Africa Scene: Leye Adenle

Delving into Corruption in

the Nigerian Political Landscape

Nigerian writer Leye Adenle’s debut Easy Motion Tourist, set in Lagos, earned critical acclaim and inspired reader enthusiasm. The Guardian called it “Fast and furious … a roller coaster ride through a world of extremes, where everything is up for grabs.” The novel went on to win the 2016 Prix Marianne.

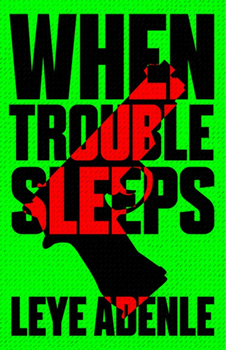

Now, Adenle follows it up with WHEN TROUBLE SLEEPS, a continuation of his Lagos crime series featuring social activist Amaka Mbadiwe. The Guardian has already chosen this political and social thriller as one of the best recent crime novels, and thriller master Lee Child summed it up with the following praise: “Spectacular—Adenle is crime fiction’s best new voice for years.”

Adenle took time out of his schedule to chat with The Big Thrill about WHEN TROUBLE SLEEPS.

Amaka is a strong protagonist—independent, self-assured, smart. Yet, she has great empathy for her work, trying to protect prostitutes from malfeasance rather than “rescuing” them from a lifestyle when they have no other real option. Did you set out to develop a female protagonist, or did Amaka develop from the role you wanted her to play?

When I think of it, the story came with its own protagonist. I’m tempted to say the story came first, and through the writing, the Amaka character evolved, but I can’t really see it that clearly: where the idea ends and where Amaka starts. Recently, while talking about how the idea for the story came from a conversation with my mum and her lifelong work and concern for the wellbeing of young women in Nigeria, I had an epiphany: I know who inspired Amaka.

While Easy Motion Tourist focused on prostitution and Amaka’s efforts to support the women caught up in it, WHEN TROUBLE SLEEPS is about political corruption. This time Amaka must somehow prevent a corrupt and disgustingly lecherous man from becoming governor of Lagos. The picture you paint of opposing party bosses working to rig the election and get their hands on public funds is a discouraging one. Is this how politics actually works in Nigeria?

Corrupt and disgustingly lecherous men are often found at the highest levels of government, and when it comes to elections, opposing parties smear opponents with lies, put out fake news, and rig the election itself just so they can be in position to award contracts to their friends, give tax cuts to cronies…and that’s just in America. Sadly, Nigeria does not fare better. A former president of Nigeria once described it as a “Do or die affair.” Unfortunately his words are an accurate and objective description of electioneering in Nigeria.

Amaka has her work cut out for her because she also wants to close down The Harem, a debauched brothel in the forest outside the city, and take down its owner, Malik. Although there are some pretty nasty villains in the story, Malik is probably the nastiest. He thinks nothing of killing and torturing the girls who cross him and laughs in the faces of policemen. How did you conceive him?

Malik was an accident. I had written the first book and submitted it to my publisher when my editor suggested I write a prologue. I don’t like prologues (and I still don’t—which is why everyone dies in the prologue of the new book) but I trusted my editor, and so I wrote one to introduce the world of the novel, and that world, it turned out, belonged to Malik. While his clients represent one side of the abuse and exploitation, and the girls represent the abused, he is the natural embodiment of the vilest of the vile who profit from the abuse.

Police inspector Ibrahim is a complex character, not at all the usual cop. He’s willing to take the law into his own hands and clearly likes Amaka (to the extent of lending her his car at one point). How did you research the spectrum of the police detectives in Lagos to make him believable?

I’ve had plenty of dealings with the Nigerian police, from checkpoints in the middle of the road at night to officers behind desks in police stations. Bar Beach police station and the headquarters at Panti are both places I’ve had reason to visit often, and at the time not because I was doing research. I wasn’t in trouble either—at least not directly—but some people were, and some people needed serious police work to be done. I guess in a way my research started long before it did. I guess I was writing about things I knew of, firsthand.

I also have friends in the police, including a police boss I’ve never met, but whose number I have (had), and who I sometimes called to get out of sticky situations or to help friends get out of sticky situations. By sticky I mean situations where the police needed convincing to do their job, or situations in which the bribe demanded for a debatable minor traffic offence needed to be waived, or at least negotiated down.

In the apartheid days in South Africa, government informers (or anyone thought to be a government informer, or for that matter anyone maliciously denounced as a government informer) risked being necklaced—having a tire full of gasoline thrust over his head and set alight. Amaka meets this in modern-day Lagos, as well as people taking the law into their own hands. Is this practice common, and is it motivated by a lack of confidence that the police will do anything?

In the case of Nigeria, I do not think it has to do with lack of confidence in the police. There are even videos that seem to show police officers “allowing” such lynching to go ahead. I must say that there are also many recorded instances when the police have rescued victims from such killer mobs.

I almost made the entire book about the topic. I wanted to talk about the kind of jungle justice that results in such a disturbing thing happening still today, and not just in Nigeria. Taking justice into one’s own hands should never, ever, result in taking a life, no matter what. There are questions that need to be asked. What is the state of mind of the people who take part in such public lynching? Even the complicit people who watch. What deep societal traumas have made it possible for them to be that way?

The book has a great action climax with twisty final scenes with Malik, and with a woman Amaka has been trying to help to bring her brother’s murderer to justice. It shows crime and punishment in Lagos in a very different light from, say, London. Yet it’s quite satisfying to the reader. Would you comment?

Sometimes justice is done and seen to be done, sometimes justice is not enough, and sometimes not even revenge is good enough. To be the one in need of justice is a deeply personal thing that can only be resolved in a personal way. We empathize with the woman Amaka is seeking justice for, and when the woman chooses her own resolution, we understand that it is what she needs—it is her justice, not ours, and for her, it’s what she needs.

At the end of WHEN TROUBLE SLEEPS, Amaka is on the way to London to link up with her boyfriend, Guy. Perhaps her next adventure will take place there?

I want to set future books in the series in London, Paris, Accra, Cape Town, even Kiev, but not the next book, as it’s already on its third draft and it’s very much of the Naija Noir flavor of the Sunshine Noir genre.

- Out of Africa: Annamaria Alfieri by Michael Sears - November 19, 2024

- Africa Scene: Abi Daré by Michael Sears - October 4, 2024

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024