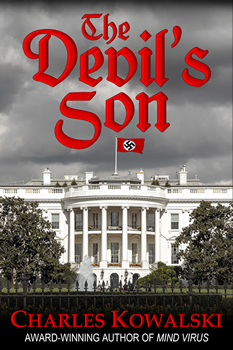

The Devil’s Son by Charles Kowalski

By Azam Gill

By Azam Gill

The moral dilemmas that bind the suspense and action in Charles Kowalski’s THE DEVIL’S SON will keep the reader awake long into the night.

A United States Secret Service agent faces a conflict of interest between protecting the presidential candidate and respecting the findings of the Nuremberg Trial which upheld the call of conscience over blind obedience. Somehow, he must decide whether his professional commitment is an infinite moral value or subject to his conscience.

The agent has probable cause to believe that his principal is the son of a Nazi fugitive. It is unknown whether the candidate is repelled by or committed to his father’s affiliation. If elected president, is he liable to use his powers to protect his father? Or exonerate him? Or worse still, infiltrate neo-Nazis into the highest levels of the US government?

And then, to cap it all, the Secret Service agent meets a ravishing Israeli secret agent who is determined to stop the candidate from becoming president.

The classic enemy-within theme and inner-conflict management unfold at a brisk pace, prompting several of Charles Kowalski’s peers—such as Jeff Edwards, bestselling author of Sea of Shadows and Steel—to lavishly praised his debut novel, Mind Virus: “The kind of pulse-pounding, adrenaline-pumping thriller that I associate with the best of Clive Cussler and Ken Follett.”

Hardly surprising, then, that the novel went on to win the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers’ Colorado Gold Award, and was a finalist for the Killer Nashville Claymore Award and the Clive Cussler Grandmaster Award.

But THE DEVIL’S SON goes further than Mind Virus.

Kowalski’s research led him to delve into the inner workings and procedural drills of Israeli Intelligence and the U.S. Secret Service, uncovering unfrequented and dangerous paths.

“It was also instructive to learn about the motivation and philosophy of white identity extremists, and understand how a candidate like this one could use them to gain power,” he says. “And as I was in the final stages of writing it, I was surprised—and disturbed—by the parallels that were increasingly appearing between my book and the daily news headlines. As C. S. Lewis said, ‘The trouble with writing satire is that the real world always anticipates you.’”

Kowalski’s penmanship has contributed to the ascending status of the espionage thriller as a platform of moral comment. Sir Philip Sidney’s 16th century poetics, The Defence of Poesy, exhorts the ‘poet’ to entertain and instruct. Both tasks are accomplished in THE DEVIL’S SON, which raises the all-important question of why a defeated and bankrupt supremacist movement is able to survive and attract followers in a flourishing democracy.

The internal impulsion and external stimuli that lead to supremacist movements such as neo-nazism are still not fully understood. As such, the field remains fertile for skilled writers and movie makers.

Robert Ludlum, Frederic Forsyth, Hanif Kureishi, James Patterson and James Herbert are only a few among many who have dipped a toe in this area. Hollywood, too, has been busy, with American History X, Heart of a Lion, Steel Toes and Brotherhood, to name a few, hitting the big screen in the past few years.

To be able to exist at all, evil needs to hide within what is good. It was under the semantics of nationalism and socialism that Nazism prospered – all the way to the holocaust. Entertaining movies and books are a fine way for a few good plumes to provide the means of appreciating the ugly reality of evil.

As Kowalski’s writing does.

That ability also admits him into the illustrious company of thriller writers whose characters have to handle the intricacy of ethical choices and decisions which are well above their pay grade. As such, Kowalski has been compared to Dan Brown.

Fortunate considering that both Dan Brown and Dan Da Silva have inspired Kowalski to craft thrillers that direct the reader’s focus to the illusion and reality of religious organizations, as in Mind Virus.

Kowalski “admires” Barry Eisler and Barry Lancet and, in common with them, his characters and writing career started in Japan before moving on to “encompass the world.”

A black belt in Shorinji Kempo, a modern offshoot of Kung Fu, he watches movies when he can and thinks of how he would have written them differently. After studying Classics and East Asian Studies at Oberlin College, he qualified in Japanese pedagogy at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, and completed a Master’s in English and Spanish pedagogy at SIT Graduate Institute in Vermont. He now teaches English at a Japanese university.

Although Kowalski is a dedicated writer independent of his surroundings, it is not at the expense of his family life. How and why he writes is best described in his own words.

“Like many writers, I start with a ‘What if…?’ question, then develop the characters and storyline,” he says. “I’m a ‘plotter’—I can’t sit down to start a story unless I have some idea of where it will end and how I’ll get there – though of course it never goes exactly as planned!

“Being a writer has been a dream of mine for as long as I can remember. When I was a child, I loved reading stories, and that naturally led to writing them. What ultimately motivated me to seek publication was 50% inspiration and 50% desperation: I had ideas for stories, and saw writing as a way to maintain a connection with my home country during my long years of self-imposed exile.”

Kowalski is almost as much of a global citizen as his fictional hero, Robin Fox, having lived abroad for over 20 years and studied over 10 languages. He now divides his time between Japan and Downeast Maine.

*****

Charles Kowalski’s debut thriller, MIND VIRUS (Denver: Literary Wanderlust, 2017), won the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers’ Colorado Gold Award, and was a finalist for the Killer Nashville Claymore Award and the Clive Cussler Grandmaster Award.

Charles Kowalski’s debut thriller, MIND VIRUS (Denver: Literary Wanderlust, 2017), won the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers’ Colorado Gold Award, and was a finalist for the Killer Nashville Claymore Award and the Clive Cussler Grandmaster Award.

To learn more about Charles, please visit his website.

- Dissection by Cristina LePort, MD - September 30, 2022

- Direct Legacy by James Stejskal - August 1, 2022

- Breaking Character by Mark T. Conard - May 2, 2022