Between the Lines: Walter Mosley

Trying to Understand the World

Someone might assume that when Walter Mosley sits down to write a novel—after publishing more than 50 books and winning awards and fame for his art, not to mention those film adaptations—he’s able to manage polishing off a new book without any difficulty at all. But that wouldn’t quite be accurate.

“It’s not a novel unless it’s bigger than your head,” Mosley says. “While you’re working on a novel, it’s so hard for you to know all the stuff about it, but the minute you begin to believe you do know everything, that’s the time when the novel stops being a novel and becomes a plot or a storyboard.”

If you’re wondering if that means Mosley writes his books without a detailed outline first, the answer would be yes. “There is an unconscious agenda reaching through you to write that book,” he says. “It’s not like a blueprint for a new building, because you have to have that or else the building will fall down. This is about human emotions.”

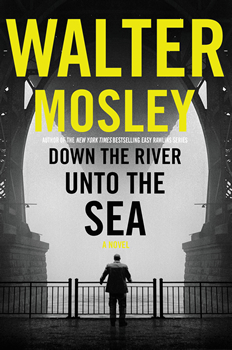

In his new novel DOWN THE RIVER UNTO THE SEA, Mosley has crafted characters of profound emotion. Joe King, the protagonist, is a top-notch black police detective who encounters a moment of temptation and falls. It’s so spectacular a fall that King finds himself in Rikers Island Jail, beaten and broken. Years later, as a private detective, King discovers the agenda behind his disgrace, and sets out to find justice, and redemption, with the help of some of New York City’s outlaws.

Mosley’s moment of inspiration for writing the book is an audacious idea that can’t be revealed because it comes at the end. “The reason I wrote the book has to do with the ending. In order to do that, I had to create the characters who would bring me there.”

Perhaps the most memorable of the secondary characters is an utterly ruthless criminal, wise to the way of the streets, named Mel. Mosley says, “The more I think about the world we live in, the more I understand how what used to be seen as mental disabilities are actually really helpful for survival in this world. Like an obsessive compulsive who is really good at being an accountant or a scientist. Or a person without any kind of moral diagram by which he can live life—therefore he can break the rules and do the things he needs to do in order to survive. The sociopath. Mel.”

The novel deals with issues of morality and trust, and it’s set in a tense New York of police, lawyers, politicians, and criminals, but is full of universal truths as well. That’s not an accident. “When you’re writing a novel, you’re trying to understand the world,” he says.

One thing that Mosley is grappling with in the novel is the power of money. At a critical juncture in the book, King, the narrator, says, “A man can live his whole life following the rules set down by happenstance and the cash-coated bait of security-cossetted morality; an entire lifetime and in the end he wouldn’t have done one thing to be proud of.”

There’s unquestionably a statement about Wall Street values in that passage: “You have to be up 20 hours a day, stacking money,” as Mosley puts it. But there’s more. Turning his attention from financiers to publishers and the value of money in how an author sees himself or herself, Mosley says, “The definition of success often becomes monetary. I’ve read that Faulkner, when a book first came out, it never sold more than 3,000 copies. While you could be Faulkner and say, ‘I’m not important because I don’t sell as many books as Mickey Spillane.’ Mickey once had nine of the 10 bestsellers of the year. And Mickey Spillane is pretty much forgotten. Faulkner will never be forgotten.”

While Mosley was talking on the phone about writing, he was staying in Los Angeles, working on an episode in John Singleton’s dramatic series Snowfall. He enjoys the fun and collaborative spirit of writing for television but has a particular thought about the “Golden Age” of television that some people hail in the press.

“The only problem I have is that the other day a big-time critic said, ‘Television is the new literature’,” Mosley said. “A lot of people think like that. Look, when you’re watching television, you’re really passive, that’s why you do it, you want to relax. There’s no comparison between reading anything and watching television. So when people try to move it beyond where it is—yes, TV is artistic and philosophical and you can do character development and wonderful things with a camera, and yes, it’s gorgeous. But if you want to develop your mind, you want to be reading.”

As Mosley says, “When you find a writer who really speaks to you, you take it in on all kinds of levels.”

It’s in reading that an individual relationship is formed between reader and novelist, in experiencing the work. “The words come into your brain and your brain becomes aggressive,” he explains. “Your brain grabs the words and tries to come to an understanding with them. While with television, it tells you what you’re seeing. Here’s a naked woman. Here’s a man with a gun. It’s different.”

Mosley has said, “Writing a novel is gathering smoke; it’s an excursion into the ether of ideas.” Moreover, he believes strongly that any novelist can grow in craft through writing every morning—anyone can gather the smoke. “You get deeper and deeper into yourself, and as you get deeper, certain images come up.” Mosley wrote the nonfiction book This Year You Write Your Novel, published in 2009.

He has many projects going, among them a novel coming out this fall with Atlantic Grove about a deconstructionist historian. But nothing changes one essential. “When people say, ‘What’s the best thing about your career as a writer?’ I say, ‘Waking up in the morning and writing for three hours.’ That’s what I do.”

“Everything is writing,” says Walter Mosley. “No one has replaced the discipline of writing or the value.”

- Up Close: Kris Waldherr - September 30, 2022

- Up Close: Wendy Webb by Nancy Bilyeau - October 31, 2018

- Between the Lines: J. D. Barker - September 30, 2018