place of being very tired, not unlike my main character!

“As for the research, I didn’t do a lot before or while I was writing, but I did when I was in the later revision stages, when I was more conscious of ensuring certain things made sense from a psychological perspective, and at one point I asked a psychologist to read the novel through a lens of mental health sensitivity. I came across some really interesting papers, in particular one from 1975 in The American Academy of Child Psychiatry titled “Ghosts in the Nursery”—I think that’s such a compelling metaphor for the relationship between a parent’s own early childhood experience and the treatment of their children. And I found a wonderful quote that became the epigraph in the novel while I was researching theories on matrilineal relationships. It’s from a book called When the Drummers Were Women: A Spiritual History of Rhythm, by Layne Redmond.”

Here it is: “It is often said that the first sound we hear in the womb is our mother’s heartbeat. Actually, the first sound to vibrate our newly developed hearing apparatus is the pulse of our mother’s blood through her veins and arteries. We vibrate to that primordial rhythm even before we have ears to hear. Before we were conceived, we existed in part as an egg in our mother’s ovary. All the eggs a woman will ever carry form in her ovaries while she is a four-month-old fetus in the womb of her mother. This means our cellular life as an egg begins in the womb of our grandmother. Each of us spent five months in our grandmother’s womb, and she in turn formed within the womb of her grandmother. We vibrate to the rhythms of our mother’s blood before she herself is born….”

A lot of other books have influenced Audrain. For instance, THE PUSH has won notable comparison to Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk about Kevin. “That this novel is being used in the same sentence as We Need to Talk about Kevin is a generous compliment,” she says. “In terms of influences, I’ve always gravitated toward darker, more psychological stories that explore the contemporary lives of women (which won’t be a surprise!). I was completely rapt as a teenager by then-popular books like White Oleander by Janet Fitch, She’s Come Undone by Wally Lamb, and The Deep End of the Ocean by Jacquelyn Mitchard. I also remember devouring a set of anthologies called Dropped Threads: What We Weren’t Told, edited by Carol Shields and Marjorie Anderson—I was fascinated by the way women wrote so candidly about their personal lives. Those kinds of books have always been my leaning and have influenced what I want to write about. My reading expanded much wider once I worked in publishing and had exposure to so many more authors than I’d normally pick up (which was an invaluable education as a writer), but I still always gravitate back to books that dig deep into the female experience, whether it’s thrilling psychological suspense, literary fiction, or memoir. I love a book that I can’t put down because I want to uncover the ‘why’ of what’s happened, but I also want the writing to be so compelling that I can savor its sentences at the same time.”

Her mention of publishing refers to the fact that she was the publicity director of Penguin Canada for two years. How did being on the inside help (or not!) as she wrote and sent out her book, and how did it influence her expectations and understanding of the publishing process?

“I am incredibly fortunate that mine was a relatively smooth process from start to finish. I was privileged to be able to work on this novel for over three years while I had my two children (I have a very supportive partner, and we had help with childcare). This included a really positive experience with a former book editor who did a manuscript evaluation that I learned a lot from. I also had several trusted, honest, and encouraging readers along the way. Shortly after having my second child, I rewrote about three-quarters of the novel—which was a painful decision, but I knew the changes were working to make it a better story. At the point when I felt the novel was as good as I could make it, I began querying agents, and thankfully heard back pretty quickly. I felt an instant connection with one of those agents, Madeleine Milburn, and from there it was a dreamlike whirlwind. We had the first book deals within about a week, and it all took off from there. Madeleine is a wonderful champion and a true life-changer. I still look back on that period of time in complete disbelief that it all happened the way it did, and I’m grateful for it every day.

“As for the publishing process, being in the business has given me such valuable insight. I know from being on the other side that it’s a mix of art and science that makes a book work in the market. There’s often huge unpredictability in the publishing industry, which is part of what makes it so exciting. My experience has also given me insight into just how many people it takes to get a novel into the hands of readers—it’s incredible how many efforts have to come together, from the copyeditors to the book designers to the marketing assistants to the sales reps in the field…not to mention the editor you work with so closely to shape the book into the best thing it can be. There is so much passion behind the scenes in publishing, and I can really feel that now on the receiving end as an author. Publicists have a particularly exciting role in the process, and it’s hugely satisfying when a well-crafted plan works…but it’s also a tough job as the media landscape changes, and the expectations of everyone involved can be very hard to manage. Especially now. I am grateful for every little bit of publicity for THE PUSH and know there’s a tireless effort on the other end.”

That effort has spurred worldwide interest in her novel, and little wonder. On the first page of the advance galley of THE PUSH, the book’s editor and publisher, Pamela Dorman, discusses why: “The early responses I’ve gotten from readers have been astonishing. Every reader wrote me nearly the moment he or she finished and said, ‘We need to talk about THE PUSH …’ I believe everyone who reads it will want to talk about it right away….It is the kind of book that will be a touchstone for women readers, in particular, for years to come.”

She’s right.

*****

Neil Nyren retired at the end of 2017 as the executive VP, associate publisher and editor in chief of G. P. Putnam’s Sons. He is the winner of the 2017 Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Among his authors of crime and suspense were Clive Cussler, Ken Follett, C. J. Box, John Sandford, Robert Crais, Jack Higgins, W. E. B. Griffin, Frederick Forsyth, Randy Wayne White, Alex Berenson, Ace Atkins, and Carol O’Connell. He also worked with such writers as Tom Clancy, Patricia Cornwell, Daniel Silva, Martha Grimes, Ed McBain, Carl Hiaasen, and Jonathan Kellerman.

He is currently writing a monthly publishing column for the MWA newsletter The Third Degree, as well as a regular ITW-sponsored series on debut thriller authors for BookTrib.com, and is an editor at large for CrimeReads.

This column originally ran on Booktrib, where writers and readers meet:

- The Big Thrill Recommends: ORIGIN STORY by A.M. Adair - November 21, 2024

- Deadly Revenge by Patricia Bradley - November 21, 2024

- Unforgotten by Shelley Shepard Gray - November 21, 2024