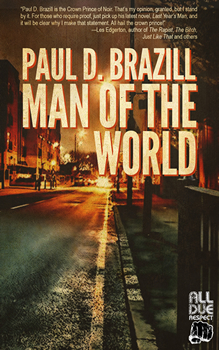

Man of the World by Paul D. Brazill

By Tim O’Mara

Paul Brazill’s newest novella, MAN OF THE WORLD, features aging hitman Tommy Bennett, who has left London and returned to his coastal hometown, hoping for a peaceful retirement. It isn’t long before his past catches up with him, sending him running back to London—only to find that mayhem awaits him there as well.

I asked Brazill if it’s really possible for someone who’s made a living as violently as Tommy has, to ever retire.

“Tommy Bennett is an archetype, really,” Brazill said. “He’s like the Western gunslinger trying to hang up his Colt .45: a man who has done bad things and has started to doubt himself.

“I think all of us have problems leaving the past behind,” Brazill continued, “and violence casts a longer shadow than most. Also, I think violence is highly addictive, like all adrenaline boosts. When I lived in London in the ’90s, I knew someone who used to be a member of the Richardson Gang—AKA the Torture Gang—in the 1960s, and he was completely haunted by his violent past, even as an old man. He’d stopped drinking after an accident and the truth of the person he was almost crushed him. You are what you do, after all.”

In the novella, Tommy is quoted as saying, “Hope is the opiate of the masses.” Considering the current situation the world finds itself in, I asked Brazill to elaborate.

“Well,” he said, “there is no way that the characters in MAN OF THE WORLD are going to be open to cheap optimism. They’re not going to buy a lottery ticket if they want to get rich. They are, after all, men and women of the world. They’ve been around the block and see life as a case of damage limitation. It’s not about getting dealt the best hand of cards but playing a bad hand well.

“That said, I think most of us are hoping for a happy ending [to the current crisis] even if it’s far from likely. Placebos can be very effective.”

Once again, Brazill has written a book with an antihero who’s more aware of the music around him than most folks. Does Brazill listen to music while writing? What music has influenced his writing and maybe even given him ideas for his books?

“Both Tommy and I are men of an uncertain age,” Brazill told me. “We grew up at a time when music was everywhere in the UK, and it was very important to young people, too. The ’60s and the ’70s were formative years. I doubt Tommy has such an attachment to modern music, though. I think music taste can also show how stunted the characters in a story are. It shows their age, like a receding hairline.

“There was a time when I could only listen to instrumental music while writing—jazz, film soundtracks. But now it helps with the pace. I’ve certainly stolen a lot of titles from songs, though they’re not always directly linked.”

I asked Brazill to talk a bit about the art of the novella as compared to a full-length novel or short story. Also, I pointed out that not many publishers are releasing novellas…

“Oh, I really don’t know why they’re not [more] popular,” Brazill said. “I love them! Though, apparently, Don Winslow is doing novellas now so that may change. For me, the novella is just the right length to tell a story without getting bogged down with exposition, soap opera, and holding the reader’s hand—without needless repetition and hammering home the point. A good novella is a short, sharp shock. Fast and furious.” And just to punctuate the point about music, Brazill added that novellas are “more like a Ramones single than a Genesis LP.”

It’s worth noting that Brazill’s publisher, Down & Out Books, doesn’t share the industry’s aversion to shorter books. “Novellas make for a change of pace,” says the house’s associate editor, Lance Wright. “Shorter, usually by at least half, than a typical novel, they can be read and enjoyed in half the time. And with all of us so busy with endless to-do lists, it’s good to have the option of reading (and completing) a book relatively quickly. Too, novellas are typically paced a little faster than a novel, making them perfect for readers who often have limited time to read but want the story to move along at their pace—think commuters on a train or people traveling by plane from one city to another.”

Brazill’s books have been translated into Italian, Polish, Slovene, German, and Finnish. I wondered if he was concerned that something was literally going to be lost in translation?

“Oh, I’m sure lots of stuff is lost in translation,” he said. “Some things just can’t be translated literally and have to be completely rewritten. When I lived in Warsaw, I worked as a proofreader on translated subtitles for some Polish documentaries, including [the work of renowned Polish filmmaker Krzysztof] Kieślowski. A lot of that really couldn’t be translated directly, though it hadn’t stopped the previous translator trying, and failing!

“To be honest, I think once you hand something over to a translator, the finished product is their work. Like a cover version of a song, or a film or TV adaptation of a book. Sometimes they can be just as good as the original, or even better. John Coltrane’s version of ‘My Favorite Things’ is the consummate version and Netflix’s recent Manchester, England-set adaptation of Harlan Coben’s The Stranger was great and very much its own thing.”

Speaking of European TV crime dramas, I told Brazill I had just watched The Mire from Poland (where Brazill currently resides) on Netflix. I asked him to comment on the difference between American TV crime dramas and European ones.

“I haven’t seen The Mire,” he told me, “but I’ll check it out. Recent Polish TV crime series seem to be inspired by the Nordic shows in their execution. Accordingly, they can be a tad grim and too humorless for my tastes. The best American and British TV shows, like Fargo, Better Call Saul, and The Stranger, have a sense of the absurd about them, which actually makes them more realistic. Sometimes I think some of those misery-guts Scandinavian detectives just need a good sh…shake!”

In these new and strange times we’re living in, I couldn’t agree more. Well-written crime stories just might be the good shake we all need.

*****

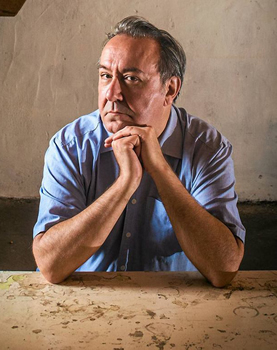

Paul D. Brazill’s books include Last Year’s Man, Gumshoe Blues, and Kill Me Quick. He was born in England and lives in Poland. His writing has been translated into Italian, Finnish, Polish, German, and Slovene. He has had writing published in various magazines and anthologies, including The Mammoth Books of Best British Crime.

To learn more about the author and his work, please visit his website.

- Wealth Management by Edward Zuckerman - September 30, 2022

- Homeland Insecurity by J.L. Abramo - August 1, 2022

- Unruly Son by Neil S. Plakcy - May 31, 2022