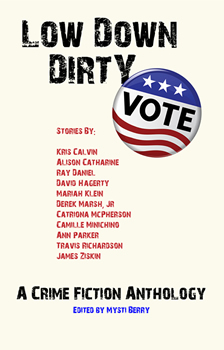

Low Down Dirty Vote by Mysti Berry

By Tim O’Mara

By Tim O’Mara

In case you somehow missed it—maybe you were up to your neck in your latest WIP—there’s a big election this year. (When’s the last time we had a “small” election?) It seems like every group out there is doing their level best to scream louder than the other groups. Go on Facebook—or don’t—and it’s hard to find a post that’s not pro-this or anti-that and why you should feel the same way. At times, it just feels like so much cocktail party opinionating. (I may have made that word up.)

In an attempt to cut through all this noise, Mysti Berry has compiled and edited a dozen or so crime stories about the voting process in the anthology LOW DOWN DIRTY VOTE. Many people may try to pigeonhole writers into a certain political group, but Berry doesn’t see it that way.

“It surprised me when people talked about LOW DOWN DIRTY VOTE as political,” she writes via email. “Voting is the most important tool a citizen has to affect change or keep something that doesn’t need to be fixed in the first place, no matter what change or stasis that person thinks is best. To me, specific policy positions are political: pro-this or anti-that. And I do think that writers, regardless of their feelings on certain policy issues, try to avoid preaching from the page. My goal was to get to (some) level of common understanding, not stand on an apple box and shout my policy positions to the world.”

I asked contributor Mariah Klein, whose story “Bombs Away” takes a closer look at voter intimidation, if her entry was based on a real-life occurrence.

“I was not inspired by a specific act of violence,” she explains, “but instead by news accounts of voter intimidation tactics and legislation that allow for legal and purportedly logical actions to be taken that have the effect of disenfranchising people of color, poor people, and voters who speak languages other than English.”

Klein goes on to quote a Trump supporter describing what he felt was his role in intimidating voters—especially those of color—during the voting process: “I’m going to go right up behind them. I’ll do everything legally. I want to see if they are accountable. I’m not going to do anything illegal. I’m going to make them a little bit nervous.”

As writers often say: You can’t make this stuff up.

Ann Parker’s story, “A Clean Sweep,” serves as a kind of history lesson about the pressures women were under when they first won the right to vote.

“The drive for suffrage for women in the US goes back to the very beginning of our nation,” Parker reminds us, “with Abigail Adams writing to her husband John Adams on March 31, 1776: ‘… in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could.’ ”

Parker then takes this historical moment and brings it into the more recent American kitchen. “The story I wrote was inspired by a chance comment from my grandfather, probably in the 1960s timeframe (when I was old enough to understand the ‘basics’ of voting, but still quite young), that my grandmother voted the way he told her to. That stuck with me, and I have to wonder what happens behind domestic closed doors now.”

Ray Daniel’s piece, “Beached,” is a humorous—yet not-so-humorous—story of how far some folks are willing to go to make sure certain groups don’t even make it to the polls. “While ‘Beached’ was not a copy of a real-life incident,” Daniel says, “it was inspired by the fallacy that there is such a thing as ‘those people’ and that ‘those people’ will always vote a certain way.”

The city of Chicago has a long-held—deserved?—reputation for voting shenanigans. David Hagerty’s story, “Chicago Style,” focuses on the Windy City and Election Day.

“While Chicago sets the standard for voter manipulation, this country has a long history of political chicanery—from gerrymandering to poll takes,” Hagerty says. “More recently, we’ve endured two elections decided by the Electoral College, Russian interference in our last presidential race, and the purging of legal voters after two years. Any time that money and power are at stake, the temptation to cheat the electorate will be strong.”

In “Absentee,” Alison Catharine makes the point that not everyone who can vote does, and some who want to can’t because of previous mistakes. “I don’t agree that someone’s past should disqualify them from voting,” she explains. “Clearly in the case of a convicted felon, there are laws that prohibit such individuals from voting. Although in some states (19, I believe) once any probationary period/supervised release has ended and two years have passed, voting rights are automatically re-established. Once all required laws are satisfied, I would hope everyone—including the story’s main character—would resume voting. It can be perceived as a return to being part of ‘normal society’ for such individuals. A homeless man I served on a jury with once was so excited to both do jury duty and vote for the first time. It was an acknowledgement for him of being ‘normal’ to do both. The rest of us were just trying to get out of jury duty and return to the office!”

Catriona McPherson takes a whole different view on voting. Her story, “Twelve, Angry,” has nothing to do with political elections, but does stress the concept of majority rule and has strong echoes of the #MeToo movement.

“The story was my way of saying—and I really do believe this—that to be enfranchised, as women were one hundred years ago this year in the UK, gives you more than a vote every election time,” she says. “I think the operation of democracy spreads out from the ballot box and can be a guiding principle in daily life. I’m a big fan of the Enlightenment.”

Travis Richardson’s “Another Statistic” takes a darker look at the voting process and today’s society. “Voter suppression sickens me,” Richardson says. “Growing up in the 1980s Reagan era, the patriotic rhetoric of the day said that a citizen’s ability to choose their leaders made the difference between communist dictators and democracy. Now that’s been forgotten with the ‘us vs. them’ mantra that started in the ’90s and has spiraled out of control into an awful divide, repress, and conquer strategy. It’s so un-American to the point of being nauseating.”

Rounding out the collection are stories by James Ziskin, Kris Calvin, Camille Minichino, and Derek Marsh, Jr.

At this point, it seems fitting to yield the floor and give the last word to LOW DOWN DIRTY VOTE’s editor.

“Each story is a unique take on all the things that happen when people’s votes are stolen from them, figuratively and literally,” Berry says. “The talented writers in this anthology created timeless, universal stories. Many of them feature plots relating to suffrage, which is totally understandable as 2018 is the 100th anniversary of the UK granting women the right to vote. The writers each tackled a story that challenged their skill with unique POVs, story structures, and wonderful characters acting out surprising events. I have a fan-crush on each and every one of the contributors.”

*****

The authors of Low Down Dirty Vote, Kris Calvin, Alison Catharine, Ray Daniel, David Hagerty, Mariah Klein, Derek Marsh, Jr, Catriona McPherson, Camille Minichino, Ann Parker, Travis Richardson and James Ziskin, live on both American coasts. Amongst them they have dozens of writing awards. From high-tech, education, journalism, and more, the backgrounds and worldview of these writers are as varied as America itself.

The authors of Low Down Dirty Vote, Kris Calvin, Alison Catharine, Ray Daniel, David Hagerty, Mariah Klein, Derek Marsh, Jr, Catriona McPherson, Camille Minichino, Ann Parker, Travis Richardson and James Ziskin, live on both American coasts. Amongst them they have dozens of writing awards. From high-tech, education, journalism, and more, the backgrounds and worldview of these writers are as varied as America itself.

The editor, Mysti Berry, has been published in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine and other anthologies. This is her first charity anthology.

To learn more, please visit the website.

- Wealth Management by Edward Zuckerman - September 30, 2022

- Homeland Insecurity by J.L. Abramo - August 1, 2022

- Unruly Son by Neil S. Plakcy - May 31, 2022