BookTrib Spotlight: David Heska Wanbli Weiden

On an Indian Reservation, a Vigilante Seeks Justice

On South Dakota’s Rosebud Reservation, Virgil Wounded Horse waits for a man named Guv Yellowhawk. Yellowhawk has raped a nine-year-old girl, but her family knows there will be no official justice. Thanks to an 1885 law, tribal officers must pass most felony offenses to federal authorities, but “they didn’t mess with any crime short of murder…and the bad men knew this. When the legal system broke down, people came to me.”

Virgil Wounded Horse is a vigilante. “I’d waived my fee for this job. Usually I charged a hundred bucks for each tooth I knocked out and each bone I broke, but I decided to kick Guv’s ass for free.”

Unfortunately, this is an all-too-routine case for him. His next one will not be. A tribal councilman comes to him with disturbing reports of a major heroin operation on the reservation, and he wants it stopped. He offers Virgil five thousand dollars to track down the ringleader, a “mean drunk, thief, and liar” named Rick Crow and put an end to it: “Do what you have to do. Any means necessary.”

Something feels off about that to Virgil, and he says no, but when his nephew Nathan is pulled into it as well, he realizes he has no choice. To save him, to save himself, he hits the road with his ex-girlfriend Marie to hunt down Crow—but what he discovers is something much bigger than he ever could have imagined: an interlinking conspiracy that will make him question everything he thought he knew about himself, his family, his people, and what it means to be a Native American in the twenty-first century.

“I didn’t want to get up and face what I’d almost certainly lost. What I’d lost and still had to lose. The country of the living was gone to me, and I knew I’d entered a different space, one that offered no solace but only the wind and the cold and the frost. Winter counts. This was the winter of my sorrow, one I had tried to elude but which had come for me with a terrible cruelty.”

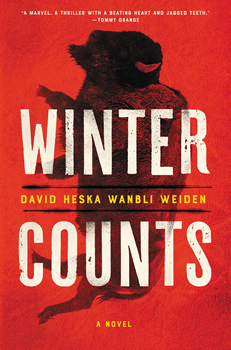

WINTER COUNTS is a remarkable, propulsive crime thriller filled with rich characters, a vivid sense of place, and big questions about identity, race, culture, and violence. It not only draws you into its own complex, haunting world—it makes you look at your own in an entirely new way.

David Heska Wanbli Weiden is an enrolled member of the Sicangu Lakota nation, a professor of Native American studies and political science at Metropolitan State University of Denver, the fiction editor of Anomaly, a journal of international literature and arts, and a writing teacher at the Lighthouse Writers Workshop in Denver.

“I’ve long been aware of the existence of Native enforcers on reservations, and I was always fascinated by these guys. For example, did they feel any remorse or guilt after they beat someone up? Or did they feel that justice had been served? So, I wrote a short story—also titled ‘Winter Counts’—way back in 2011, and it was published in Yellow Medicine Review in 2014,” he says. “I liked the story, but it stayed with me, and I began to feel that I hadn’t fully explored the character of Virgil Wounded Horse, the protagonist. So I decided to try my hand at expanding the story into a novel. Of course, I had to resurrect Virgil, as he dies at the end of the short story!

“But the real genesis for the book was my awareness—as a professor of Native American studies—of the absolute disgrace that is the criminal justice system on Indian reservations. It’s a complicated issue, but the short version is that there’s a federal law, the Major Crimes Act, that prevents Native nations from prosecuting most felony crimes that occur on their own territory. Instead, when tribal police have apprehended an offender, they must contact federal investigators and turn the arrested person over to them for prosecution. However, statistics from the US government show that around half of all felony cases are declined by the feds. So the criminal is released and is then free to offend again. Because of this situation, the victims’ families often turn to private vigilantes to get justice. As I describe in the book, the going rate is one hundred dollars for each bone broken and each tooth knocked out. These enforcers do exist in real life, although there’s no way to know how many of them there are.

“I’m often asked if I approve of the role of these private enforcers. No, my hope is that the federal government will begin adequately funding law enforcement and corrections on Native reservations, and that the Major Crimes Act will be amended or overturned. I believe that sovereign Native nations have the right to determine their own laws and sanctions in accordance with the principles of indigenous justice. My fervent wish is that WINTER COUNTS sparks a dialogue about the injustices occurring on Native nations because of the broken criminal justice system, and that policymakers will finally take some action to improve the lives of Native Americans.”

One of the central themes of the book is Virgil Wounded Horse’s struggles with his Native identity and Lakota values. He’s very bitter to begin with—as a boy, he tried to pray away his dad’s cancer and came back only to find him dead: “I knew then that the Native traditions—the ceremonies, prayers, teachings—were horseshit…I vowed that I’d never be tricked again by these empty rituals. From that moment on, I’d rely upon myself only.”

Did Wieden ever feel any of this himself?

“Yes, very much so. I grew up in Denver but visited the reservation frequently as a child, and I always felt like an outsider—never quite fitting in, both on the reservation and in the city. My mother did her best to instill Lakota values in me, but I often rebelled against them in my teenage years. I tapped into those feelings, of course, when I wrote both Virgil’s and Nathan’s characters. Now, I’m the father of two teenage boys, and I’m struggling to raise them in the Native way. I used this experience as well to write Virgil’s difficulties raising Nathan as well as his deep love for the boy.

“Most of the book comes from my own experiences and knowledge, although I frequently called family members still living on the reservation to make sure I was using the correct slang terms. For the Lakota language used in the book, I relied upon several faculty members at Sinte Gleska University in South Dakota. They were tremendously kind in correcting my many errors.

“I did a fair amount of research for the section on heroin, and how the distribution model is changing. I primarily relied upon the wonderful book, Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic, by Sam Quinones. That book was revelatory, and I strongly recommend it for those who haven’t been fortunate enough to read it yet. I was astonished to learn about the new heroin cartels and the ways in which they’ve revolutionized the sale of black tar heroin in part of the US. Heroin is a growing problem on many reservations, although meth remains the most pervasive scourge. Naturally, there’s a strong anti-drug message in WINTER COUNTS, and I hope the book opens eyes about this growing menace on reservations.”

He also had other influences. “As a kid, I was an obsessive reader and loved genre fiction,” Wieden says. “Mystery, science fiction, horror—anything that told a great story and kept me glued to the page. In college, I drifted away from genre and began reading literary fiction nearly exclusively: Updike, Carver, Cheever, DeLillo. I always loved Louise Erdrich’s books as well as other Native writers. The return to genre fiction for me came when I read Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove. That book absolutely blew me away, and I realized that a writer could tell a great story while developing complex characters and exploring challenging themes. I’ve also been influenced by some current writers, like T. C. Boyle, Benjamin Percy, C. J. Box, and Craig Johnson. Recently, I’ve had the good fortune to read the work of Attica Locke, Steph Cha, Lou Berney, Jim McLauglin, Brandon Hobson, and Stephen Graham Jones.”

He brought all of that into his work. “I like to build in certain image patterns, symbols, and allusions to other writers. For example, there’s an homage to the Native writer Louis Owens in the book, as well as to one other well-known crime writer. Writing voice and rhythm in an authentic and unique way can be a struggle. I try to channel my characters’ worldview, mannerisms, and style into distinctive cadences, and there’s no substitute for listening to the way people actually speak and converse in the community you’re describing. Virgil is a rough guy, and I worked to create a voice that reflected this.”

One of the things that helped him greatly in creating that voice was the strong support he gained from the writing community while he was working on the book. He was a MacDowell Colony Fellow, a Ragdale Foundation resident, a Tin House Scholar, and received the PEN/America Writing for Justice Fellowship. One of those experiences stood out in particular.

“They were all wonderful. But my time at the MacDowell Colony in 2018 was truly special,” Wieden says. “That summer, I was stuck in my writing process; I couldn’t find an ending for WINTER COUNTS that worked. I arrived at MacDowell and experienced an astonishing burst of creativity. The solitude at MacDowell—no Internet or television—was just what I needed. I wrote the ending to the novel in about three weeks and then had time to write a new essay about my grandmother’s time at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. I highly recommend writing residencies—the chance to work, uninterrupted, as well as commune with other artists is amazing.”

It also helped him take his next step. “I had the book about halfway finished in 2018, and I decided to take part in the AWP Writer to Agent program at their national conference. Given that I didn’t have a completed manuscript, I didn’t hold out much hope for obtaining a literary agent. However, I interviewed with the wonderful Michelle Brower of Aevitas Creative Management at the conference, and she signed me on the spot. I finished the manuscript about six months later, and we went out on submission. I was very impressed with Ecco and had a great discussion with Zachary Wagman, who’s now at Flatiron. Ecco made us an offer, and I was delighted to accept. They’ve been great to work with at every step.”

One other notable experience: writing a completely different kind of book—a middle-grade biography of a famous Lakota leader named Spotted Tail.

“Because it’s a biography, I endeavored mightily to make sure I had the facts of Chief Spotted Tail’s life correct,” Wieden says. “At the same time, I had to write the book in an age-appropriate style. It was a great experience to write that book, but I still prefer the complete freedom of fiction. I should note that Spotted Tail has gotten a great reception from Native families. I do not receive any royalties from that book, but instead purchased a large number of copies at my own expense. I’ve sent free copies to every elementary school on all of the Lakota reservations, and it’s been so gratifying to hear from teachers and parents that their children loved the book.”

WINTER COUNTS has already been greeted by remarkable praise from a wide variety of writers—from such crucial voices as Tommy Orange and Louise Erdrich to crime writers of the likes of C. J. Box, Lou Berney, and Craig Johnson. So what’s next?

“I’m delighted to report that there will be a sequel to WINTER COUNTS,” Wieden says. “I’m currently writing it now, and I can tell you that there will be some surprises for the characters. Also in the works is a collection of essays about the Native American experience, with a focus on my family and their travails. I have one essay completed (with the gracious support of PEN America) about my first cousin, who lived on the Rosebud Reservation with his mother and brother. When he was 17, he murdered both of them and stole a car, intending to drive to Colorado—to kill me and my mother. I was only two years old at the time. Luckily for me, he was arrested in Oklahoma and convicted of first-degree murder. I use this experience to examine the mass incarceration of Natives today in the federal prison system.”

And Wieden has one more thing to add: “I just want to say it’s an amazing time now for the thriller/crime fiction community. There are so many emerging writers who are telling stories in a new way and from new perspectives. For some reason, Native American writers have often shied away from writing crime fiction (although there are some great Native writers who have worked in this genre, most recently Marie Rendon and her excellent book Girl Gone Missing). I’m really hoping to read much more crime fiction from emerging Native writers. There are nearly 600 Native nations in the United States, each with a different history and perspective, and I hope their stories get told.”

*****

Neil Nyren retired at the end of 2017 as the executive VP, associate publisher and editor in chief of G. P. Putnam’s Sons. He is the winner of the 2017 Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Among his authors of crime and suspense were Clive Cussler, Ken Follett, C. J. Box, John Sandford, Robert Crais, Jack Higgins, W. E. B. Griffin, Frederick Forsyth, Randy Wayne White, Alex Berenson, Ace Atkins, and Carol O’Connell. He also worked with such writers as Tom Clancy, Patricia Cornwell, Daniel Silva, Martha Grimes, Ed McBain, Carl Hiaasen, and Jonathan Kellerman.

He is currently writing a monthly publishing column for the MWA newsletter The Third Degree, as well as a regular ITW-sponsored series on debut thriller authors for BookTrib.com, and is an editor at large for CrimeReads.

This column originally ran on Booktrib, where writers and readers meet:

- The Big Thrill Recommends: ORIGIN STORY by A.M. Adair - November 21, 2024

- Deadly Revenge by Patricia Bradley - November 21, 2024

- Unforgotten by Shelley Shepard Gray - November 21, 2024