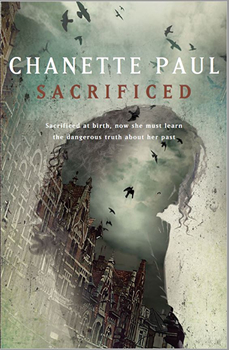

African Scene: Chanette Paul

A Character Both Strong and Vulnerable

Chanette Paul is one of South Africa’s most prolific Afrikaans authors, having written more than 40 books that span several subgenres. She was born in Johannesburg but has traveled widely, and lived in different parts of South Africa. She now lives in the Overberg on the bank of the Kleine River in the Cape, a spot not too different from the home of the protagonist, Caz Colijn, of SACRIFICED, which was released last year in South Africa and the U.S. to critical acclaim. The New York Journal of Books said: “SACRIFICED places Chanette Paul among the classiest thriller writers of our day.” High praise indeed for her first novel in English!

SACRIFICED has a broad scope—starting in the Belgian Congo in the 1960s, it has ripples of murder and of rape of the rich resources of that country, spreading to South Africa and to Belgium itself. Caz lives a quiet, solitary life, having been rejected by her moralistic husband and family. Unexpectedly, she receives a call from Belgium to say that the woman she thought was her mother is dying, and wants to tell her the true story of her birth. Reluctantly, she goes to Belgium, where her family now lives, and learns that the people she thought were her parents were paid to bring her up by her real mother, who abandoned her at birth. But while Caz searches for the truth about her past, others are interested in her mother because of what she took with her from the Congo. The fact that Caz responds to the call starts a chain of intrigue which threatens all in her strange extended family.

What attracted you to writing novels, and when did you start writing seriously?

Stories have fascinated me ever since I can remember. I started writing stories when I was about eight. My first success was when I was 16, a fairy tale which was read on a children’s program on the radio. The second, in my final school year, was a short story about teenage love, published in a family magazine. My next story was rejected, and so were a few after that. I came to the conclusion that I had it wrong. I was, after all, not meant to be a writer.

It took me 20 years of doubting my abilities before I decided it was now make or break. In 1995, I took the proverbial bull by the horns. I wanted to write the sort of books I enjoy reading, stories that play out from A – Z, full of things happening to interesting people. So, novels were a natural choice. To test the waters I started off with a romance novel—probably to counter the rough seas of matrimony I had experienced at that time. It was published the next year and after that I couldn’t stop. I’ve experimented with many genres since then, but suspense novels and thrillers have been my drug of choice from 2007 onwards.

You have a big following in South Africa—over 40 published books—and have won a number of prizes, yet this is the first one of your books available in English. Was this book designed to appeal to a broader audience?

I was approached by a Belgian agent whose wife can read Afrikaans and loved my books. He asked me if I would consider writing a novel set in Belgium for possible publication in Dutch.

I agreed on the condition that my main characters would be South African as I thought it would be presumptuous to try to write from a Belgian point of view. Also, I had to take my South African readers into consideration as I write for them in the first place.

So, the novel and the sequel were intended to appeal to an audience in the Low Countries as well as South African readers. It was well received and my publishers thought it might appeal to an audience in English speaking countries too. I dearly hope they were right!

Much of the book takes place in Belgium and it’s clear that you know the country. Did you live there in preparation for writing SACRIFICED, or was living there what gave you the idea for the theme?

This whole project was a huge challenge as previously I’d only been in Belgium for two days and that more than 20 years before. I realized I had to go there if I wanted the book to be authentic. So I took the prize money from an award I had just won, dug into my mortgage account, begged and borrowed elsewhere, and set off to Belgium for a month. By that time, I was petrified. I had no story, I’d never travelled alone overseas and I’m a nervous traveler even when accompanied.

I didn’t go there to find my story, but to absorb the country and its people so I can portray both to the best of my ability. All I knew more or less for sure was that it would be logical for the Belgian Congo to be the nodal point between South Africa and Belgium in my story.

I walked miles, sat at street cafes, drank local beers (and to my delight discovered kriekbier), ate Belgian food, and eavesdropped on as many conversations as possible. It helped a lot that my mom was Dutch. I can’t speak Dutch or Flemish, but I understand it well and read it quite fluently.

I had many lucky breaks. I had the privilege, for instance, to go to lunch with a history professor who had headed the commission of enquiry into Patrice Lumumba’s death, and he imparted not only a fountain of knowledge about the murder, but also about life in the Belgian Congo, how the country gained independence as well as the aftermath.

I also had the opportunity to visit the largest diamond bourse in Antwerp, where the then president of the bourse showed me a whole bag full of raw diamonds, let me touch and—I must admit—fondle them. Amongst other valuable information gained from him, he also explained the pipeline diamonds follow after they’ve been mined.

While there, I discovered so many things in Belgium that peaked my interest, that I couldn’t decide what to take and what to leave. It was only when I got back to South Africa that the story slowly started to crystalize. After Caz materialized, it became an organic process. I found my story as I wrote.

Caz is a powerful character. She has strong motivation and has been forced to be self-sufficient, yet she’s out of her depth alone in Belgium seeking the answers to her past. There’s a feeling of isolation about her not only in Belgium but in South Africa also. Was this the aspect of character you were trying to explore here?

Yes. Caz’s whole background—what was known to her and what was not—molded her into a strong woman. Yet, under the armor she had to establish to survive, she is also vulnerable.

The ways in which she was atypical led to her feelings of isolation. Firstly, she grew up in a dysfunctional family that as immigrants had been seen as different by the rest of the community. Then she married into a family with stature and convictions very different from her own. South Africa’s past as well as the current situation here, helped form a barricade she had to put up between her and the rest to create a comfort zone for herself and her daughter.

Erevu Matari is another strong character. Totally ruthless and clearly deluded, yet you manage to show him as an almost inevitable product of the apocalyptic past events in the Congo. He’s so scary because he’s so believable. Where did he come from?

I’m never sure where my characters come from. And even when they appear, it takes me almost to the end of the book to get to understand them. So I don’t invent characters, and certainly not for a certain purpose. While writing I try and find out who they are and what they are trying to tell me.

Through Caz I came to explore how one can still deeply love a country that has turned its back on you. How you can still love a country that has changed into something you hardly recognize. A country that has become so dangerous you have to live behind bars.

Erevu brought to the table how it feels when your roots have been vandalized by people who had no right to do so. Through Erevu I came to explore what happens when one feels a country has been stolen from you. How you see descendants and accomplices of the thieves that did the stealing and mistreated the inhabitants. What the effect and consequences of a violent history could be on a man like him.

In both cases I explore one’s inexplicable emotional entanglement with your place of birth. And how the place where you were born and grew up is part of your DNA and collective memory.

In contrast, Professor Luc DeReu seems unable to move his life from its boring rut, yet as he’s sucked into Caz’s search, he slowly finds he can go beyond the narrow confines he has set himself. How did you envisage his role in the story?

Only in hindsight do I realize that he was something of a rectifier. Whereas Caz and Erevu come from the tumultuous, often cruel and bloody continent of Africa, Luc grew up in a stable country. Yes, there had been a horrendous war, but it was before his time. Cities and relations between countries have been rebuilt, order restored. Yes, the Belgians had to deal with the atrocious crimes of people like Marc Dutroux, but those are exceptions. On average they live very civilized lives in comparison to people in developing countries. In a country like Belgium you need to be efficient rather than brave.

Luc never personally experienced political and cultural tumult; he just studies it. I think he finds it exciting to try to figure out how violence and colonization shaped Africa and is still shaping it today. But he does so academically and as an outsider while Caz and Erevu experience it close to the bone.

The book also explores racism through the eyes of your characters. It’s not the institutionalized racism of apartheid South Africa, but rather the ingrained racism of individuals. Did you set out to do this, or was it almost inevitable given the nature of the book?

It was inevitable that racialism became part of the story. I’m not a political animal and it’s the first time I’ve ventured into this shaky area in one of my novels. It’s such a touchy, sensitive issue, I would have liked to bypass it, but there was no way I could.

One thing I knew from the start was that Caz couldn’t be your typical white liberal. Through her I explored what an average South African woman, born from immigrant parents and brought up in the apartheid-era would experience when she gives birth to a baby that defies explanation.

I hope her story gives a balanced view of racialism as a universal problem rather than just inherent to South Africa and also as not merely a white on black issue. In the sequel, I had to delve even deeper into concepts like re-Afrikanization (yes, with a “k”) and dewhitenization.

As I find it a bit conceited to use a story as a vehicle for a certain message, it wasn’t my intention to advocate one, but I do hope Caz’s story gives the reader something to think about in this divided world we live in.

Although SACRIFICED works well as a stand-alone, there are plenty of themes to carry forward. I know there’s already a sequel in Afrikaans. Do you plan to bring that out in the U.S. also? And could you tell us a little about it?

Yes, there is a sequel. It’s been translated into Dutch but not yet into English. My publishers will have to see how SACRIFICED fares before making the decision as translation is a very costly business—especially brick-thick books like mine.

In the sequel the loose threads at the end of SACRIFICED get explored and tied, and new issues arise. Caz remains the main character, but the story revolves to a large extent around Lilah and her lover, Aubrey. The Congolese thread is broadened and where Caz tries to find out who her mother is in SACRIFICED, she and Luc DeReu try to identify her biological father in the sequel.

Both books work with the concept of sacrifice but from different angles. In SACRIFICED, Caz (and others) are sacrificed by people who follow their own agendas regardless of the harm caused. In the sequel, Caz is prepared to put everything on the altar to save her daughter, even her life.

Find out more about Chanette and her work on Facebook.

- Out of Africa: Annamaria Alfieri by Michael Sears - November 19, 2024

- Africa Scene: Abi Daré by Michael Sears - October 4, 2024

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024