Crafting the Perfect Character Trifecta

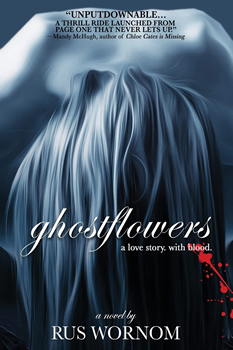

It’s the perfect character trifecta for a horror tale: a beautiful diner waitress, a mysterious biker that rides into town, and a crooked sheriff obsessed with his version of law and order. Set during the Fourth of July in 1971, the opening salvo of Rus Wornom’s GHOSTFLOWERS is the death of a small-town woman and the sheriff’s intention of pinning the crime on the recently arrived Vietnam veteran. This is a Southern horror thriller about the undead.

The setting is the fictional small town of Stonebridge, Virginia, nestled in the southwestern hills of Virginia. The locale is based on the author’s memories of Hampton, VA, portions of rural Caroline County, VA, where he worked at the newspaper for three years, and the Natural Bridge and Luray Caverns.

The novel was greatly inspired by the Dracula film series produced by Hammer Films, TV’s Dark Shadows, the original Night Stalker ABC TV-movie, and Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot.

Rus Wornom is an award-winning newspaper reporter who has been writing professionally since 1983, and GHOSTFLOWERS is his first published novel in 28 years.

The Big Thrill caught up with the author to talk about his horror debut, the challenges of setting a novel in the ’70s, and his lifelong fascination with scary tales.

Do you recall the exact moment when the idea for GHOSTFLOWERS formed?

This makes me smile every time I think about it. One morning in 1996, I was shaving, getting ready for work—I worked in advertising at a Virginia newspaper back then—and my wife surprised me at the bathroom door. She just looked at me with this crazed look in her eyes and said, “Why don’t you write a really, really bad book and make us a lot of money? Like—The Vampires of Madison County?”

Now, she and I were not fans of The Bridges of Madison County. No matter its then-bestseller status, which lasted for a considerably long time, we had read it, and while we could understand its charms with readers—especially older readers—we just didn’t think it was very well-written. So I stared at her for a few seconds and told her it was an awful, terrible idea, and I went back to shaving. By the time I finished shaving, I knew the names of the main characters, knew the story would take place in the summer in rural Virginia and in the early 1970s, and I knew how the book would end.

What can you tell us about Colonel Michel Trager—aka the biker—and Summer?

That morning while I was shaving, I knew he was named Michel—his identity as Trager came later during outlining—and that he was a biker who rides into town. Summer was originally named Cassandra, and she was young, 19 to 21, and blond. Unfortunately, I discovered a few years later that the main character of The Vampire Diaries was named Cassandra. I thought about how my main character, in my mind, embodied the brightest, warmest characteristics of summer in the South, and I realized there was no reason why her name shouldn’t be Summer. In fact, it was a better, more appropriate choice.

From the beginning, I knew Michel was the stranger and the antihero and Summer was the true protagonist. This was really her story; the stranger was the Mystery Man, and his backstory grew as I outlined the novel. Something in my subconscious wanted me to hold back in revealing his name, and when I was writing it, little things like that fell into place as Summer’s bond with Michel grew.

When did you know you loved horror stories?

Falling in love with horror was a gradual thing. The first movie I remember seeing was a horror movie, either The Frozen Dead or Ghidrah, the Three-Headed Monster, in the Langley Theatre in downtown Hampton, Virginia. I’m not sure which I saw first, but I remember watching both between parted fingers, and one was part of a live spook show where a monster kidnapped a girl out of the audience. So I was five or six. Before that, my mother had taught me how to read by using comic books, especially issues of Casper the Friendly Ghost. So I think I was a monster kid by the time I was three and a half.

The books I read in elementary school were the Alfred Hitchcock anthologies and scary books I bought from Scholastic Books. The days at school when the paperbacks arrived were the greatest! And then there was Dark Shadows. The show thrilled me as much as it scared the crap out of me. I loved the first movie, I got the comic books, I read all the semi-related paperbacks by Marilyn Ross (actually Dan Ross, I learned 20 years after the fact).

I don’t love all horror. I can’t watch a lot of the new movies or read a lot of today’s novels. I hate zombies, and I detest gratuitous gore. The horror I love falls under Stephen King’s three rules of horror: Blood must be spilled, the innocent must suffer, and evil must be punished. Let me add one more: I want the story to be fun. I hope I achieved all that with GHOSTFLOWERS.

A common description for horror tales is “atmospheric”—why do you think that is, and how do you achieve it in your writing?

Atmosphere isn’t just your novel’s setting, or the weather your characters have to walk through; it’s also how a writer constructs sentences to serve the purposes of the story. I think Lovecraft was one of the first horror writers to talk about the importance of atmosphere in a horror story. It’s all about a word I feel I use too much, but it’s a great concept: verisimilitude. You have to use every color in your art box to make a story seem real to the reader, especially if it’s a story about make-believe monsters. You have to develop an atmosphere of increasing dread to make your story of monsters and ghouls feel as real as possible. Think about all the modern movies we consider not only the scariest, but classics of the genre: Exorcist, Jaws, Alien, Poltergeist, The Shining—each of these still powerful classics exemplifies a feeling of increasing dread as their stories progress, and things get worse and worse for the characters.

How was the experience of researching the ’70s?

It was the most fun and the most thorough research that I’ve ever done. So I lived through the ’60s and ’70s and experienced a lot of what I put on paper. It was a joy going back and remembering things about my hometown and growing up that I hadn’t thought about in decades. Remembering the shoes I liked as a kid in 1971 and the shops we had. I put that all in the novel because Summer would have lived through the same things, too.

The music was especially important. Rock and roll coming through the car radio—probably the area’s popular AM station—and later, at night in your room, through a dime store stereo system—AM/FM radio, turntable, and 8-track player—was the day-to-day backdrop for our lives as teenagers back then. We only had three regular TV stations, and maybe four if you were lucky enough to get public TV on the VHF frequencies—and I knew it was my job to fully recreate this era for the reader without letting them drop out of the illusion.

When I started, I had no idea how much Vietnam would be involved in the back story, or what Michel did in the war, but a few hours of research on the Internet gave me the place names and the background that I needed to help flesh him out. I even got some help from my brother-in-law, Ed, who fought in Vietnam and told me what airport veterans coming from Vietnam would first fly into. LAX, it turned out.

I feel like doing all this research makes me a time traveler in a sense. That era in my mind is now just as real as it was when I lived it. The feeling won’t loosen its grip, either. In my head, I feel the breeze rushing through the car windows in the summer, because no one had air conditioning in their cars then, and I can smell the fresh mown grass on the wind, and taste the first sip of a Michelob, cold and sweating in a can; and the aromas of popcorn and burgers watching movies at the drive-in. I’m still there.

What was the most surprising thing you discovered during research, and were you able to use it?

Two things in my research surprised me, and I used them both. First, I was hoping that July 4th in 1971 would fall on a weekend, preferably a Saturday. That would tie in with what I needed in my narrative, and it worked out almost perfectly: July 4th was a Sunday. Good enough. Then, I needed to know what movies were playing that weekend at drive-in theaters. I went to the library and dug out the microfilms from hometown newspapers in 1971, and the BEST double feature was playing that weekend: Hammer Films’ Scars of Dracula and Horror of Frankenstein.

It could not have been more perfect!