Features Lev AC Rosen

The Most Welcoming Gay PI in Town

The Big Thrill Interviews Lev AC Rosen

By K.L. Romo

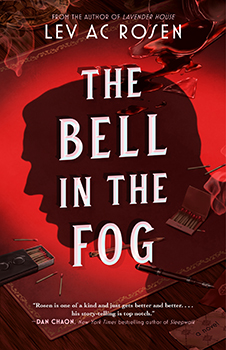

In his newest mystery, THE BELL IN THE FOG, book two in the Evander Mills series, Lev AC Rosen takes readers back to 1952 San Francisco, where being gay—even there—can get you killed.

In his newest mystery, THE BELL IN THE FOG, book two in the Evander Mills series, Lev AC Rosen takes readers back to 1952 San Francisco, where being gay—even there—can get you killed.

The “only queer detective in town,” former San Fran police officer Evander (Andy) Mills keeps his PI office over the Ruby, the most welcoming gay club in San Francisco. With the help of the club’s owner, Elsie, and the Ruby’s popular female impersonator, Lee, Andy tries to prove to the gay community that they have nothing to fear from him anymore. But convincing them is harder than he thought it would be.

“I remember what it’s like to be dragged out and beaten when your colleagues find out the truth…The thing about being a former cop who was fired after being caught in a raid on a gay bar is that all your old buddies on the force would love to win bragging rights for breaking your face.”

An engaging and enlightening detective mystery wrapped around a queer romance, then inserted into a time capsule, Rosen brings the Lavender Scare of the 50s into the spotlight, with its endless justified harassment and “homo-cides” for committing the crime of being gay.

Here, Rosen talks with The Big Thrill about the Lavender Scare, finding family and love in unexpected places, and enlightening readers about our country’s shameful beliefs and actions in queer history.

Why did you decide to write about the queer experience in 1952 versus other time periods in history?

The 50s were a big moment in queer history, but one that is completely forgotten. We all know about the Red Scare, but the Lavender Scare—this huge fear of the government being filled with queer folks—was arguably an even larger event! Many headlines of the time, such as the government filled with moral deviants, etc., are now thought of as being about communists, but they were about queer people. And these headlines were showing up every day. The country was very aware of queer people, and queer people knew very well they were being hunted.

But despite that, queer communities developed and thrived, to an extent. In fact, the reason I chose San Francisco in 1952 is because a lawsuit had made gay bars technically legal in the state. Prior to the lawsuit, serving alcohol in a place where queer people gathered was illegal because a place where queer people gathered would have been considered a “house of ill repute,” like a brothel.

But the straight owner of the gay bar The Black Cat sued over that, and the California supreme court ruled in his favor, saying a bar couldn’t have its liquor license removed for serving queer patrons—though the ruling went on to specify that that didn’t mean queer people could be visibly queer in those spaces. Indecent acts (dancing, kissing, holding hands in some cases) could still get the place closed down.

So, 1952 was a wild time for the San Francisco queer community! They’d advertise drag shows in the same papers that had headlines about “moral deviants” and then get raided by the cops, looking for any excuse to shut them down. It felt like a great period to set some mysteries in.

As you were writing the novel, what went through your mind when comparing what it meant to be queer in 1952 with how things are today?

I’ve been asked this one a lot, and people are always expecting one of two answers, either the “it’s so much better!” which is true in some ways and not true in others, or “so much of what is happening now is like what happened then,” which is also true in some ways, but not others. The real answer, though, is that looking at the past, and how it was to be queer then—terrible, oppressive—and how today we find many people trying to recreate that environment, and succeeding, is sad but also hopeful. Because we’ve gotten through it before.

And even in the 50s, examining what it was to be queer then, we thrived. There were multiple queer rights organizations active in the 50s, and they staged protests, brought together community. Queer bars were all over, and people met in them and fell in love. There was light in the darkness, and yes, that light has shone through as the darkness faded, so things have gotten better, but the darkness is coming back now—but it won’t extinguish our light, because it didn’t before.

That’s a very lofty and pretentious metaphor, but hopefully, the idea comes across: studying the past and how we thrived under terrible conditions makes me hopeful and less afraid of the terrible conditions people are trying to impose on us today.

You noted in your acknowledgments that “even when we’re persecuted, we find family and love.” Can you expand on that? What messages do you hope readers will take away from THE BELL IN THE FOG?

We find our light in the darkness. Today, there are an astounding number of anti-LGBTQ bills being written across the country—rights revoked, people forced back into the closet at work, books banned. But we’ve been here before. We’re used to being a political punching bag for when the right wants to wildly misrepresent us and make us into bogeymen after people’s children. This is Anita Bryant all over again, and it’s a boring remake with terrible acting.

That over half the book challenges in the country come from under a dozen people should tell you how few of them there are and how desperate they are to demonize us and use us to gather outrage votes. But we’ve gotten through it before. I’m not saying it’s been easy or that terrible things haven’t happened to us, but this is what I mean about looking at the past—when you really look at it, you see it wasn’t all one thing. It wasn’t all terrible, it wasn’t all wonderful, and that means the same is true today. Even when it looks terrible, it isn’t ALL terrible. We have to find our communities and our families, like our queer ancestors did. We find hope in community.

That’s what I want people to take away: Hope is always there, waiting for you to join.

What advice can you give other writers, especially about being genuine when writing your characters?

I think for writing characters, the key thing is to see them in all dimensions—they’re not just heroes, not just villains, not just queer, not just surviving. They contain multitudes, and those multitudes are where the realism lies. We’re all filled with contradictions, and we all know it. Even those of us who are passionate, with a black-and-white view of the world, will end up tying ourselves in knots when we encounter that one moment that forces us to make a decision we’ll hate ourselves for.

Know those moments, give those moments to your characters so your reader can see them the way you do. It’s not just about knowing your characters’ humanity inside and out; it’s about finding ways to express that humanity and complexity to your readers.

Will there be a third book in the Evander Mills series?

Yes, there will! Coming October 2024, I believe I can announce that the title is A Bad Story. I’m sure that will expose me to a bunch of pithy lines in bad reviews, but I don’t mind—I wrote a book called Depth, I can handle it. And it’s about books and newspapers, so it makes sense (also the mafia). There were a lot of gay books published in the 50s, many forgotten today. And there were book services that mailed gay books to you, if you signed up… and there was the post office, with its rules about sending indecent materials through the mail. There’s a lot going on, story-wise. Is that a pun? I suspect I’ll be asking that question a lot when I’m doing publicity for that one.

Tell us something about yourself your fans might not already know.

I directed several musicals in college, including the classic noir, City of Angels. I still think the soundtrack is great for getting into a noir mindset.

The Big Thrill Interviews Lev AC Rosen

- The Big Thrill Recommends: ONE BIG HAPPY FAMILY by Jamie Day - September 16, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: ONLY ONE SURVIVES (Video) by Hannah Mary McKinnon - July 30, 2024

- The Big Thrill Recommends: WHAT YOU LEAVE BEHIND by Wanda M. Morris - June 27, 2024