BookTrib Spotlight: Claudia Lux

Think Your Life Is Hell? Think Again.

You already have a lot of ideas about Hell. It’s amazing what Dante and thousands of years of folklore can do to a place’s reputation….On the top floors…it’s not the fire and brimstone thing you think it might be. It’s music that’s too loud, food that’s too rubbery, and kissing with too much tongue. Doesn’t sound that bad, right? But don’t forget, it’s forever. I mean, for-all-time forever…You can’t possibly fathom eternity; your little mortal brain will explode.

The speaker in Claudia Lux’s SIGN HERE is Peyote Trip, a worker bee trying to get his figures up in the Deals Department on the fifth floor of Hell (you don’t want to know what goes on Downstairs), while having to endure endless departmental meetings and obnoxious gloating colleagues. You know the mysterious figure who appears out of nowhere after you’ve said, “I’d sell my soul for…”? That’s him. His favorite technique is the SnowFlake, “flattery and validation…Tell them that they are special, that you’ve been waiting for them. That they have some kind of higher purpose. Humans love that shit.” Then when you’ve got them on the hook, you whip out your electronic tablet and, “All they have to do is click ‘I agree to the above terms’ before they sign. It’s up to them if they read the fine print.”

Peyote has a secret, though. He has a plan for getting out of Hell. It all hinges on a family called the Harrisons. He already has four generations of that family under his belt, and all he needs is one more to put his plan in motion. The perfect opportunity is coming up—the family’s six-week trip to their summer house in the country—and he knows someone is going to crack: the father, Silas, whose brother killed a girl in high school, and then hanged himself in his cell; the mother, Lily, who’s having an affair with the dead girl’s brother; their teenagers Sean and Mickey, each with secrets of their own.

The secrets don’t end there, however. Mickey’s new friend Ruth, along for the trip, has plenty of them. Peyote’s new colleague Calamity, a naïve rookie, turns out to be neither naïve nor a rookie, and has a carefully plotted revenge scheme of her own.

All of these characters, and more, are about to collide in a genre-busting powerhouse of a novel—part thriller, part wrenching family drama, a book that starts out as satire and then veers into something much deeper: an exploration of the nature of love, time, loss, and family ties, of both morality and mortality. Darkly funny, unexpectedly poignant, it might just have you examining your own assumptions about what makes us human—and what might make you “sign here.”

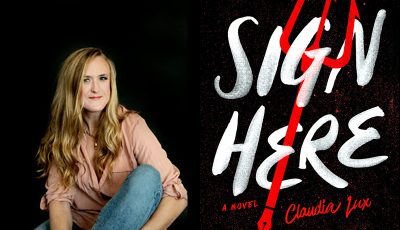

“The first kernel of the idea,” Lux says, “started when I was on a work trip, curled up in my hotel bed after a long day, and realized I couldn’t remember my Hulu password, so I had to watch TV with the ads. THE HORROR. When the same insurance commercial that had played every. other. break. started for the millionth time, I howled, “THIS IS HELL.”

“As soon as I said it, I was hit with the reality of how ridiculous that was: there were so many aspects of that very moment for which I was incredibly lucky. It was far from Hell. But after that, I started noticing it more: how quick we are to compare our momentary discomfort to eternal damnation, how low the colloquial bar has gone for suffering. So I asked friends—or anyone standing near me—what annoyances they had classified as such, and the responses ranged from what celebrities name their children (welcome, Peyote Trip) to multiple pens in a row not working (welcome, Peyote’s pencil case).

“In fact, there were so many annoying, semi-soul-crushing and widely relatable things about the monotony of a 9-5 that I gathered more examples than I could feasibly fit into a book. For those who want to know more about Peyote’s Hell, on my website I have included a portion of the official Hell Orientation Packet.

“So now I had a world to explore, and a character to explore it. For the Harrisons, it started in a similar—albeit ultimately quite different—way: with a location. When I was a kid, I went to my mom’s friend’s home on a lake in New Hampshire every summer, and it was the most magical place, full of opportunities for imagination. So when I needed a home base for a family, I pulled directly from that house, and the characters (nothing like the family I knew growing up, by the way!) formed around it.

“I love writing for so much more than telling a story—and I really love telling stories! I love the way certain words feel in my mouth, I love how they can string together to imitate the increased pounding of a heartbeat or the deep breaths of a languid summer afternoon. I love onomatopoeia (a word my dad used to make me spell before he’d buy me whatever sugary thing I was begging for—very effective) and double entendres and saying just enough to make the reader experience my point, instead of reading it. So a lot of my writing starts there: with the words themselves. For example, the very first note I have in my phone for SIGN HERE is Ruth’s line, ‘Do you ever just want to rip your nails through someone’s face?’ I had that thought (to be clear, it was a random thought, not a desire or intention!), liked the way it sounded and then started speculating: What kind of person would ask that question? What does it say about them and their internal world, especially if they are young and female? How would another person respond, and what kind of relationships would influence that response differently? Then I design characters in answer.

“With a character, I can explore what it would be like to be X type of person, or Y type of person, without any consequences to my real life. I’ve heard a lot of writers talk about how the characters do what they want and the writer is just along for the ride, and that hasn’t exactly been my experience, but it’s something similar. It’s more like letting out every facet of my personality for recess and seeing what games they come up with when left to interact together.

“One of my favorite memories from writing this book was one night, when I was wrapping up, I decided to write the first sentence of the next chapter, just so I could have something to start off with when I returned. So there I was, a little loopy from sitting alone in my study for hours on end late into the night, and I got this kind of cheeky, mischievous feeling, like right before you challenge someone to eat a pepper you know is super-hot, and I typed: ‘Calamity Gannon, human name redacted, got her taste for blood the first time one of her brothers beat another to death in front of her.’ Up to that moment, I didn’t have any plans for Cal’s background. But I wrote that insane sentence out of nowhere, pushed back from my laptop, threw my hands up into the air, and said out loud to no one, ‘Good luck figuring that out!’ It was like I was challenging myself; a jovial—and yes, slightly competitive—raising of the bar. The next night I sat down and kept going from that place, and now Cal’s background is some of my favorite content.

“I made a lot of my decisions like that: raising the bar, challenging myself, and ultimately having fun in the wacky playground of my imagination, letting whatever thought, however weird or unsightly or dark, have its time in the sun.”

Some of those decisions came from Lux’s professional background as well—she holds a master’s in social work from the University of Texas at Austin.

“I had this excellent teacher in my master’s program who taught Clinical Assessment, and she used popular films to help us learn how to diagnose clients, like What’s Eating Gilbert Grape and Taxi Driver. While some might consider using films in class to mean the work would be easy (like I did when I signed up for it!), Dr. Montgomery’s approach was the complete opposite: She challenged us to get into the characters, their environments, and their social systems before we wrote up our diagnosis, and always encouraged debate among the varying outcomes. Since that course, I have been low-key generating a syllabus of my own that essentially goes in the reverse: exploring how to use the theories and practices behind social work to create the most believable and fully human characters and relationships: the kind we connect with most deeply and miss long after the book is over.”

Is she still involved with social work today? “After taking care of my father through to his death in 2017, I decided I needed to take a step back from trauma work and focus on writing. But I became a social worker because I wanted to fight for good, and I felt like I was losing a huge part of my soul. I spoke to another social worker friend of mine, and she said, ‘Changing the world is a marathon. Just because you’re taking a break from running doesn’t mean there aren’t other roles that are just as important. You can cheer, train, pass out water. But if you run yourself into the ground, you can’t do anything anymore.’ So when I started writing this book, I did so with that marathon in mind. That is why I have included scenes that address domestic violence and child abuse. I know they can be hard to read—trust me, they were hard to write. But there is no room for resiliency, for the growth and progress born from turning fear into outrage into change, if we refuse to look. So, to answer your question: No, not at the moment. But at the same time: yes, always.”

Mention of her father brings up a great deal more about the influence of her parents. “As the child of a nonfiction writer and a poet—Jean Kilbourne and Thomas Lux—I was taught from a very early age that words contain so much more than their meanings. From childhood, my mother’s pioneering work in media criticism and feminist activism taught me how to observe and interpret the world, to recognize not only what is being said between the lines, but also the power of the things left unsaid. My father’s prolific career gave me an early and deep love of poetry, and appreciation for all the things language itself has to offer.

“I wrote SIGN HERE in the year or so after my father died, and I processed a lot of my grief through the characters in my book. There’s a strong father/daughter theme running throughout, and the incredible toll it takes on you and the people around you to miss someone like that. Grief is enormous and often ignored in our society because it is hard to look at. I found a lot of solace in writing this book—alone with my characters, I didn’t have to make my sadness more palatable for the comfort of others. For me, he is on every page.”

His influence is reflected in the publishing process, too. “The first time my dad read a short story of mine, we were sitting on these park benches at Sarah Lawrence, where I was a college student and he was a professor. When he finished, he put his hand on my shoulder the way he always did, holding me by the neck like a farm animal, and said, ‘I’m so sorry, kid, but you’ve got the sickness.’ It’s how he described the need to write; not the desire or the interest, but the need, the way that we need food and water and kin. He was being tongue-in-cheek; it was his way of saying he was proud of me. But he was also serious. Writing can be isolating, and not just during the act. When your job is to create people and worlds that feel emotionally authentic, it is through your relationships and interactions that you siphon said authenticity.

“As writers, we’re familiar with the ‘paper your walls with rejection slips’ concept, and that was very much my initial process. Back in 2014, I started my first book—a completely different book from SIGN HERE—and got incredibly lucky when my agent, Lucy Cleland of Kneerim & Williams, read it in 2017 and agreed to sign me. But even after working hard on that book together to get it into fighting shape, we were met with rejections. Kind rejections—even some encouraging rejections—but rejections all the same. So then I wrote another book, which I never even showed to Lucy because I knew it needed more work than I could ask of her, and then, finally, I wrote SIGN HERE. I edited that manuscript on my own for a year and a half, testing drafts on my friends and writing group before sending it in. Lucy submitted it first to Berkley on a Friday, and on Monday morning we got the call, asking for exclusive rights. It was my 34th birthday and to date, the best day of my life. At that point, I had been working full-time at other jobs and writing at night for seven years. I wish I could say I knew that eventually something would happen, but I didn’t. I just kept at it because I simply couldn’t help it. For better or worse, it’s my sickness.”

A sickness we are all happy to share! Lux is working on another book for Berkley—“in the same vein: the world as we know it, but one fundamental thing is completely different, and it changes everything. It’s also got a twisty mystery in there!”—and when asked if she had any final words, she doubles down on her appreciation for everybody who has brought her to this point.

“I’d love to reiterate how amazing it is to receive be able to talk about this book and my process like this: It is an absolute dream come true. I know that not all responses to my work will be positive, and I’ve made peace with that (just ask my therapist!). But knowing that these people I made up are out there in the world, in some way impacting strangers far and wide, is thrilling and humbling, and I couldn’t be more grateful. I’ve also been blown away by the encouragement I’ve received from other writers. From my writing group, who workshopped every page, to writers I’ve admired from afar supporting me as I approach this debut, the community has meant the world to me. And that includes everybody reading this piece! Thank you all so much. It has been an absolute joy.”

*****

Neil Nyren is the former evp, associate publisher, and editor in chief of G.P. Putnam’s Sons, and the winner of the 2017 Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Among the writers of crime and suspense he has edited are Tom Clancy, Clive Cussler, John Sandford, C. J. Box, Robert Crais, Carl Hiaasen, Daniel Silva, Jack Higgins, Frederick Forsyth, Ken Follett, Jonathan Kellerman, Ed McBain, and Ace Atkins. He now writes about crime fiction and publishing for CrimeReads, BookTrib, The Big Thrill, and The Third Degree, among others, and is a contributing writer to the Anthony/Agatha/Macavity-winning How to Write a Mystery.

He is currently writing a monthly publishing column for the MWA newsletter The Third Degree, as well as a regular ITW-sponsored series on debut thriller authors for BookTrib.com and is an editor at large for CrimeReads.

This column originally ran on Booktrib, where writers and readers meet.

- Africa Scene: Iris Mwanza by Michael Sears - December 16, 2024

- Late Checkout by Alan Orloff (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024

- Jack Stewart with Millie Naylor Hast (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024