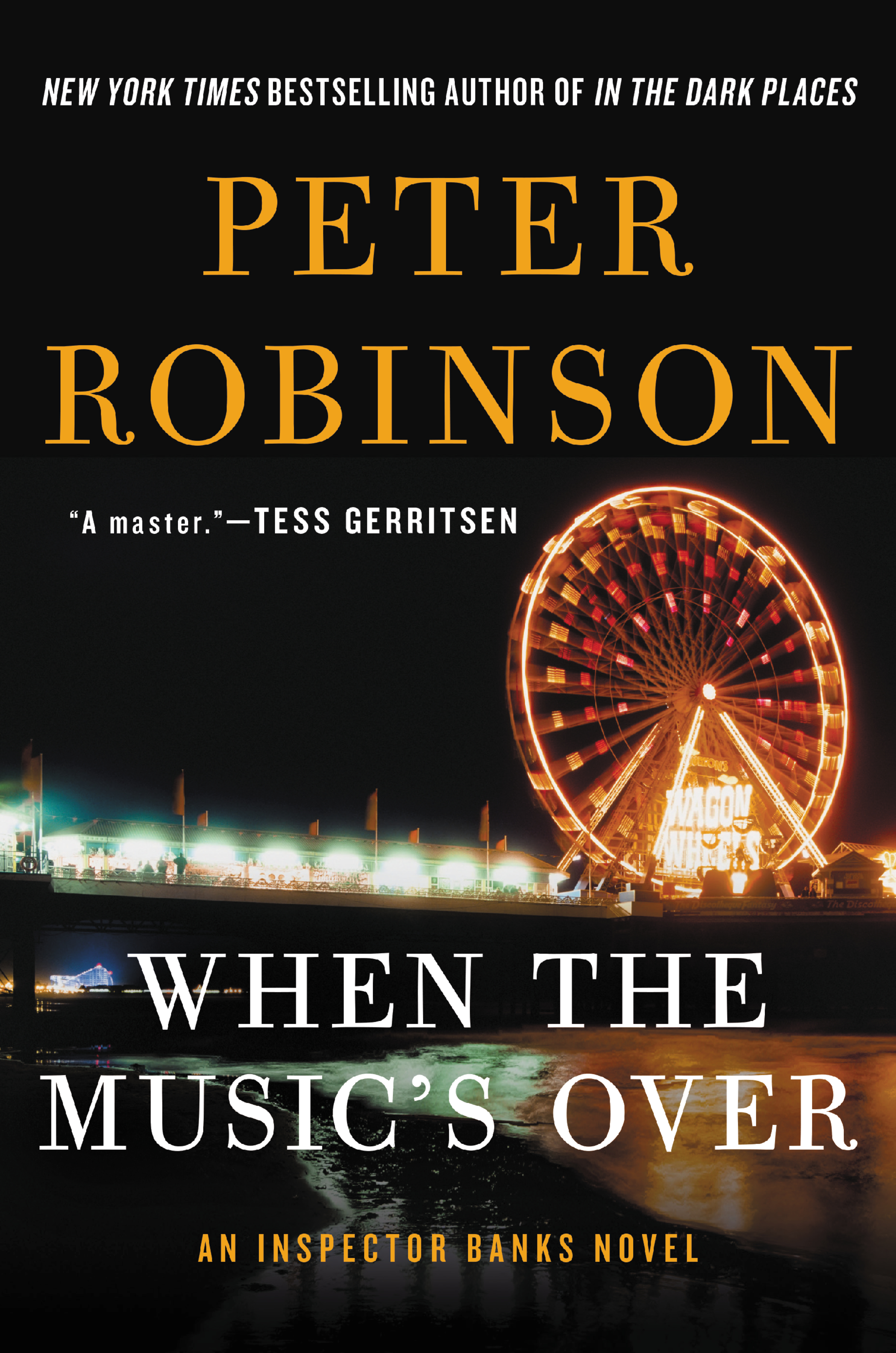

When the Music’s Over by Peter Robinson

Crime Fiction Ripped From the Headlines

In 1987, Inspector Allan Banks made his first appearance in the crime novel Gallows View. Canadian author Peter Robinson won glowing reviews for his novel, which followed Banks’ move from London to the Yorkshire town of Eastvale. This summer marks the 23rd outing for the tenacious Banks, in the novel WHEN THE MUSIC’S OVER. In between the two publications, Robinson’s series has earned a loyal following, consistently good reviews, and awards ranging from the Anthony and the Barry to the Edgar and CWA’s Dagger in the Library.

WHEN THE MUSIC’S OVER is set in Eastvale, as were its predecessors. Robinson, who was born in Leeds, draws on his childhood memories of Yorkshire, in part, to create the fictional town. Robinson has said: “Eastvale is modelled on North Yorkshire towns such as Ripon and Richmond, with cobbled market squares, rather than the kind with one main high street, like Northallerton or Thirsk. I had to make it much larger than those towns, of course, otherwise who would believe there could be that many murders? I’ve probably killed the population of the Yorkshire Dales three times over as it is!”

His new novel is a taut and well constructed mystery that, while following a murder investigation, also fearlessly plunges into controversies raging in England in recent years. Robinson, a Toronto resident who teaches writing, discusses his work with The Big Thrill.

In WHEN THE MUSIC’S OVER, you write about not one but two highly polarizing subjects: the connection between young, poor English women and immigrant sex trafficking, and the past sexual crimes of a celebrity. What motivated you to incorporate both? Do you see a thematic connection?

Yes. I first thought it might be two different novels and then I realized that the stories shared a theme. In both cases, underage girls are exploited and abused by men, and those individuals and institutions supposed to help them—also mostly men—fail to do so for a variety of reasons, different in each case. Running the two stories together also allowed me to compare and contrast sexual attitudes of the late 1960s with those of today.

How important is it to bring social inequality and injustices and pressures into crime fiction, and not just write a murder-mystery procedural?

It depends on the writer. For many, the straightforward murder-mystery procedural is enough. I’ve written some books like that, myself, and I’m proud of them. But one of the things that drew me to crime fiction in the first place—through Chandler, Ross Macdonald, Simenon and Sjöwall and Wahloo—was that it is also an excellent way to highlight society’s failings and injustices.

How has Inspector Banks evolved over the series?

In far too many ways to mention. It still amazes me that this is the 23rd Banks novel. He started out in his mid thirties, having just moved with his family from London to the Yorkshire countryside, and now he is well settled there, but over sixty, and alone. He has certainly become more isolated over the years, and perhaps more melancholy and philosophical as a character. But he hasn’t lost his essential humanity and compassion, or that twinkle in his eye.

The novel is plotted very carefully with clues and some misdirection. How do you plan your books before you begin writing?

I don’t. I just pitch in there and start writing. When you think about it, one scene logically leads to another—through questions that need to be asked, problems that need to be solved—and I follow the trail. It would be boring for me if I knew my destination before I got there. Naturally, I get lost on the way from time to time and have to go back to retrace my route, but that’s all part of the process. With two stories like this, I also separated the strands when I had finished the first major draft and went through each story line separately before I interlocked them again.

Inspector Banks’ personal feelings for a woman who comes forward play a significant role in the book. Is that tricky to write?

It wasn’t tricky for me. Banks is fascinated by people and what makes them tick. That’s one reason he is so good at his job. Though he might never admit it, he is also very strong on instinct, too, the hunch or gut reaction. Linda Palmer, the woman you are referring to, is a famous poet who has survived and recovered from a traumatic experience, and it’s only natural that this should engage Banks’s curiosity. He also comes to admire her intellect, her honesty and her strength as the relationship progresses.

What advice do you have for writers beginning crime series?

Don’t. We don’t need the competition! No, seriously, I’m not sure you should treat it that differently from writing any novel, except you don’t have to reinvent the wheel every time. Don’t get complacent and fall into a formula, though. Vary the structures of your novels, take a few risks, and don’t be afraid of your protagonist turning out to be an ordinary man or woman. You don’t need gimmicks to make a character work.

What is your next planned novel?

It’s another Banks novel, at the moment called Sleeping in the Ground. I’m about halfway through it right now and just had to take a bit of a break for a tour to promote WHEN THE MUSIC’S OVER, but I hope to get back to it soon. At some point in the future, I’d like to do another standalone, like Before the Poison. I really enjoyed writing that.

*****

One of the world’s most popular and acclaimed writers, Peter Robinson grew up in the United Kingdom, and now divides his time between Toronto and England. His books, including the Banks series, three standalone novels, and two short-story collections, have sold more than ten million copies around the world. Among his many honors and prizes are the Edgar Award, the CWA (UK) Dagger in the Library Award, and Sweden’s Martin Beck Award. The Banks novels have been adapted for the ITV series DCI Banks, currently in its fourth season and airing on PBS in the US.

One of the world’s most popular and acclaimed writers, Peter Robinson grew up in the United Kingdom, and now divides his time between Toronto and England. His books, including the Banks series, three standalone novels, and two short-story collections, have sold more than ten million copies around the world. Among his many honors and prizes are the Edgar Award, the CWA (UK) Dagger in the Library Award, and Sweden’s Martin Beck Award. The Banks novels have been adapted for the ITV series DCI Banks, currently in its fourth season and airing on PBS in the US.

To learn more about Peter, please visit his website.

- Up Close: Kris Waldherr - September 30, 2022

- Up Close: Wendy Webb by Nancy Bilyeau - October 31, 2018

- Between the Lines: J. D. Barker - September 30, 2018