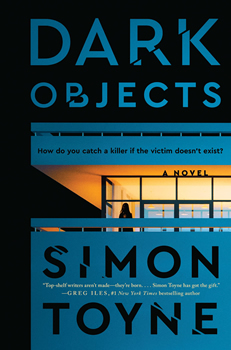

International Thrills: Simon Toyne

True Crime as Entertainment

People are murdered every day. These deaths are often background chatter in our lives, always present, though rarely acknowledged. Until something interesting happens.

Kate Miller was murdered. The story could end there, with the police showing up and carting the body away, a small headline on page four of the daily paper. But Kate wasn’t just stabbed to death—well, she actually was stabbed to death—no, Kate was arranged. Her body was deliberately positioned in her no-longer-pristine white living room in her security fortress of a house in London’s fancy Highgate neighborhood. And there were things around her. Things that didn’t belong there. Unusual things.

A stuffed unicorn toy placed above her head. Two old medals balanced on the index finger of her left hand. A ring of keys next to her right hand. And at her feet, a slim book: How to Process a Murder by Laughton Rees.

Professor Laughton Rees, that is. The estranged daughter of the Metropolitan Police Commissioner and an expert in murder investigations, a woman who has a strict rule of never working a live case; she has her own homicide-related trauma to deal with.

But her rule is challenged when the only lead in this bizarre murder is her book, as the victim isn’t who the neighbors thought she was. In fact, Kate Miller doesn’t even exist. There are no records of her life, no bank accounts, no job history, no fingerprints on file, nothing. Now the police have a corpse with no name, killed in a house no one should have been able to break into, whose body was arranged in a mysterious way, and the only person who has a hope of solving it doesn’t want anything to do with it.

In this exclusive interview with The Big Thrill, author Simon Toyne graciously allowed us to commandeer the entire discussion so we could focus on the deep undercurrents that flow through the background of DARK OBJECTS.

This book is excellent. I’m assuming you know that.

Well, thank you for saying so. There’s always that sense of “Is this working? Does it work?” I think every author at some point—certainly I do, normally in the first draft—gets to about 30,000 or 40,000 words in and suddenly goes, “Is this the silliest idea?”

The initial excitement that’s driven you forward, that’s gone. You burn that out. It’s like the first thrust of a rocket leaving, and then that burner thing falls away, and all of a sudden, you’re floating and you’re like, “Oh. I’m here now. Now what?” I hope I’ve got some more juice in the tank because otherwise I’m just floating.

There’s always that doubt, you know, and then you work on it, and it goes out and it gets published. You want people to like it. It’s a commitment to read a book, and you want people to not feel cheated by the fact that they’ve given me a chunk of their time to read this story that I’m telling them. That, at the end of it, they don’t feel like they want those eight hours back. I feel the responsibility there, and I do want to tell a good story. So yes, it’s very nice to hear, thank you.

I didn’t actually want to talk to you so much about the main thrust of the story, but the secondary themes you have running through your book.

POC teenager, Kai Mustafa, who was murdered in the same way, though under different circumstances. Kai is brought up repeatedly throughout the book, when the detectives are talking, essentially a “We’re focused on this white lady, but what about this kid?”

As that’s happening, we have this other mini-story with the Highgate Ladies Book Club, who are Kate Miller’s also wealthy white neighbors and are now deeply worried that they could be next, which we get to see through their WhatsApp group conversation, how they’re all reacting to the crime: their constant self-focused panic until they are able to shift the conversation to othering the victim by talking about how strange she was.

These scenes are always there, but their contents are rarely directly addressed by the various characters, so I wanted to understand and hear more from you about why you put these through-lines of racism and injustice in a book about a white lady getting murdered.

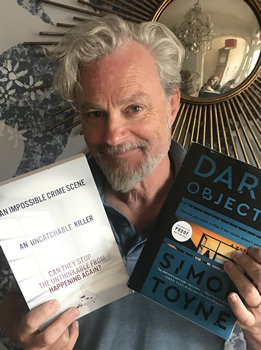

Toyne and author Karin Slaughter film an episode of Toyne’s true crime TV series Written in Blood in front of the Henry County Jail in McDonough, Georgia.

Part of the reason why it’s a white lady getting murdered is because there’s an interesting mirror to the central character, Laughton Rees, who is also a white lady. Because it’s ultimately Laughton’s journey that we’re following as she unravels the mystery of who murdered Kate Miller and why.

But yes, the idea of how some crimes seem to have a value or a currency to them. They seem kind of like more glamorous or more important, and yet it’s an identical crime, for all intents and purposes, where the stakes are the same: Two people die. And one is just utterly ignored. How does that work? But also the mechanics of how does that work—how does one get ignored and the other become a big thing? I wanted to kind of show how that works because we’re all kind of complicit in it as well. You know, we all watched the Johnny Depp and the Amber Heard trial—and even if you didn’t, that’s a choice as well. You’re sucked into these things and yet people have messy divorces every day and it’s like, well, why this?

Well, because they’re celebrities and because it’s salacious as well. There is much discussion of this in the UK, and of course there is even more in America, of this inherent unfairness of the justice system. It’s like you’ve got this VIP lane if you’re white and wealthy, but if you’re in a minority group and poor, then everything is starting against you. It’s not even like you’re on the same flight. It’s like you’re on a whole different plane that might crash and probably will. It’s not that you have less leg room, it’s a whole different deal.

Often, when you write a book, I think you’re trying to figure out what you think about something. I very rarely, if ever, set out going, “Oh, I think this thing about this subject, let me write a work of fiction that expresses what I think about the world.” Most of the time it’s more interesting, bearing in mind that writing a book takes a long time. There has got to be some kind of journey of exploration for me as well, otherwise you get bored. If all you’re doing is spending ages just putting down stuff that you’ve already figured out, you’re boring yourself because you already know it.

So the book is about injustice. The whole thing is about injustice. There are different examples of injustice that are told through the story. The different tiers of justice you get—or don’t get—through the judicial system is one of them. How you’re treated as a woman is another one, how you’re treated if you’re poor or rich, that’s another.

Going back to the ladies of Highgate, that’s why they’re there. Because they only really care about themselves. Initially they’re interested in what’s going on at the Miller house, and then they find out what’s actually happened. They’re shocked and display horror for about a nanosecond and then immediately are like, “Yeah, but they were weird,” and they start piling in on that and they distance themselves. As you say, they immediately start to protect themselves, to serve their self-interests.

That’s why things don’t change, because the people who have the money and the power, there’s no vested interest in changing anything or being outraged at these things. Because most of the time, it doesn’t touch them. In the book, I even go to the height of government, the Home Office—which is in charge of the policing system in the UK—and again, they’re only interested in votes. Who’s going to vote for us? Do we need to bother with this?

It was all of those things. But I never wanted them to be in front, partly because I am a white guy. Me suddenly making a whole book about something that loads of other authors who have much more to say and much more right to say those things than I do would write a much better book about that.

I wanted to talk about the relationship we as a culture have with true crime as entertainment. You’ve played it out so well in DARK OBJECTS, with both the Highgate Ladies Book Club and the rag The Daily, both of which help create an environment that feeds on itself by driving intense focus on this murdered woman. How were you thinking about that whole dynamic when you approached it?

Interestingly enough, part of the genesis of this book was that I made a TV series in the UK called Written in Blood, which I presented. I talked to different bestselling authors about the true crimes that had inspired their work. I went to them, and they’d tell me the story of the crime that basically fed into their own work.

During the course of that, one of the episodes had two things come out for me. One was exactly that question: What is it about crime and the fact that we are turning it into entertainment? It was something I wrestled with a lot because I was like, Oh, this is great, I’ll talk to loads of crime writers, what a brilliant thing to talk to brilliant storytellers telling brilliant stories, but you always know that what we’re doing is talking about people who died and people who went through terrible trauma and putting it on TV. I wrestled with that a lot.

We absolutely told the story of what happened; there was no reconstruction or anything, it’s just the investigation. I didn’t want to sensationalize it like a lot of shows do. I was very specific right from the off, that we were not doing that. It was more about talking about the story of it and the investigation. When the focus shifts to that, then you realize that the thing is with any story, the investigation and the people who ran the investigation, it’s as much their story as anyone else’s. There are some amazing, selfless acts. There would be one detective or a sergeant somewhere in the investigation who just decided that they would not let this one go. There were these amazing stories of ultimate justice, effectively. Which sold it to me.

That was one of the two things that surfaced. The other was a case in Glasgow in the eighties, where a couple of women were murdered in a month. In both cases—one was a minicab driver, and one was just one walking home—when their bodies were found, the contents of their handbags had been taken out and laid in a line next to the body. There was something about that, I thought, that was so weird. That’s the thing in this case that papers picked up on, because it was a sort of quirky detail. That was the thing that made the murders newsworthy when others wouldn’t be, because they had this macabre thing that felt fictional.

As we were recording that episode, one of the things that occurred to me was what one of the things we know, one of the detectives said, is that the last person who touched those things was the killer. A lot of times at a crime scene, you’re not sure where they trod or what they touched. Often, they may not even have touched the victim if there had been blunt trauma. But they knew for a fact the killer had touched these things and deliberately laid them in line.

There was something about that that sent a little sliver of ice down my spine. You can’t help it: As a writer, you just lock it away and go, That’s an interesting thought. Working backwards, who would have had that thought? Who would be thinking of how the killer had been the last one to touch those objects? That’s where Laughton came from, as an academic character who writes about things and explains the psychology and practicalities of a murder scene. Her book is found at this murder, and that’s how she gets sucked into it because she’s also the estranged daughter of the chief of police. And that’s newsworthy as well.

Part of what sucked her away was also the entrance of tabloid journalist Brian Slade and him diving into her life. One of the first things that happens after the book is found at the scene is she gets a call from Slade for quotes to feed into this machine that he works for, this machine that he’s joyously working for to sensationalize and drive clicks and eyes onto what sells with absolutely no ethics around it because he knows that society as a whole will respond to those things you’ve listed: a unique trait about the crime, a rich white lady, a murder in a very nice neighborhood, this book next to the body that was written by the estranged chief of police’s daughter who had a terrible thing happen to her when she was younger. He knows all of this will energize the story and knows the more sensational things he can put into it, the more attention he can receive, as long as he’s frightening or intriguing people.

He absolutely just sees all of this as commodity. It’s all commodity. He’s like a trader, but he happens to trade in sensationalism and misery. It’s funny. He’s a horrible character, and yet he’s the writer in the story. He’s the one who is making a living out of telling sensational stories and so, isn’t that what I do? Am I him? I mean, that’s the thing in all this. You have to be the bad guys. No one wakes up and thinks, “Am I the bad guy?” Or even if they know they’re doing bad things, they convince themselves they’re doing it for noble reasons. No one gets up going, “I’m going to be horrible today.” At least I don’t think so. When you’re writing these things, inevitably—even with the horrible characters—you have a kinship, and you have to find the humanity.

It all goes back to being a reader. I really like reading books where you have an opinion of a character and then it’s challenged at some point. You learned something about them which is surprising and softens you toward them or hardens you toward them or just makes you look at them afresh and makes you re-evaluate everything that you thought you knew about them.

I always trying to find the interest and the humanity in people. We’re all complex and messed-up, and we have our public persona, and we have our noble ideals. But we also know we can be crabby and release things and it’s more interesting to me as a reader and as a writer to add those layers to the character. To put something in there that makes you understand them a bit even if you still hate them. Understanding them makes them feel a bit more real.

Otherwise, you have these characters that are horrible for no reason. Even if you don’t agree with it, you understand it.

Toyne writes with one of his canine assistants, Woody, at his side. (Not pictured: assistant No. 2, Stevie Licks.)

I have two final questions. First, what do you hope people take away from this book? Either their experience of reading it or something you hope they pick up.

When I put a book out in the world, my anxiety and main hope is that I want people to enjoy it. I want people to go away and feel that they were glad they spent time reading the book—because they were entertained, diverted, it made them think about things. They were trying to figure out what the mystery was and either they did and feel pleased that they are so clever or didn’t and are enchanted by the fact that they didn’t.

Ultimately, I don’t want to write books that preach to people. I never want to do that. But I do think you can explore in a really interesting and useful way through fiction. Real life dilemmas, crimes, and things—it’s a safe way to look at it.

Last question, is there more for Laughton Rees? A sequel? A trilogy like you’ve done before? Are you thinking of a full series?

I have written it! Normally when a book comes out, I’m halfway through the next book, and I’m full of angst and it poisons it slightly because it’s supposed to be exciting because you’ve got a book coming out, but your head is full of the book you’ve been struggling with.

But this time, I am in the delightful situation where I have handed in a book called The Cinderman. Laughton Rees gets drawn into another case, and it’s set in the forest of Dean, which is an ancient forest two hours to the west of London. Women keep disappearing, and Laughton sees a pattern, so she goes to investigate.

I’ve really enjoyed writing her character. She feels to me like I didn’t really invent her. She just exists and is out there doing things. So I just write down what she’s up to. She’s small and flawed, and she’s got all kinds of weirdness going on, and she struggles. She reminds me a bit of an early career Jodie Foster character. She’s smart and underestimated, but very brave. Always brave. I love those kinds of characters.

- AudioFile Spotlight: March Mystery and Suspense Audiobooks - March 17, 2025

- Africa Scene: Shadow City by Natalie Conyer - March 17, 2025

- The Ballad of the Great Value Boys by Ken Harris - February 15, 2025