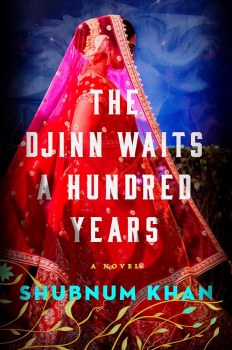

Features International Thrills: Shubnum Khan

Africa Scene: If These Walls Could Talk

The Big Thrill Interviews Shubnum Khan

Shubnum Khan is a South African author and artist who lives in Durban in KwaZulu Natal. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, McSweeney’s, HuffPost, O, the Oprah Magazine, The Sunday Times, Marie Claire, and others. Her first novel, Onion Tears, was shortlisted for several prizes.

Shubnum Khan is a South African author and artist who lives in Durban in KwaZulu Natal. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, McSweeney’s, HuffPost, O, the Oprah Magazine, The Sunday Times, Marie Claire, and others. Her first novel, Onion Tears, was shortlisted for several prizes.

THE DJINN WAITS A HUNDRED YEARS is her debut novel in the U.S. and has already received very strong reviews. In a starred review, Kirkus said: “Khan’s prose is lush and lovely, her pacing skillfull, and she successfully weaves a complex plot…a ghost story, a love story, a mystery—this seductive novel has it all.”

The story is set near Durban at a mansion, Akbar Manzil, that’s fallen on hard times. It’s now owned by a man who’s known just as Doctor, who lets out rooms to a few other people—two ladies who appear to dislike each other intensely, a third who is a pianist and gives lessons, and recently to a widowed man and his 15-year-old daughter, Sana. It’s Sana who discovers the story of the house and the murder that took place there a century before.

Shubnum, would you start by telling us what led you to write THE DJINN WAITS A HUNDRED YEARS?

I wanted to write about Durban, and I’m really interested in love, and mystery, and magic realism. The gothic genre is an amalgamation of many of these elements, so I found the best way I could tell a love story, a ghost story, a mystery, a tragedy in one book was to group them together at a specific location in Durban. It took quite a few years for all these ideas to come together.

I was also interested in the curiosity of a young girl. She’s 15 and doesn’t know what the future holds. She’s carrying all this trauma, but she’s hopeful for the future. I think that many young people are like that—they’re excited about the future but also anxious about it. I wanted to capture that in a novel.

The house is a character in its own right. It’s not haunted in the usual ghost sense, but there’s an invisible djinn—an Islamic spirit—who lives there, pining for a woman who lived there many years before. What is the importance of the djinn’s role in the story?

The djinn is important as a plot device because it bridges the gap between the past and the present. It’s able to tell the reader and Sana what happened, or at least to give clues to what happened in the past. But beyond that, the djinn is really important because it adds to the sense of magic realism in the story. It adds to the sense of surrealism of the house, the unreality of the house, the mysticism of the house. It also adds to the sense of the house being alive because the djinn was the only thing living in the house for so many years after the house was abandoned.

Sana is an introverted teenager trying to make sense of life. She attempts to understand love by reading about it, and by asking people about it and writing down their responses. However, she’s intuitively able to recognize a deep relationship in a visual way, observing that a couple seem to blend together in a photograph, for example. Is this why she becomes fixated on finding out the story of the house and the people who lived there in the past?

Yes, I think seeing the photograph of two people in love does encourage Sana to start exploring the house, and she becomes fixated on the story of the house. Also, she’s so much younger than the other characters in the house, and with youth comes curiosity. She’s at the point of her life where she wonders what the future holds for her, so she’s curious about everything, and she wants to know the story about everything. As soon as she sees the house, she recognizes it has a story waiting to be told, and she wants to know that story. Then, the photograph spurs on her exploration of the house.

I think her curiosity shows that she’s a hopeful person, although she may see herself as depressed. Despite the tragedies of her mother and her sister, she wants to find excitement, to find adventure. She wants to find the light.

In parallel with the present-day story, we learn the story of how the house came to be built. Akbar is an adventurer who falls in love with South Africa and settles there with his wife. Unfortunately, his arranged marriage is a hopeless mismatch. His wife is a traditional Indian Muslim woman who admires everything British and hates Africa. Their marriage is further unbalanced by his mother, who takes over the running of the house and makes all the domestic decisions. Does this triangle reflect the upper-class Indian culture of that period?

Yes, I think it does. The novel explores the interclass interactions between Indians—how Indians with lighter skin thought they were better than Indians with darker skin, that the northerners thought they were superior to the southerners, those who had money, history, or land, regarded themselves as better than those without. Even today, some Indian people aspire to be more like the British. These prejudices were firmly established at that time. I try to exploit this by looking at the relationships around the different marriages between characters.

In the midst of this, the husband falls for and takes as a second wife, Meena, a woman regarded by everyone (including herself) as entirely unsuitable. However, this is the couple that Sana sees in the photograph, truly loving each other. Is it inevitable that this arrangement will end in tragedy?

Certainly, true love doesn’t mean that it will end in tragedy, although sooner or later, it must end in sadness when one loses the other. In a novel, however, it’s clearly a setting in which a tragedy can take place.

Is the crux of the story a murder that takes place in the house—a murder that the djinn is unable to prevent but is perpetually tormented by?

Yes. This is the pivot for the story. The djinn loves the woman and is unable to prevent the murder, so after that, it’s trapped in endless misery.

The tragedy destroys the family who built the house, while a modern tragedy at the house brings the occupants together. Did you see this as a type of balance?

I wasn’t conscious of doing that, but I think sometimes there is a rhythm in your writing which balances darkness in some places with light in others. I think it does provide a balance, but it wasn’t planned that way.

You can follow Shubnum on X (formally Twitter) @ShubnumKhan.

International Thrills: Shubnum Khan

- Out of Africa: Annamaria Alfieri by Michael Sears - November 19, 2024

- Africa Scene: Abi Daré by Michael Sears - October 4, 2024

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024