International Thrills: James Oswald

Finding a Peculiar Obstinacy

“I’ve never been good at planning,” admits Scottish author James Oswald. “My approach to writing is more throw everything at the wall and see what sticks.” The same might be said of his path to publication, which I’d read about six months before first meeting the author at Iceland Noir in 2013. The story is well documented, but in case you missed it…

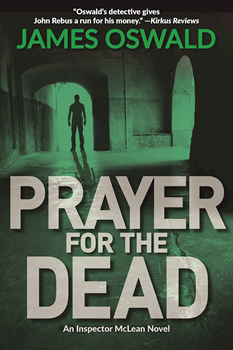

Oswald’s novel Natural Causes was short-listed for the Crime Writers’ Association Debut Dagger in 2007. Undeterred when the book garnered no interest from agents or publishers, the following year he submitted The Book of Souls. Again, the short-list. Again, no interest. There was no market for books blending crime fiction with the supernatural, he was told—an attitude which changed when he self-published the two books in 2012 and 350,000 copies were downloaded in six months. He signed with an agent and Penguin won a bidding war, offering him a hefty advance. They published his sixth Inspector McLean thriller last year and US publisher Crooked Lane Books will release number five, PRAYER FOR THE DEAD, in February.

Oswald also runs a 350-acre livestock farm that overlooks the River Tay in the Highlands of Scotland. We met again at Iceland Noir in November and he generously agreed to answer a few questions for The Big Thrill.

Which came first: the farmer or the writer?

I was a writer long before I became a farmer, but farming was always in the background. My father was raised on, and was meant to take over, the family farm in Easter Ross, near Tain, but it had to be sold before he was old enough. He ended up, as you do, going to London and working as a stockbroker and financial analyst for 25 years and always hankering after the farmer’s life. I grew up in north Essex, and my first jobs were helping out on local farms—most memorably plucking turkeys at Christmas.

In the mid ’80s, my father made enough money to fulfill his dream and bought the farm where I now live in Fife. I went to Aberdeen University around the same time, and helped out with harvest, lambing and calving whenever I could. I was always writing stories though, particularly comics. When I graduated, I worked a bewildering number of different non-career jobs simply to feed my writing addiction. Farming was in the blood though, and I ended up on a research farm in Wales, as an agricultural consultant specializing in farm IT, of all things.

My parents died in a car accident in 2008, prompting my swift return to Fife, to take over the farm and put into practice all the things I’d been telling Welsh farmers to do for years. I now understand the wry looks they used to give me. Even as I was adapting the farm to my own preferred system of farming, I had my mind on being able to write. My choice of Highland cattle and New Zealand Romney sheep was based largely on their hardiness and ability to live outdoors all year round. They might not be as profitable as intensively reared breeds, but they leave me with time to write.

Why crime novels? Were you a fan of mysteries as a young reader?

Far from it. I grew up reading comics. I also loved fantasy and SF, but read very little crime fiction. I went through an Agatha Christie phase in my early teens, and read a lot of Dorothy L Sayers because she had been a friend of my grandfather, so there were plenty of her books lying around. (Little known fact: my mother’s first cat was given to her by Dorothy L Sayers, and was called Harriet after Harriet Vane.)

It wasn’t until Stuart MacBride—who I’d made friends with in Aberdeen, bonding over a love of comics, beer and good food—had his big publishing break with the first Logan McRae book, Cold Granite, that I tried to write a crime story on his suggestion. Before that I’d been writing unpublishable SF, epic fantasy based on Welsh sheep breeds and strange urban fantasy fiction.

With the old “write what you know” axiom, it might’ve seemed natural to place your stories in a rural setting. But you chose Edinburgh.

Having lived in the countryside most of my life, I remain unconvinced about rural crime fiction. There are plenty of great rural crime series, but the city offers so many more possibilities. In the countryside everyone knows everyone else (or at least thinks they do), so the reaction to crime is either a community falling apart or coming unexpectedly together. Communities within cities are often more social constructs than geographical ones, and you can live for years in an apartment block without exchanging more than a cursory nod with your nearest neighbor. The city is a place full of lonely people, ripe for a terrible tale.

One of my earliest comic scripts was a ghost story set in Edinburgh. One of the supporting characters was a policeman who was somehow able to see, just out of the corner of his eye, the lost spirit that was wandering the streets upsetting all manner of things. In that story he was called John McLean, but someone pointed out that Bruce Willis’s character in the Die Hard movies is John McClane. So I changed him to Tony. When Stuart suggested I try crime fiction, the first thing that came to mind was Tony McLean. Edinburgh lends itself wonderfully to the slightly sinister and otherworldly tones of my stories. There is so much bloody history, so many macabre and brutal characters, and so many layers to the place it just begs to be written about.

As an aside, I’d add that like much of the advice given to aspiring writers, “write what you know” is bunkum. Let your imagination run free.

Tony McLean is a more likeable hero than many others in current crime fiction. A deliberate choice in creating the main character for a series?

I was aware enough of the tropes to want to avoid them as much as possible, so while he likes a drink he’s not dependent on it. Like most fictional detectives though, he is driven to the work he does by a combination of tragedy in his past (the murder of his fiancé) and by a single, powerful character trait—in his case that wonderful Scottish word thrawn. Thrawn is a peculiar obstinacy, an insistence on doing something simply because others either think you shouldn’t or don’t think you can. Tony has a burning desire to see justice done and to protect the innocent, but he also won’t give up because that’s what all his colleagues want him to. I would add that I never really set about designing a character with writing a series in mind–I hardly set about designing a character at all. Tony McLean came about by a series of happy accidents over the course of some 20 years.

As to the reason publishers initially gave for rejecting your books. What inspired you to include the supernatural? Did you have any inkling you might be adding something new or provocative to the crime fiction genre?

As a student of psychology I’m fascinated by the depths of depravity people can plumb and the incredibly creative ways they can justify themselves. I like to tease the possibility of demonic influence as the reason for people doing the horrible things they do, when at the end of the day it’s always a person’s choice whether to bow to that influence or ignore it.

As someone who hadn’t read a great deal of crime fiction, I was keen not to copy too much of which I had. Adding in a supernatural element to the tales seemed to me a good way of avoiding that, and from my comics perspective it didn’t seem all that provocative or new. I was surprised at just how hostile the UK publishing industry was to the idea. Oddly enough, I think the US is much more receptive despite (or perhaps because of) it being a far more fundamentally Christian society than the UK.

The popularity of supernatural thrillers seems to be growing. If the protagonist’s intuition is often a factor in solving a case, dealing with the supernatural shouldn’t be such a leap, should it?

I don’t think so, and of course early crime novels often had elements of the supernatural in them. Conan Doyle was a firm believer in the supernatural, even if Sherlock Holmes was the ultimate logician. The rise in popularity of supernatural thrillers is perhaps a reflection of the times in which we live. One of the wonders of the internet is that it brings the entire world into your living room, but for many that is a curse rather than a blessing as old certainties are stripped away. It’s not quite as simple as the G. K. Chesterton quote, “When people stop believing in God, they don’t believe in nothing, they believe in everything.” Many people cling to their faith in the face of information overload but they also seek solace in the simple explanations, even if they don’t really believe them. So reading stories where the evil of the world is down to the devil, or demons and ghosts interfering with otherwise normal people, brings a certain degree of comfort.

There’s much discussion at festivals such as Iceland Noir or Bloody Scotland about Tartan Noir, a term actually coined by James Ellroy to describe the work of Ian Rankin. What elements connect Scottish crime writers? Do you consider your own books part of Tartan Noir?

I’m always wary of titles like these. Technically very few authors I know write proper “noir” for one thing and “Tartan” to me means Edinburgh Rock, Shortbread Tins, and Scottish Country Dancing. There has certainly been an explosion of Scottish writing, particularly in the loosely defined area of crime fiction, in the past 20 years or so. Inasmuch as some of that writing portrays a dark and gritty side to Scottish life and society, you could call that noir, and I suppose my books fall under that label. My father’s family is Scottish, but I was born in the south of England. As such, I wasn’t raised as much in the Scots tradition of storytelling. Sometimes I feel a bit of a fraud penning stories set in Edinburgh and tapping into a Scots history and mythology I am only half connected to. On the other hand, most authors feel they are frauds and live in fear of being found out.

One last question. Early in Natural Causes Tony McLean claims that he’s not afraid of the dark. What scares you?

As a child I was terrified of the dark and the monsters lurking everywhere. I have a vivid memory of sneaking downstairs to watch television—in the house where I grew up we could peer through a crack in the door at the bottom of the stairs and watch whatever my parents were watching without being seen. It was a film version of War of the Worlds, and the alien tripods fired a death ray at people, leaving only the smoking outlines of their skeletons on the ground. Aged around six, this freaked me out so much I barely slept for weeks. I was a precocious reader and probably read far too many horror novels as a child. Mostly I just had a very vivid imagination that always seemed to come up with the worst possible thing that could happen in any given situation. I’ve no idea where it comes from, but it’s stood me in good stead as an author.

To learn more about James Oswald, visit his website.

- International Thrills: Johana Gustawsson - October 31, 2017

- International Thrills: Britta Bolt - July 31, 2017

- International Thrills: Anne Holt - May 31, 2017