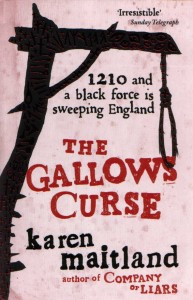

The Gallows Curse by Karen Maitland

by Tracy March

by Tracy March

Karen Maitland’s latest medieval thriller, The Gallows Curse, highlights a perilous time of political and religious turmoil rife with mischief and murder. The U.K.’s Metro calls The Gallows Curse “a wildly atmospheric and wonderfully gruesome adventure.”

The year is 1210. A vengeful King John has seized control of the Church, leaving corpses unburied and the people terrified of dying in sin. In Gastmere, Norfolk, the death of the Lord of the Manor devastates the village when his loyal friend devises an unusual means of cleansing sin from the soul of his master. He uses a young servant girl who becomes the unknowing focus for decades of hatred. She makes a decision that puts her life in danger, and all the lives of those around her.

Recently, I chatted with Karen about The Gallows Curse and its quirky cast of characters.

You are fascinated by the myth, magic and life of the Middle Ages—so much so that for eighteen months, you lived the medieval lifestyle for real, in a rural village in Nigeria. How did the reality of the experience compare with your research and imaginings?

No amount of research can prepare you for the feeling of helplessness at not being able to control the basic elements of your life. Crops which were healthy one day could be dead the next and if they failed there was absolutely no safety net. If everyone’s crops died in that area, there was nowhere even to buy food, assuming one had money.

If your house caught fire or someone tried to kill you, the only people who could help were your neighbours. So community relationships were vital. If, for any reason, someone was outcast from that community, it could literally be a sentence of death. The fear and horror of being shunned by a community on which you utterly depend for survival is something we can’t really imagine in modern cities.

In Nigeria, I found myself living next to the village brothel. Since the only water source for my little house was in their courtyard, I got to know the women and their children well. Although medieval brothels were renowned for their inventive ‘toys’ and their bathhouses or stews, those weren’t a feature of the Nigerian brothel. Yet other features were the same and I was able to draw on many details, from what the women told me, for scenes in The Gallows Curse.

You refer to life in the Middle Ages as a constant battle between light and darkness. How does this play out in the themes of your novels?

One of questions which occurs regularly in my novels, especially in The Gallows Curse, is – in the battle between darkness and light, can we always tell which is good and which is evil? A flame can light your way or cook your food, but flames can kill and destroy. Darkness can hide you when you are in danger, but darkness can also conceal those who want to harm you.

One of questions which occurs regularly in my novels, especially in The Gallows Curse, is – in the battle between darkness and light, can we always tell which is good and which is evil? A flame can light your way or cook your food, but flames can kill and destroy. Darkness can hide you when you are in danger, but darkness can also conceal those who want to harm you.

I think this was the dilemma faced by people in the Middle Ages who were trapped between the promise of heaven and threat of hell, between the power of demons and of angels. The Church, which offered hope, was also the instrument of punishment and fear, forcing people back into ancient rituals which, though dark, were actually comforting because they offered a feeling of control in their lives.

In The Gallows Curse, it isn’t always obvious whose side anyone is on, or which is the ‘good’ side? The French, who are planning to invade England, believe that their army will liberate the people of England and overthrow a despotic tyrant, but the English are terrified of a foreign army coming to conquer them.

The mandrake who narrates the story has the power to give people whatever they ask for, but is this an act of kindness or malice? And it is one of the central characters, the eunuch, Raffe, who typifies the battle. There is darkness and light in equal measure in his soul, the question is, which one is he acting from?

The Gallows Curse is set in the year 1210, during the reign of a vengeful King John, when England was under sentence of excommunication. What chaos did this create, and how does the chaos affect your characters?

The post of Archbishop of Canterbury was the most powerful ecclesiastical position in the realm, so King John naturally wanted an archbishop he could control. But, for exactly the same reason, the Pope appointed his own favoured candidate.

When John refused to accept this, the Pope ordered that England be placed under an interdict which meant that the churches were closed to the laity and people who died couldn’t be buried on consecrated ground. This was a frightening prospect because corpses laid in unconsecrated ground were prey to evil spirits and demons.

Even under the terms of the interdict, absolving the dying was permitted, but John retaliated, seizing the Church’s property and arresting the clergy. The priests fled into exile, so in many places no priests could be found to hear the confession of the dying. In the Middle Ages, they believed if you died in sin, you went straight to an afterlife of eternal torment, a terrifying prospect both for the dying and their families.

Up to then, people accused of a crime could swear an oath of innocence before a priest under trial by ordeal, but with no priests left to administer the oath, the local lord could simply order punishment or execution without a trial.

In The Gallows Curse, a knight dies with a terrible sin on his conscience. No priest can be found to shrive him. Raffe, his loyal friend, swears on the knight’s deathbed that he won’t allow this sin to drag the knight to hell. In desperation, Raffe resorts to a horrible and ancient method of cleansing his friend’s soul, using an innocent servant girl, with terrible repercussions for her and all those around her. To make matters worse, a new lord of the manor arrives with every intention of imposing his own brand of justice, and now there isn’t even a priest to restrain him.

Speaking of characters, The Gallows Curse features a very feisty dwarf and a eunuch with a hunger for revenge. From where did you draw inspiration for these characters?

I love writing about people who are on the margins of society and who, simply by existing, are a challenge to the values of that society.

People with dwarfism were treated as freaks of nature. If they were lucky, they might be taken into wealthy homes to entertain. If not, they could be sold as slaves abroad. The female dwarf in the novel had been cruelly used as a child, but she was determined to take control of her situation. She believes in survival, but she’d done far more than simply become a survivor, she’d become a victor.

I modelled her on a woman I once met on an inner-city housing estate when I was conducting interviews for a non-fiction book. She was a tall, well-built lady but she’d suffered such an abusive childhood that it would have made most people shrink into submission and destroyed their lives. But she refused to think of herself even as a ‘survivor.’ She called herself a ‘fighter’ and woe betide any government official or knife-wielding gang member who thought they could intimidate her. Her determination was the model for my feisty dwarf, though I hasten to add they were not in the same profession.

Castration was highly stigmatized in medieval society, even though it was often used as a ‘cure’ for hernias. Conquering armies frequently castrated their prisoners as a means of humiliating them. Castration was also a punishment for ‘sexual deviancy’ or adultery with a married noblewoman. The villagers in the novel mock Raffe for being castrated and speculate on how he came to ‘mislay his testicles.’ I won’t spoil the story by telling why he was castrated, but in a society where the fathering of children was considered one of the most important things a man could do, Raffe’s castration has a profound effect on his personality and life.

Also in The Gallows Curse, a young servant girl becomes the unknowing focus for decades of hatred. She makes a decision that puts not only her own life in danger, but all of the lives around her. What compelled you to choose a young servant girl as the catalyst in your story?

Elena, as a girl and a serf, is at the very bottom of the medieval heap. She has no real redress in law over those who have the power of life or death over her. I loved the idea of making a girl who is considered so insignificant that the nobles didn’t even bother to learn her name, into the catalyst who unwittingly blows their lives apart through her actions.

Elena was born a serf, because her parents were serfs. Serfs were bound to the manor where they were born and were compelled to do many unpaid days of work a year for the owner of the manor lands. Serfs couldn’t marry without the consent of the lord of the manor and, above all, they couldn’t leave the village without the lord’s permission.

A serf who ran away could be hunted down and brought back in chains to be severely punished, which adds to Elena’s terror when she is forced to flee the manor. The only way a serf had of becoming a free woman was if she could flee to a town and survive a year and a day without being discovered. Elena is an innocent who has never travelled beyond the manor bounds, so she has no idea the dangers she is walking into.

You also jointly write medieval thrillers with a group of historical crime writers known as the Medieval Murderers—Susanna Gregory, Philip Gooden, Bernard Knight, Michael Jecks and Ian Morson. How does your creative process differ when you write?

When I’m writing my own novels I start by taking a idea, usually a modern issue such as ‘people smuggling,’ and look for a time in the Middle Ages when that was a problem too. Then I create two or three strong characters with major problems and the plot evolves from the decisions they take (usually the wrong ones) to resolve them.

This process is almost the reverse of the way I write with the Medieval Murderers. Before we start a joint thriller, we all agree on an object or place to link our novellas. In The Sacred Stone, it was a small meteorite that fell to earth in Viking times. In Hill of Bones, we decided that each of our novellas would somehow culminate on Solsbury Hill, an ancient iron-age fort near Bath in England.

We then have the challenge of weaving the object or place into a murder-mystery set in our individual time periods. We also must include elements from the Prologue which one of us creates. The author who has the most difficult job is the one who also has to write the modern Epilogue, tying strands from all five medieval novellas together and bringing it to a new climax.

Tackling the joint thriller forces me to think backwards from the object or place. Why would someone in my period, 1241, be desperate to acquire a meteorite? What powers might they believe it possessed? Or why would someone in 1453 go to bare hilltop outside Bath and commit a murder there? Who would they murder? Approaching a story like this reminds you that it is possible to create a tale from anything and that there is no such thing as writer’s block.

I think it is good for authors to break out of their usual creative process. If writers find that the water in their creative well is running low, it’s always worth approaching the next story from a new angle, for example, starting with a place instead of your usual method of starting with a character. It’s like sinking a new well shaft; the water will bubble up again in the new hole.

Karen has written two other medieval thrillers. Her first, Company of Liars, was shortlisted for a Macavity Award. Her second, The Owl Killers, was shortlisted for a Shirley Jackson Award and was selected by the American Library Association as one of the best historical novels of 2010.

Visit Karen online at http://www.karenmaitland.com.

- A City of Broken Glass by Rebecca Cantrell - June 30, 2012

- Permanence by Vincent Zandri - May 31, 2012

- If I Should Die by Allison Brennan - November 30, 2011