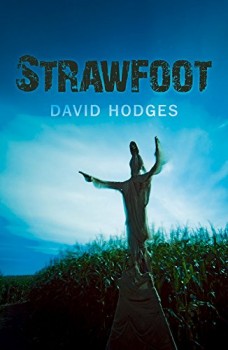

Strawfoot by David Hodges

By David Healey

David Hodges is a British crime writer whose long career in law enforcement informs his fiction with rich details of police procedure.

STRAWFOOT is his newest novel set on the moody Somerset Levels, a coastal area with a penchant for marshes and murders. The case will be the biggest challenge yet for Detective Sergeant Kate Lewis, the main character in the series. In this new release from Hale Books, a murder has the locals wondering if Strawfoot, a sort of bogeyman from local legend, could be behind the killing.

Hodges answered some questions from the perspective of a veteran police officer and crime writer from “across the pond.”

The main character in your thrillers is Detective Sergeant Kate Lewis. Was it challenging to put yourself in the head of a female police officer?

I suppose it was a bit of a challenge making my main character a female detective instead of the usual male stereotype. But I have worked a lot with female officers and have not found them any different in the way they do their job than male officers. I wanted to create a character who was pretty, sexy, but competent at her job, without offering a sop to the feminist brigade by making her a butch-type superhero who can best the men at every stage or fall into the male chauvinist trap of creating a simpering girlie type who needs male protection all the time. Kate is an ordinary “copper” who makes mistakes and achieves successes like everyone else; the only difference being that while she is a brash, forceful and very outspoken character, her partner (now her husband), Hayden, is a more reserved, old-fashioned ex public schoolboy, who often acts as a brake on her activities. (Role reversal of the sexes?)

In your earlier thriller, FIRETRAP, there are several words or terms that American readers could stumble over: copse, “Irish milk,” twitcher, guv’nor, screwed (which turns out to mean “burgled”). As a reader, I thought, “Is this a foreign language or what?” At one point you even stumped the word look-up function on my Kindle. You do have helpful footnotes for police terms, but did you consider adding some kind of glossary for an American audience? I mean, what in the world is a rhyne?

I have the same problem with some American thrillers re colloquial terms and words, so I sympathise with what you are saying. The fact is, my books have had to be written from the English perspective, as that is where the plots take place. At present, though they are read in America, Australia, and New Zealand, the bulk of my sales are in the UK. I would be delighted to increase sales in the USA and a glossary of terms would then certainly be well worth considering, but at present I don’t feel this is justified. Ironically, I did approach my publisher some time ago regarding footnotes on some aspects of police procedure, which would be unfamiliar even to many British readers, but the editor did not feel footnotes or glossaries would be appropriate for a fiction novel. Incidentally, a “rhyne” is a man-made ditch dug to drain flooded fields and is more or less unique to Somerset.

FIRETRAP is set in a rural area, the Somerset Levels, and the opening scene takes place on a farm. Later on there is a chilling scene where Kate nearly drowns when her car is forced off the road through the marshes and farmlands. Yet, Kate has a sister in town who is a heroin addict. Have drugs become a part of even rural areas like the one in FIRETRAP and STRAWFOOT?

Sadly, drugs are as big a problem in some rural areas as in the towns. What has happened is that because the police have applied a lot of heat in the town/city areas, the drug gangs have moved out into the rural areas (what we call the “sticks”) because they can operate more easily in isolated areas where the police are more stretched and less visible. In some rural spots drugs problems have become worse than in the towns. Tragic, but that’s the world we live in today.

Your new thriller STRAWFOOT takes its title from local mythology, about a long-ago killer who terrorized the Somerset Levels. Some fear this monster from the past has returned to kill again. He’s kind of like a predatory Wicker Man. Americans typically don’t have these bogeymen taken from local legend. Is this more of an English thing?

Yes, in England we love our folklore/history and legends about ghosts, witches and mythical black dogs abound. Though the legend of Strawfoot is purely a figment of my imagination, superstitions about scarecrows do exist in many rural areas and I have to say, if you were standing on the marshes of the Somerset Levels in a thick November mist, you would be likely to believe in anything!

How did being a career police officer help you become a writer?

I suppose crime writing was an obvious choice after thirty years in the police. They say writers should write about what they know, so I suppose I have taken the lazy approach and done just that. Having been in “the job,” I feel I can write more persuasively about crime than I could in relation to other genres, like the American West or Military History. When I write about the police, I am there in my mind, still doing “the job,” so I feel I can provide accurate backgrounds to my stories, which, hopefully will carry conviction with my readers.

Tell us a little about your writing process. Do you carefully outline your plot or are you a more organic writer? What kind of writing schedule do you keep?

I suppose my writing process is both organic and structured. I start off with an idea—in STRAWFOOT, it was the sight of dozens of scarecrows one misty night seemingly waving at me from the front gardens of some cottages in the middle of an annual scarecrow festival that triggered the idea. Then I put together a very brief summary of the plot and let the story take me to its own conclusion. I don’t summarise chapter by chapter, though I have a broad notion of where I am heading with a story, and the whole thing develops as I go along. I average about three to five hours solid writing a day, but sometimes more, sometimes less—depending on what my long-suffering and very supportive wife, Elizabeth, will put up with!

A classic red Jaguar Mk2 gets a lot of miles put on it in FIRETRAP and Kate drives a sporty Mazda MX5. You must be a car guy! What do you drive?

I couldn’t be less of a “car guy,” in fact. I drive a Volvo V40 hatchback, which is nice and sporty, but hardly a classic car. I tend to buy cars that are economical, look smart, and don’t incur as much annual road tax (very expensive in the UK) as others. I can appreciate a nice car, but I am far from being an enthusiast and am much more interested in the sort of 1960s motorcycles I used to ride in my teens—though I am too old for any two-wheeled transport faster than a bicycle now! Mind you, if I did have the chance of classic car, it would have to be an Austin Healey 3000.

What’s next for Kate?

My next novel, involving Kate and new husband Hayden, is with my publisher and (ironically, as you have already mentioned the subject), focuses on rural drugs crime—and, of course, murder. Here’s hoping for publication success, but you know what they say—you are only as good as your next book. I have it in mind to have Kate promoted to Detective Inspector in the novel after this one and maybe have a female villain to contend with. But I haven’t made up my mind yet and so far on my travels nothing has triggered that all important idea.

*****

A former superintendent with Thames Valley Police, David Hodges is a prolific writer and former essayist. His crme series, set on the mist-shrouded marshlands of Somerset and featuring fiesty Detective Sergeant Kate Lewis, has gone from strength to strength. David lives with his wife, Elizabeth, on the edge of the Somerset Levels where he can take inspiration from the landscape and fully indulge his love affair with crime writing.

A former superintendent with Thames Valley Police, David Hodges is a prolific writer and former essayist. His crme series, set on the mist-shrouded marshlands of Somerset and featuring fiesty Detective Sergeant Kate Lewis, has gone from strength to strength. David lives with his wife, Elizabeth, on the edge of the Somerset Levels where he can take inspiration from the landscape and fully indulge his love affair with crime writing.

- The Last of Her by Brent Spencer - May 2, 2022

- When Heroes Flew: The Shangri-La Raiders by H.W. “Buzz” Bernard - June 30, 2021

- Eagles Over Britain by Lee Jackson - March 31, 2021