Between the Lines: John Douglas

Revisiting the Long and Dark Shadow of a Killer

By Dawn Ius

By Dawn Ius

The name John Douglas is familiar to anyone involved in forensic science—and to be fair, true crime junkies across the globe, and to most viewers of the hit Netflix show Mindhunter. The renowned profiler, now retired from the FBI, has spent the last 40 years interviewing and studying some of North America’s most notorious serial killers. Think Edmund Kemper, Charles Manson, Richard Speck.

His outstanding body of forensic work is featured in numerous books—many of which were written in conjunction with Mark Olshaker—including 1995’s bestselling Mindhunter. With THE KILLER’S SHADOW, the first book in a new series featuring profiles on individual criminals, Douglas and Olshaker take us back to 1977 and the FBI’s pursuit and eventual capture of White supremacist serial killer Joseph Paul Franklin.

This was Douglas’s first gig with the FBI—a make-it-or-break-it case—and as he shares in this interview with The Big Thrill, one that had a profound effect on him personally and professionally.

Unfortunately, THE KILLER’S SHADOW is both a timely and relevant book—is that one of the factors that helped you decide to write his story at this time?

That was certainly one of the factors. Our editor, Matt Harper, wanted us to begin a new series in which we’d focus on an individual crime or criminal rather than a broad spectrum as we had in all of our previous books. Matt suggested that in addition to a compelling story, we choose our subjects based on which crimes and criminals had affected me most on a personal level and/or contributed to our understanding of criminal behavior. Joseph Paul Franklin was therefore a natural one to start with. It was early in the development of the FBI’s profiling program and the directive for me to get involved came from the Civil Rights Division at headquarters, so it was really a make-or-break case for our entire program. Franklin had killed at least 22 individuals and seriously wounded others, he was highly mobile, he killed in a variety of different methods, and he was the first serial killer I had faced who was motivated by racism, anti-Semitism, and White supremacy, so his mind worked in a far different way than most of the serial predators I had studied. And, as you suggest, his story is timely and relevant today, which was one of our prime motivations. Dylann Roof, who committed such heinous violence at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina in June 2015 was certainly among Franklin’s spiritual children and acted with the same intent: to foment a race war in the United States. We also wanted to show that words really do matter, whether they’re the blatant screed of an out-and-out hater or the dog whistle of a political leader only too happy to sow anger and divisiveness for personal advantage.

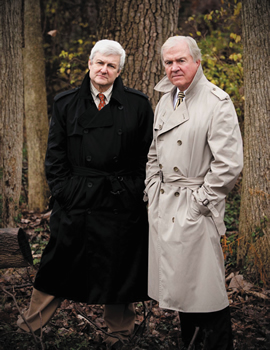

Douglas Olshaker: Douglas (right) with his frequent cowriter, Mark Olshaker. Photo credit: Philip Bermingham.

You’ve interviewed and seen a lot over the years—where does Joseph Paul Franklin sit in terms of the most chilling serial killers you’ve come across?

There are many ways a serial killer can be chilling. There are the ones like Lawrence Bittaker and Roy Norris, and Leonard Lake and Charles Ng, who got their pleasure in life out of sexually assaulting, torturing, and murdering young women and recording their crimes so they could relive them later; Dennis Rader, the self-proclaimed “BTK Strangler” in Wichita, Kansas, whose satisfaction came from watching his victims slowly die; and Richard Trenton Chase, who believed he had to drink the blood of his victims to stay alive.

Joseph Paul Franklin was chilling in an entirely different sense. He had little to no personal interest in most of his victims; he didn’t even know their names. They were completely depersonalized to him. He killed them merely because they were African American, interracial couples, or Jewish. And what was personally so scary and upsetting to me was that unlike other serial killers, who generally don’t really “inspire” others to follow in their footsteps, Franklin became an example and a hero to many haters and White supremacists. In other words, his influence went far beyond his own actions, which is why this killer’s shadow is still so long and dark.

Why was his case so hard to crack for investigators?

As I mentioned earlier, he was highly mobile, and he had virtually no direct contact with his victims, so there was little forensic or behavioral evidence to go on. And since he had several different means of killing—long-distance sniper rifle, up close with a handgun, and bombing—it was difficult for a long time to link the cases to a single individual. Also, he was highly disciplined in certain aspects of his life, making no friends and being meticulous about false identities, and changing weapons and vehicles after every crime. He was also a detailed planner. So for a relatively long time, there was very little for investigators to go on. For that and other reasons, we hope his story, my part in his capture and interrogation, and my eventual interview and confrontation with him at the Marion Federal Penitentiary in Illinois will be the kind of “what happens next?” thriller and insight into the criminal mind that will interest readers.

In 2018, Douglas helped investigators search a piece of property in Spartanburg County, South Carolina, where serial killer Todd Kohlhepp claimed to have buried two bodies.

It’s evident that this case had a profound impact on you, beyond it being your first for the FBI—how difficult was it for you to revisit this case?

It’s always difficult to revisit the emotional aspects of any case in which victims suffered so terribly. But that is what we do. To learn from any case and be able to apply it to the discipline of profiling and behavioral science, you have to be willing to revisit it. In our books, we try very hard to personalize the victims, their survivors, and the investigators—they are the real heroes—and never glorify the criminals. I have taught so many cases to new agents and police fellows at the FBI Academy and around the United States and the world that I am used to revisiting even the most heinous cases. I’m afraid it goes with the territory.

Franklin said in one of the interviews that he was influenced by reading books such as Mein Kampf. In today’s society, social media allows people to access similar messaging—faster. What parallels are you seeing—and what do you think we should learn from cases like Franklin’s?

Franklin, like so many other serial offenders, grew up in a dysfunctional, poverty-stricken environment in which he was terribly abused by both of his parents. That environment was also highly racist, since he was born in Alabama in 1950. The combination of nature and nurture that we write about in just about all of our books produced someone in whose psyche two warring elements played out: a deep-seated sense of inadequacy, in conflict with an equally powerful feeling of grandiosity and entitlement. This ongoing conflict was triangulated by a lack of empathy for other human beings and resentment against society in general for his lack of personal success and privilege. Because of his anger and inherent racism, reading Mein Kampf as a teenager was really an epiphany for him, “explaining” that what he was feeling and experiencing was not his fault, that there were specific others to blame, and that there were groups he could look down on as inferior. This ultimately evolved into the sense of mission that propelled him on his murderous spree. It was what gave his life meaning.

Today, it is much easier to be influenced by the Internet and attract “lone wolves” like Franklin than it was in his time. This is one of the reasons the White supremacists and right-wing extremist movements are so worrisome today. The challenging and scary part for those of us in law enforcement is that it is extremely difficult to determine who of the presenters and haters will be content to be like the marchers down the streets of Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, chanting “Jews will not replace us!” and “Blood and soil!” (a slogan central to Nazi Germany) and who will go on to become like Dylann Roof, fulfilling themselves and their resentment and hatred through murderous violence.

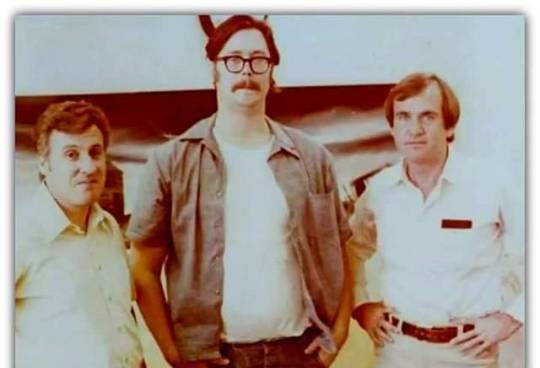

Douglas (right) and Robert Ressler (left) interview serial killer Edmund Kemper at the California State Medical Facility at Vacaville. Photo credit: Courtesy of the FBI.

Are you ever surprised with what you find out about serial killers?

I have studied serial killers and repeat predators for more than 40 years now, and there are many similarities among them. But each one I study reveals something new.

THE KILLER’S SHADOW—and other previous books—are co-written with Mark Olshaker. What do each of you bring to the process, and what does that collaboration process look like?

Mark and I have been working together longer than I did with any of my FBI colleagues, so we tend to think alike at this point. We used to joke about him being a writer pretending to be a detective and me being a detective pretending to be a writer. But it is really more like a real-life version of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. Mark says that he has had two decades of being personally tutored by me in behavioral science and investigative techniques, and I have learned much better how to express myself and tell a story from him. Since I retired from the Bureau, we have even investigated and analyzed cases together, such as the murder of Meredith Kercher in Perugia, Italy, in 2007, for which her American student housemate Amanda Knox and her new Italian boyfriend Raffaele Sollecito were accused, tried, and convicted. After carefully investigating and analyzing the case, Mark and I realized the police and prosecution’s theory was impossible, and became strong advocates for their exoneration. So that’s a long way of saying that Mark and I are true collaborators, and we go over every aspect of the research and writing process together.

Are there any cases you have not yet covered in book form that you would absolutely not want to revisit?

There are some that would be emotionally painful to revisit, but every time I think of a victim and what she or he went through at the hands of a monster, I know that my own discomfort is small compared to theirs, and if there is something important, informative, or inspiring in their story, we owe it to them to have it told.

I was so sad to see that Netflix wasn’t renewing Mindhunter. How did you feel about the show’s interpretation of your book?

We were very pleased by the interpretation. Although they took some liberties with the characters representing me and my then-partner Bob Ressler, the spirit and what the characters did and discovered was very true to the book and the process through which our form of behavioral profiling and criminal investigative analysis were developed. Director David Fincher made what we think was a wise decision to somewhat fictionalize our characters for the sake of drama, but to portray the criminals with their real names, looks, personalities, and histories. Having interviewed and confronted such serial killers and predators as Edmund Kemper, Charles Manson, Richard Speck, and Jerome Brudos, for example, I was stunned by how good and accurate the portrayals were. My wife teased me about the sex in the first season, but I fully understand that the characters have to be more “interesting” than us. Mark and I became close friends with the two lead actors, Jonathan Groff and Holt McCallany, and we all hold out hope that the series might be resumed at some point. In the meantime, we are exploring other possibilities.

How do you feel about the vast number of “amateur” sleuths that have emerged over the years? And why do you think we, as a society, are fascinated with true crime, particularly when it comes to serial killers?

We certainly respect the effort and dedication of people who commit themselves to studying and going deep with an individual case, trying to solve it. In several notable cases, such as the Golden State Killer, the results have been truly impressive. On the other hand, we don’t have much respect for the so-called profilers who ply their trade on television. They are almost always superficial and sometimes, when an UNSUB is following the coverage of his own crimes in the media, the results can be truly harmful, as was the case with the DC Sniper series in 2002. During that reign of terror, I was asked repeatedly by the media to comment, but I refused since I had not been part of the investigation and would therefore just be speculating. That’s not how profiling and proactive investigative strategy should work.

As to why we are so fascinated by crime and serial killers, we think it is because it is the basic stuff of the human condition, writ large and at the extremes. Of course, there is the vicarious thrill of something scary, like a roller coaster or a haunted house that we know will not actually hurt us personally just by reading about it or watching it in the media. But on a deeper and more profound level, I think we are all interested and intrigued by why people do the things they do, especially things that—thankfully—seem so foreign to our actual experience. Then, we all like a good story, and crime often provides us with very intriguing stories, complete with a built-in moral. When you stop to think about it, we as investigators have to take the evidence—be it physical, forensic, or behavioral—and analyze and interpret it to the point in which we can make it into a coherent story of what happened. That is what investigation and criminal justice is all about.

Can you share anything about what you are working on next?

With our long-time researcher Ann Hennigan, we are working on the second book in this new series, about the murder and hunt for the kidnapper and killer of high school senior Shari Faye Smith and nine-year-old Debra May Helmick in Columbia, South Carolina, in 1985. For reasons that will be revealed in the narrative, this was one of the most emotionally fraught cases of my entire career, in which I very reluctantly decided to use Shari Faye’s sister as “bait” to lure the unknown killer. The case is also important because it is one of the most successful collaborations of traditional police work and investigation, behavioral profiling and proactive strategy, and cutting-edge forensic science. So we think it will be fascinating to readers, as well as reveal one of the most moving, inspiring, and heroic victims I have ever encountered.

- AudioFile Spotlight: March Mystery and Suspense Audiobooks - March 17, 2025

- Africa Scene: Shadow City by Natalie Conyer - March 17, 2025

- The Ballad of the Great Value Boys by Ken Harris - February 15, 2025