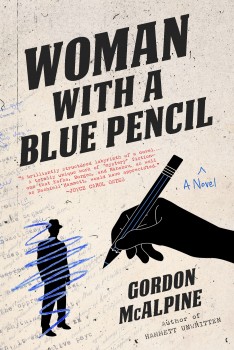

Woman With A Blue Pencil by Gordon McAlpine

By John Clement

By John Clement

Gordon McAlpine’s latest novel, WOMAN WITH A BLUE PENCIL (Seventh Street Books, 2015), is an engaging and imaginative palimpsest of stories, each unfolding in piecemeal through glimpses of letters, notes, manuscripts, and excerpted passages from both historical accounts and novels. The book has been described as a mash-up of Raymond Chandler and Sax Rhomer, as orchestrated by Jorge Luis Borges, and I think that’s not far off the mark. I thoroughly enjoyed it. Earlier this month, I got the chance to talk with McAlpine about the book’s creation.

Your new book is such an impressive feat, with numerous intertwining stories—some fictional, some non-fictional—all unfolding at the same time and yet quite seamlessly. Can you talk about how you came up with the idea for the book’s structure?

The book’s structure consists of three alternating parts; first, the story of an L.A. based Japanese-American detective who’s been “cut” from a novel, yet who persists, unrecognized, on the very streets he thinks of as his home, unaware that he is a discarded fictional character; second, letters from a commercial book editor to a young author that encourage him to make this cut, replacing his work-in-progress Japanese-American protagonist in response to world events (Pearl Harbor), and then turning what had been planned as a mystery novel into a spy thriller; third, excerpts from the “published” spy thriller, featuring the politically expedient replacement character, his anti-Japanese racism sadly consistent with the times, who now squares off against Japanese-American Fifth Columnists infiltrating L.A. The stories wrap around each other like three snakes climbing a trellis. At the risk of straining the metaphor, the trellis, the support for the story, is the young author Takumi Sato, whose compromises eventually create a pulp thriller that answers the demands of his editor, the woman with the blue pencil, and yet ignore the realities of his own life, his family’s persecution and tragic relocation to Manzanar. Sato never appears in the book, yet his experience of writing first one draft for commerce and ambition and then a second version—a repentant and angry return to his original, heretofore unrealized character and the existential problem of displacement—provides the grounding upon which I came to understand the three strands of story as one. It is true that the book is at once a genuine murder mystery played out with dire seriousness, a pulp spy thriller involving a mysterious and almost supernaturally deadly woman, and a character study in seduction, with the woman editor proving a new kind of femme fatale. But for the young author character, who never actually appears in the book, it is also a story about ambition, temptation, loss, and blood redemption.

I was hugely fascinated with the character of Sam Sumida. I might be wrong, but despite the fact that he is the most “fictional” of the characters you’ve created, I feel he is the heart of the novel. Do you agree? Can you talk about his story and the complicated nature of the mystery he finds himself in?

I agree that Sam is the heart of the novel, even if he never fully understands his situation. It is not accidental, I suspect, that you refer to him as the “heart,” since it is Sam whose motivations are the most pure and deeply felt. His wife has been murdered, the police have shown little or no interest in solving the crime, and so he has taken it upon himself to become a private investigator, even though his training is in art history. He is unsuited for the endeavor. But he is determined. What he can’t anticipate is the existential dislocation that occurs at the novel’s opening. Likewise, he can never understand it. After all, who ever could imagine himself a fictional character cut from a work in progress? But Sam’s strength is revealed after he regains a tenuous sense of balance, despite everything, and returns to the matter that consumes him—the solving of his wife’s murder. As Sam says toward the end: “I don’t think the world is ever something you can understand, even when it seems ordinary. So, all you can do is try to figure out what you’ve been put here to do. And then do it.” He does it. But nothing is straightforward for Sam. He knows that his wife, to whom he’s dedicated himself, was unfaithful to him. Additionally, he meets another “version” of his wife who bears none of the gentle or kind qualities he loved. Still, he finds the strength to do what he believes is right, even in a world so full of contradictions. That is a hero, I believe.

One aspect of the story unfolds in the form of letters exchanged between Sam Sumida’s creator, the author Takumi Sato, and his manipulative New York editor, Maxine Wakefield, in the days following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Ms. Wakefield’s primary concern is changing the character of Sumida into something she thinks will be more marketable to American readers, all the while capitalizing on the fear and hatred directed at Japanese Americans at the time. Can you tell us about about your research for the book, and how bigotry plays a part in the story?

I did considerable research about the tragic circumstances of the Japanese-American community in Southern California during those first weeks and months following Pearl Harbor. Aware of the forced relocation and mass internment of law-abiding American citizens, I recognized an historical setting that captured in unequivocal terms the tenuousness with which “outsiders” have always had to live in America and still do. The notion of “revising” a character out of existence due to his race may work here, on one level, as high-wire, literary gamesmanship—however, it is my hope that depicting such a “revision” also addresses and strips bear the dark yearnings of a disheartening segment of our population that seems never to go away. Who is the loathed minority this week? So, yes, WOMAN WITH A BLUE PENCIL indicts the continually shifting sands of bigotry and hatred, a topic as much for our own times as for the historical period of the novel. I hope too that the book addresses the attendant question of how the “editing” of our own identities and our view of others shapes us all.

What was your writing process for this book and how long did it take you to write? Describe your typical writing day.

I wrote WOMAN WITH A BLUE PENCIL in less than eight months, something of a record pace for me, which I suspect had to do with my having lost my father shortly before I began writing it. He was gone, but, for the first time in my writing career, I felt him in the words on my pages (he was not Japanese-American and, excepting his generational ties to the 40’s Swing era, his life bore no outward resemblance to any of the characters). For many years I’d been intrigued by the question of what happens to a character who is cut from a manuscript. So his death introduced nothing new to me there. Likewise, I already had researched the Japanese-American internment and had settled on major plot elements. Still, I felt my father informing the work throughout. Finally, I realized it was the deep affinity I had for Sam Sumida’s dislocation, not merely as a fact but as a feeling . . . it was the authenticity of emotion that I derived, in part, from a similar sense of dislocation that I’d observed in my late father since I was a child. I knew that for all my father’s qualities he feared he might simply be “the wrong kind of man.” For him, that had to do with conventional American notions of success. But feeling you’re the “wrong kind of man”, whether as a self-imposed judgement or as the result of widespread social injustice . . . heartrending. Surely this is one reason I feel so much for Sam Sumida—why he is, as you say, the heart of the novel.

What are you working on now?

The new novel, which will be available in late 2016, is called Two Paths Diverged and is set in London, Cambridge, and Paris in the late 1920’s, engaging a handful of the world’s great and most celebrated minds in questions of deep and dangerous significance. The rest must remain mystery…at least for now.

*****

Gordon MCAlpine is the author of Hammett Unwritten and numerous other novels, as well as a middle-grade trilogy, The Misadventures of Edgar and Allan Poe. Additionally, he is coauthor of the nonfiction book The Way of Baseball, Finding Stillness at 95 MPH. He has taught creative writing and literature at U.C. Irvine, U.C.L.A., and Chapman University. He lives with his wife Julie in southern California.

Gordon MCAlpine is the author of Hammett Unwritten and numerous other novels, as well as a middle-grade trilogy, The Misadventures of Edgar and Allan Poe. Additionally, he is coauthor of the nonfiction book The Way of Baseball, Finding Stillness at 95 MPH. He has taught creative writing and literature at U.C. Irvine, U.C.L.A., and Chapman University. He lives with his wife Julie in southern California.

- Baby Doll by Hollie Overton - June 30, 2016

- Woman With A Blue Pencil by Gordon McAlpine - November 1, 2015

- Blessed Are Those Who Weep by Kristi Belcamino - March 31, 2015