Up Close: Kelly J. Ford

Real Bad Things Is Really Good

By Dawn Ius

By Dawn Ius

Where do you get your ideas from? It’s a cliché question and one most authors hate—often because they can’t remember, precisely, what sparked a story idea or why it became “the nugget” that carries the entire novel. But for award-winning author Kelly J. Ford, she knows exactly where her stories come from—they’re molded around distinct moments in her life she has either witnessed or experienced. The kind of moments that just “stick.”

“My debut, Cottonmouths, was a mix of unrequited queer love and the burgeoning small town meth crisis, which touched my family. I remember sitting at Grandma’s kitchen table as she worried a paper towel into shreds over a relative,” she says.

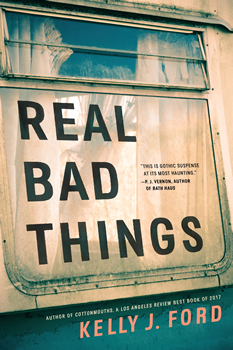

Her latest book, REAL BAD THINGS, takes her—and the reader—back to her childhood and a new worry.

“It was a different kind of worry, one I experienced as a kid in a household affected by domestic violence, substance abuse, and the accompanying neglect that can occur in those situations,” she says. “It’s this feeling of being trapped by your circumstance because you’re a dependent. That was my experience with one of my stepdads. Many times, I thought, I wouldn’t mind if that dude died. Somehow my brain coupled that with my lifelong fear of drowning, which I literally dreamed about last night. Those two terrors are the genesis of REAL BAD THINGS.”

The story centers on a decades-old murder. When Jane Mooney’s violent stepfather Warren disappeared, everyone assumed he got drunk and drowned. Instead of letting that rumor take root, Jane confesses to the murder. She wants to go to jail—but there’s no body, so the police can’t charge her with a crime. Jane packs up her secrets and heads to Boston for a fresh start.

But now, 25 years later, a body has been found, and Jane must return to her hometown to reckon with her past.

In this in-depth interview with The Big Thrill, Ford talks about her connection to Arkansas and small towns, the complexities of blended families, and navigating the long journey to publishing success.

REAL BAD THINGS—as well as your excellent debut, Cottonmouths—takes place in Arkansas, and in some ways (and not to sound cliché), the setting becomes its own character. What draws you back to Arkansas—and to small towns in general?

Arkansas holds such a strong place in my mind because it’s where I came of age. I didn’t leave the state until after college. Places like Arkansas, and small towns in general, make great settings because they’re pressure cooker environments for characters and for exploring class, sexuality, and circumstance. I moved around too much as a kid to belong to a small town in the way that many of my characters do. But as the ever-outsider in these environments, I spent a lot of time observing, like an anthropologist. Town dynamics are fascinating to me. Everyone knows everyone, and those people know your cousin or your uncle or your grandparents. Think of that one “bad” family. You say their last name, and everyone in town shakes their head because they have a picture of the family’s distinct generational trauma and often judge others solely because of that context. It’s often hard to escape these places. In a way, the town becomes another antagonist.

In the book, Jane confesses to killing her stepdad 25 years ago—and while I obviously don’t condone murder, I’d love to hear more about the inspiration for Warren, who sounds like he deserved it. While I know stepparents can get a bad rap, I grew up with a great stepdad, and I’m a stepmom I think my kid adores… What led you down the dark path here?

Every parent in a blended family who has interviewed me has mentioned this, and I think that fear speaks to the tangled and stressful nature of joining together such disparate, baggage-bound individuals into a family unit. My stepmom has been in my life for almost 40 years, and it’s been a positive experience. Obviously, that’s not always the case. Blended families are often rife with drama–and trauma. But in REAL BAD THINGS, I didn’t want to go the route of what you normally see in these narratives. Childhood neglect and emotional abuse are more prevalent in my stories because I’ve experienced it. Kids are often bounced between homes and harbor conflicted feelings that manifest in troublesome behavior. In many ways, I pondered what life might have been like in my own circumstance had I been face-to-face with a monster—in this case, my stepdad.

Ford takes part in the Boucheron Evolution of Noir panel with Christa Faust, S.A. Cosby, Peter Rozovsky, and Eryk Pruitt.

While the story is told from two points of view—Jane and Georgia Lee—it’s really about a group of four friends, all extremely well developed. How did you land on the two of them as the story’s narrators? And on that same thread, Jane emerges as a much more sympathetic character. Which one was more difficult to write and why? How much of yourself do you put into your characters?

Jane and Georgia Lee both existed as fully fleshed-out characters in two different manuscripts that I had decided to put away. The plots weren’t really clicking in either, but I couldn’t get these two characters out of my head. Jane carries a lot of sadness and guilt surrounding her brother and a crushing need for her mother’s affection. But she also has a dark sense of humor about her situation and a deep love for her brother.

Georgia Lee was actually a teenager in the other novel, but I could picture her as an adult, kind of a country bumpkin Tracy Flick from Election. She has this deliciously cranky sensibility that amuses me to no end, which makes her such a fun character to write. And she’s a great complement to Jane. With the sort of story I’m telling, I really wanted to have folks guessing not at who did what but considering the idea of truth and what constitutes a crime.

My characters are pieces of me, they’re pieces of people I know or have known; but they’re not me. Queer people, especially our trans family, live in an environment that repeatedly tells us we’re “not right” or “weird” or “disgusting.” There are real terrors to inhabiting one’s true self, including the fear of public opinion. So I hope that readers will come away from the book with a better understanding of why some characters may have a certain edge to them. Years of digesting that kind of input can create a hardness whose primary goal is to protect.

REAL BAD THINGS takes us down a twisty road—a true web of possibilities. The Big Thrill is as much for readers of suspense as it is for aspiring writers. What three tips would you offer on how to craft those twists and turns?

From the first pages of REAL BAD THINGS the reader learns that Jane confessed to the murder of her stepfather. So the mystery is more about unraveling the why. I’ve always been more interested in “why vs. who” narratives, maybe because I was a psychology major for a hot second in college. I like to know what makes people tick. I like to know their family context and what their turning points were, the events that either broke or saved them. I want to clear away the cobwebs to see what darkness they’re hiding. That said, twists and thrills do not come easy for me. I truly have to work at it. Things that have helped me are outlining, studying other novels whose structure I want to emulate, and beta readers/listeners/editors.

Around the third or fourth draft, I have a better sense of what my book actually could be. Before that, it’s just, well, vibes. But by the later drafts, I truly know the characters and place. At that point, I outline the book and go down a lot of “what if” routes to discover the “situation.” This sometimes means I write a lot of “off-the-page” material that never gets used, but I think it’s important to not only write those pages but also be willing to throw it all out if it’s not working with the story you want to tell.

Ford participates in a Boston Book Festival panel with Whitney Scharer, Gabe Habash, and Simeon Marsalis. Photo credit: Sarah Pruski

Secondly, it helps me to reread books that I think have a great structure that might be a good fit for my work in progress. I mark POV and structural shifts and make notes about characters or particular situations. Part of this process is reminding myself that things can be done. So often, writers are told something along the lines of “You have to have this happen at this percent of the book.” I think it’s useful to be able to point to successful books (which isn’t just sales, but acclaim) and show that a less traditional pace or structure can work, even within genre expectations. And it frees the head to be more creative with my own book.

Beta readers are critically important to me. I’ve had many over the years, but there are three voices that really help me to shape the book that I want to send to my agent: Elizabeth Chiles-Shelburne, writer of the gorgeous, devastating Southern debut Holding on to Nothing, helps me finesse my characters and make sense of my world. PJ Vernon, author of Bath Haus, is a plot master. I can call him up, and he will bounce all the ideas around with me. Talking through these things is so, so important to me getting a handle on the mystery. And most importantly, my wife, Sarah, lets me read my book aloud to her. She hears a lot of my plotting and talking, but she’s great at stopping me and telling me that something doesn’t make sense or if something feels flat.

Clearly REAL BAD THINGS is a novel of suspense, but it also tackles some important themes. Aside from a great read, what do you hope readers take away from this story?

First and foremost, I hope to entertain, but everything I write is filtered through a perspective that I don’t see represented as often in novels: queer, rural, working class. I’m not trying to educate, per se. If a reader comes away from my book with a better understanding of how neglect, food instability, and housing insecurity can affect individuals, then that’s just a bonus.

Ford (far right) moderates a Boston Book Festival panel featuring Desmond Hall, Marjan Kamali, and Elizabeth Chiles Shelburne.

There’s a wonderful level of authenticity in this book—the plot, the characters, the crime itself. What level of research, if any, was required as you write this book, and was there anything surprising you learned in the process?

As with most crime writers, I reviewed legal processes and procedures and the particular nature of deaths in my book, particularly as it relates to drowning in a lock and dam. And I spent a lot of time trying to ensure that the characters of Asian descent were accurately represented–mostly through the help of generous sensitivity readers. Though I set all my books in fictional towns in Northwest Arkansas, they are based on the places I’ve lived. It’s important to me to represent the world I grew up in on the page.

I wouldn’t say there was anything all that surprising that I learned. Like a lot of writers, I enjoy research, and the hardest part is not including every fascinating detail you find because it’s just plain cool, and you want to share that wonder with other people.

Your first novel, Cottonmouths, which came out in 2018, received well-deserved praise. Sophomore books can be tough, and to make things even tougher, we’ve been dealing with a pandemic for the past two years. How did you navigate your way through that to bring us REAL BAD THINGS?

Ford with fellow Evolution of Noir panelists S.A. Cosby and Christa Faust at Bouchercon. Photo credit: Peter Rozovsky

I’ve always had multiple jobs at once, so I’m used to juggling priorities. Whenever I finish one book (whether it’s a first draft or final, to my agent or to my editor), I begin work on the next thing. I’m always noodling on a story because I love to daydream, especially during workouts or while walking.

And my journey has been long. I’m certainly not an overnight success. I plugged away at Cottonmouths going on 20 years, with nothing but hope to fuel me. It took a long time to revise, get an agent, and sell to a publisher. When it did sell, it was more like a slow burn over several years. So I’m used to waiting; I’m a very patient person. I don’t like to rush things, and I don’t like to be rushed. Given that structured mentality, I didn’t have as much trouble getting into REAL BAD THINGS or other writing. The hardest part was trying to find the head space and time for writing as my technology day job responsibilities grew during the pandemic. But I also work for an amazing company and have the ability to work remotely and part time. Having so many deadlines probably helped me stay focused and not go too deep into anxiety with the world or self-doubt with my book.

There are a number of deliciously dark scenes in this novel. Without giving away any spoilers, or perhaps being a bit vague, what was the most difficult scene to write?

I love writing dark scenes and love scenes, probably because I read so many of my Grandma Sue’s old true crime magazines and Grandma Ford’s romance novels. The scenes that are hardest for me are the logistical ones, such as when one person needs to get to a different room, or I need to explain some plot point. I’ve often sat with characters and novels for so long that I assume my meaning is clear. I’m also often too subtle with my clues. But luckily, I have editors who are there to help me shore things up.

What did you edit out of this book that you wish you didn’t have to, if anything?

There’s rarely something left on the cutting room floor that hurts my heart when I think about it. The finished form of REAL BAD THINGS is truly the story I wanted to tell. Besides, if I love something I’ve written, I’ll find a way to use it in another novel.

What can you share about what you’re working on next?

I’m currently in the developmental edit phase for my third book, tentatively titled The Hunt. Of course, things can change significantly in this phase of editing, but the gist is that a small town stands divided as the local classic rock station prepares to host its first post-COVID Hunt for the Golden Egg scavenger hunt. Self-proclaimed “Eggheads” ready themselves for the largest payout ever, while anti-Eggheads rally against the Hunt and brace for the return of The Hunter, the alleged serial killer who has been using the Hunt as their killing ground for 17 years.

What does literary success look like to you?

When one of the actors or creators from A League of Their Own (TV series) posts one of my books on social media and says they love it. I’m a huge fan of this show and am experiencing legitimate sadness in its absence now that I’ve binged the whole season. Seeing your community represented on TV, and in so many dimensions, is a dream. I forget sometimes how hard it is when I finish something so queer-focused and then have to wait months or even years to have that same experience because our lives aren’t as visible in pop culture. To have a queer artist in a different medium love and appreciate your work? That’s the dream.

- Africa Scene: Iris Mwanza by Michael Sears - December 16, 2024

- Late Checkout by Alan Orloff (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024

- Jack Stewart with Millie Naylor Hast (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024