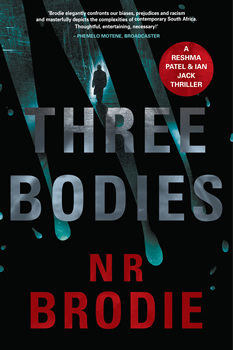

Africa Scene: Nechama Brodie

A Gripping Fusion of Police Procedural and Thriller

Nechama Brodie has worked as a journalist, editor, and publisher for nearly 25 years. During this time she’s dodged the secret police in Burma, explored tunnels underneath Johannesburg, gotten dusty at rock festivals, and reported on the myth of “white genocide” in South Africa. She has a PhD in journalism and gives lectures at the University of the Witwatersrand’s School of Journalism and Media Studies.

Brodie has authored and co-authored a number of successful nonfiction works, including the critically acclaimed The Joburg Book, a contemporary history of the city; Inside Johannesburg; and The Cape Town Book. Her first novel featuring Captain Reshma Patel of the South African police and her partner, Ian Jack—a supernatural thriller called Knucklebone—was longlisted for the Barry Ronge Prize and shortlisted for the Nommo Award.

The sequel, THREE BODIES, is a gripping fusion of police procedural and thriller with a supernatural twist. The body of a woman is found caught in the waterweed of Hartebeespoort Dam on an upmarket golf estate, but no one seems to have a record of her entering through the estate’s tight security. Ian is asked to investigate.

Meanwhile, Reshma makes a grisly find in the abandoned tunnels under Johannesburg’s Park Station that turns out to be related to cash-in-transit heists near the city. Then she discovers that two other women have been found dead in rivers. She and Ian enlist the help of a sangoma, or healer, named MaRejoice, and together they have to discover the link between the murders of the women and the heists, and why the bodies all ended up in water.

In this interview with The Big Thrill, Brodie gives insight into her new release and shares how she made the bridge to writing crime fiction.

You have a PhD and a successful career as a journalist, and you’ve just completed a major nonfiction work on violent crime against women in South Africa. What persuaded you to start writing crime fiction?

I’ve always been a reader of crime fiction—my mother used to read true crime, but I discovered I was more partial to thrillers and detective stories (I also read a lot of science fiction and fantasy). This ranges from childhood mysteries (Alfred Hitchcock and the Three Investigators) to the classics (Sherlock Holmes, Agatha Christie), the good early noir (Spillane, Hammett), and then more contemporary crime writers like Sara Paretsky, Michael Connelly, and so on. So it’s a well-known field for me. When you marry that with my real-life academic work researching real crime and my multiple nonfiction works, it was kind of a natural segue. A lot of crime writers come from a crimefighting background (former prosecutors and so on). I think writing crime fiction represents a desire to find the “justice” we don’t always see in the real world.

THREE BODIES is set against the backstory of the rash of cash-in-transit heists in South Africa, especially in Johannesburg. The robbers stop at nothing to loot the vehicles, even setting them alight with the guards inside. How did you research these crimes and the police units that try to stop them?

I combined extensive research of media archives and news stories with Anneliese Burgess’s brilliant investigative book Heist. I also watched every single online video I could find that showed a heist in progress or the aftermath, so I could get a sense of how it sounded and played out in real time. The imagined horrors are sadly not that far off the truth: the CIT heists can be particularly brutal, and the criminals that commit them are utterly ruthless. Watching videos of the robberies is quite startling. These crimes are committed with such impunity. There is also a very strong link between these crimes and traditional beliefs. Many heist criminals look for supernatural or magic protection. So there was a logical and easy link between that and my characters’ close relationships with sangomas and traditional beliefs.

Traditional African beliefs play a major role in your novels. Would you tell us about your experience with them? THREE BODIES pivots on “mermaids,” but certainly not the fish-tailed charmers of fairy tales. Where did they come from?

African water spirits are very traditional, and much older than many of us realize (i.e. they have nothing to do with Northern “mermaid” myths and weren’t imported). When I was writing my history of Cape Town (The Cape Town Book) I read stories about the princess that was rumoured to haunt the waters of the Princess Vlei. There are stories about water spirits in the rivers of the Karoo. There are mermaid-type legends all over Africa. The spirits mean and represent different things to different people, and they are also shrouded in secrecy. I wasn’t able to access any real deep dark truths about these figures, so a lot of what I wrote was intuition and imagination, and also a lot of respect for what are very powerful entities.

Reshma Patel is a career policewoman who breathes efficiency and commitment to the point where it endangers her personal relationships. You’ve mentioned that the police in South Africa face a challenging job in difficult circumstances, but, while the public sees only corruption and inefficiency, many do great work. Was this the basis for Reshma’s character?

It’s so easy to mock the police service without understanding what they are exposed to, day in and day out. They’re not earning vast salaries, sitting in an office with a [potted] plant and a nice view. Most officers are underpaid, undersupported, sometimes even reviled—and yet they go to work every day, often putting their lives on the line to do their jobs. I like to believe that the reason they do this is because they believe in what they do, and they want to help—that they are, in the majority, invested in our safety and security.

When I was working on my PhD, I would sometimes (not often, but often enough) come across stories that reported on the efforts of the police officers who had brought a criminal to justice—my work was on femicide, so these were stories of how they had caught murderers, the painstaking investigations, arrests, court cases. Justice is not always swift, and sometimes these cases would take years. Many cases would just be forgotten. But there were a handful that were not, where officers had worked on the slenderest of leads for three, four, five years even, and eventually they would catch the guy. I wanted Reshma to have those attributes: to believe that what she does is part of the justice process. Ian believes he is too, but he’s a lot less rule-bound. Reshma is often the one who gets caught up in bureaucracy, who worries about hierarchies and chain of command. She’s ambitious and hates it when her superiors see her stepping outside the lines. But she’s also not afraid to do what needs to be done, when it comes down to the wire. I like to believe that, in difficult circumstances and given the choice, most of our police officers would do the right thing.

Reshma’s partner Ian, who is evidently missing his previous life in the police, plays a somewhat subsidiary role in this book. He’s more sympathetic to the supernatural than she is, and while both experience certain phenomena, he is the bridge. Is this a case of “I don’t believe it, but it is true”?

Ian isn’t just sympathetic. He believes it. He’s seen too much not to. He just can’t quite reconcile it with his own life, his upbringing, so he feels like an outsider and he’s comfortable with that status. He’s not trying to become a sangoma.

Reshma is the cynic. She’s seen many of the same things that Ian has, but she will always look for a rational explanation even when there isn’t a good one. But, increasingly, she’s learning to become less dismissive of other people who believe or see what she cannot and does not. In my first book, Knucklebone, Reshma is initially very dismissive of MaRejoice. By this time, though, they are reluctant colleagues.

Most South African crime fiction is set in the Cape or in the wilds of the South African bush, much less in Johannesburg. Yet Johannesburg is the country’s biggest, economically most important, and anecdotally most violent city. You have written a book about Johannesburg’s history. Did you set out to make the city a character in your novels?

Johannesburg was a central character in my first novel, Knucklebone. The story really stalked the city’s streets in that book, and I imagined it very vividly in the locations where the scenes took place—particularly the (for me) constant edge of potential horror in the suburbs, and the rough industrial intensity of City & Suburban. I think it’s also because when I wrote the book, I was spending a lot of time in the city and was immersed in those narratives.

In this book geography still plays a leading role but it’s no longer only about Joburg (although once again, the city center’s frayed edges get a supporting role). The starting point for me for this book was really the Hartbeespoort Dam—it’s also such a contested (man-made) space: the invasive water hyacinth, the pollution, the fancy golf estates on the one hand and poverty on the other… It’s a metaphor for so many things in South Africa. I like that about space and place.

This is the second mystery featuring Reshma Patel and Ian Jack. Are you planning more in the series?

This was a sequel by accident—my previous agent asked me if I had planned a series, so I made up a plot idea on the spot and submitted it. Now I guess it depends on whether or not there’s a market for more Reshma and Ian stories. I do have another mystery brewing. If enough readers buy these books then there’s a good chance there will be a third. I’m a pragmatic writer, and it’s also about what sells as much as what stories live in my head. I’m working on other fiction works that aren’t Ian and Reshma books too, so we’ll see…

- Out of Africa: Annamaria Alfieri by Michael Sears - November 19, 2024

- Africa Scene: Abi Daré by Michael Sears - October 4, 2024

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024