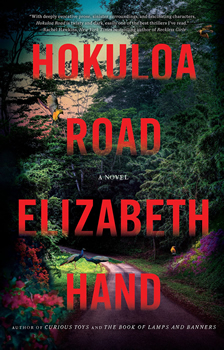

Up Close: Elizabeth Hand

A World Alive with Hawaiian Mythology

On a whim, Grady Kendall applies to work as a live-in caretaker for a luxury property in Hawai’i, as far from his small-town Maine life as he can imagine. Within days, he’s flying out to an estate on remote Hokuloa Road, where he quickly uncovers a dark side to the island’s idyllic reputation: It has long been a place where people vanish without a trace.

When a young woman from his flight becomes the next to disappear, Grady is determined—and soon desperate—to figure out what’s happened to Jessie and to all those staring out at him from the island’s “missing” posters. But working with Raina—Jessie’s fiercely protective best friend—to uncover the truth is anything but easy, and with an inexplicable and sinister presence stalking his every step, Grady can only hope he’ll find the answers he’s seeking before it’s too late.

Tension fills the pages of HOKULOA ROAD as we follow Grady into a world alive with Hawaiian mythology. It’s a world that is terrifying yet fascinating and will keep readers turning the page.

In this The Big Thrill interview, Hand shares further insight into the inspiration behind her compelling new thriller, HOKULOA ROAD.

Setting is such an important element in HOKULOA ROAD. How did you arrive at and develop the setting for this novel?

As a writer, I always start with setting in mind, even before character. I’m often drawn to bleak locations, and I found Maui, for all its beauty, to be a sometimes desolate and sinister place. It reminds me a lot of Iceland—a potentially unforgiving, volcanic landscape that I found really intimidating. My daughter lives on Maui, and for the last seven or eight years I’ve visited her and her family there. I’m a New Englander who’s lived in rural Maine for the last 34 years: To me, Maui wasn’t paradise. It was really, really unsettling.

In my fiction, I tend to run toward what unnerves me, and I knew from the first time I visited the island that I’d use it in a novel one day. In 2020, I spent six weeks there at the height of the pandemic—my daughter was having her first child. I quarantined for two weeks in their basement (as Grady does in HOKULOA ROAD, only he’s in his own little cottage).

When I re-emerged, I found the island transformed. The tourists were gone. People were out of work. There were extremely stringent COVID measures, the strictest in the country. All the resorts and hotels were shuttered. Without tens of thousands of tourists, one could be alone on Haleakala, or in the Makawao Forest. Some of the island’s wildlife and marine life began to rebound from decades of over-tourism. It was an incredible, surreal time to witness, and I knew that if I didn’t at least try to capture some of that in a novel, I’d always regret it.

In HOKULOA ROAD, you explore some of Hawai’i’s fascinating mythology. Can you tell us about your research process and how you managed to weave it into a modern story?

I’ve always used elements of folklore, folk wisdom, mythology, urban legends, and archaeology in my fiction. I love learning new stuff, so I just fell down a rabbit hole, reading as much as I could find in books and online, and also talking to people I know in Hawaiʻi. And I had several sensitivity readers who read early drafts and pointed out so, so many things that I had gotten wrong about Hawaiian culture and spiritual practices. I had a huge learning curve with this novel, and I still learned only a tiny fraction of what there is to know.

The main character, Grady, moves from Maine to Hawai’i. He’s the perfect fish out of water, and the reader sees the story through his eyes. Can you tell us more about him and where the inspiration for his character came from?

A few years ago, pre-pandemic, I had a conversation with my friend and MFA teaching colleague, the writer Susan Conley. We both live in Maine, we both have young adult sons, and we talked about the challenge of creating portrayals of decent, if flawed, men in fiction. Most of my recent fiction features female protagonists, so I took our conversation as a jumping-off point to create a white male cisgender character, a young, working-class carpenter who is totally out of his element and stumbles through a threatened environment and incredibly complex culture that are both totally alien to him. It was important that Grady not be a white savior figure, and I wanted his reactions and decision-making to be realistic and at times, deeply morally conflicted. But of course, I’m writing a thriller, so I have to balance that with action and a possible crime or series of crimes.

I also see many similarities between Hawai’i and Maine, Grady’s home state. Both places are beautiful, with imperiled and exploited wilderness areas. Both have a long history of white domination of indigenous peoples. Both have huge economic disparities, with people from away (Maine) and haoles (Hawai’i) exploiting housing and natural resources. Both have growing populations of working people who can no longer afford housing, especially in the wake of the pandemic. So while Grady is definitely a fish out of water, he recognizes and relates to a lot of these situations because he’s encountered them at home.

Do you write purely to entertain, or is there something larger that you hope readers will take from HOKULOA ROAD?

Hawai’i, like Maine, is a huge tourist destination. People save up for years, decades, to visit Maui as tourists—they have their weddings there, family vacations, anniversary trips, you name it. Often, they don’t venture far from the resorts, and when they do, it’s often via curated trips by rental car or bus to popular tourist destinations like the Road to Hana. Affluent people from the mainland buy second homes, further depleting the housing market (same thing in Maine).

On Maui, the major industry is tourism, and it’s obviously not a sustainable situation. There are droughts, wildfires, destruction of wildlife and human habitat by developers and resorts. Agribusinesses and cattle ranching have destroyed huge swathes of wilderness, though restoration projects spearheaded by Native Hawaiians are gaining traction in the islands. Almost 90 percent of Maui’s food is imported, which means it can be hugely expensive, and is highly vulnerable to supply chain disruption. Again, there’s a push by local groups for more food sovereignty (same in Maine). And there’s also the huge issue of restoring Hawaiian sovereignty (similar to that of tribal sovereignty in Maine).

Hawai’i has more extinct bird species than anyplace on earth: Since humans first arrived there about 1,600 years ago, two-thirds of the islands’ bird species have disappeared because of human intervention. Climate change has intensified this. In September 2021, the US Fish and Wildlife Service released a list of 23 species that are now extinct. Eleven of those are (were) in Hawai’i. “Hawai’i and the Pacific Islands are home to more than 650 species of plants and animals listed under the Endangered Species Act. This is more than any other state, and most of these species are found nowhere else in the world” [per the US Fish and Wildlife Service].

I’d like for readers of HOKULOA ROAD to end up with a sense of just how fragile, beautiful, and threatened a place Hawai’i is and how without positive human intervention, its wilderness, flora, and fauna could be lost forever. Not just Hawai’i: this entire planet.

Do you feel like there are any hard-and-fast rules that apply to writing thrillers?

I sure hope not—if there are, I’ve probably broken all of them! I think the same rules, if we can even call them rules, apply to thrillers as to other types of fiction. I do think there are techniques one can learn or develop. You want the reader to never put the book down—hard to do if you’re reading/writing a 400-page novel. Short chapters are a trick I picked up at some point, also ending each chapter on a cliffhanger. (I don’t always do either, but I try to keep them in mind.) Obviously, that can (and does) get kind of formulaic, but it works. I think the most important thing a writer can do is create a compelling narrative voice. It can be attached to a first-person narrator, as in Du Maurier’s Rebecca, or a series of close third-person characters, as seen in some work by Ruth Rendell/Barbara Vine and Atkinson.

Who are some authors or books that have inspired you in your career?

There are so many. When it comes to psychological thrillers and noir, I tend to go for books that are atmospheric slow burns and feature offbeat or obsessive characters, rather than novels that are primarily plot-driven. So: Scott Spencer, Ruth Rendell/Barbara Vine, Daphne Du Maurier, Patricia Highsmith, Peter Høeg. Smilla’s Sense of Snow was a huge influence, ditto Kerstin Ekman’s Blackwater. Johan Theorin uses folklore elements in his crime fiction in a marvelous way. (I still haven’t read Stieg Larsson’s work or seen any of the movies.) Ren Denfeld’s debut novel The Enchanted blew me away, as did her later novels. Just about anything by Kate Atkinson. I reread Susanna Moore’s In the Cut not long ago, and it’s as devastating—maybe more devastating—now than when it was first published in 1995.

I always hate this question because I later think of 50 other writers or novels I should have mentioned!

- On the Cover: Rijula Das - September 30, 2022

- Up Close: Daco S. Auffenorde - August 31, 2022

- Up Close: B.R. Myers - August 1, 2022