Up Close: Anne Heltzel

Motherhood Is a Cult

In Anne Heltzel’s adult horror debut, a young woman who managed to escape the clutches of a cult when she was a child falls prey to something even more insidious when she reconnects with a long-lost cousin.

Maeve, a single and struggling 30-something editor at a New York publishing house, has spent much of her life searching for Andrea, the cousin who once seemed more like a sister. Both girls spent a formative swathe of their childhood in the Mother Collective, a matriarchal cult whose twisted form of feminism held that a woman’s sole purpose was to bear and raise children. Maeve and Andrea spent years living in a remote compound surrounded by women whose identities were defined by motherhood—there was Mother with the lazy eye, for instance, and Mother with the blond hair to her waist. The only male presence was Boy, an infant whose gender meant he didn’t even deserve a name.

Maeve’s eventual escape brought the cult down and exposed its darkest secrets, and Maeve and Andrea were separated when they entered the foster system. Maeve has spent her life imagining countless versions of adult Andrea, but none of them come close to what she finds when Andrea finds her on a DNA testing website and makes contact: Andrea is the head of a successful startup devoted to helping women either prepare for motherhood or cope with the grief of losing a child. (Exactly how Andrea’s company does that is best left unspoiled.) When circumstances conspire to ensconce Maeve at Andrea and her husband’s remote Catskills estate, the book morphs from an eerie gothic chiller to a gory, gonzo horror show. Heltzel’s adult debut bodes well for her future as a horror writer—fast-paced and intensely atmospheric, JUST LIKE MOTHER is a fitting heir to reproductive horror classics such as Rosemary’s Baby and The Brood.

Heltzel, who is also an editorial director in the children’s division at Abrams Books and a former YA thriller author, recently made time for an in-depth talk about making the jump to adult horror, working in publishing, and finding a home at Tor Nightfire, the groundbreaking horror imprint that also published Catriona Ward’s The Last House on Needless Street and Gretchen Felker-Martin’s Manhunt.

Can you tell me a little about where this story came from?

The original germ of the story came from an experience that I had as a single person in my mid 30s. I had had a relationship fairly consistently, with only a few breaks for a couple of months in between, from the time I was 15 until the time I was 30. I was pretty much a serial monogamist. As such, I think I did start to measure my worth against my relationships. And so when I was single, after a pretty devastating breakup in 2015, it was just an awkward time to be single—everyone around me was coupling and settling down, if not already starting to have children. And I started to feel as though I’d missed some sort of profound message. I was operating under the pretense of this was really healthy for me, to finally have some time alone. But my timing was off, and everyone else had sort of gotten the memo that now’s the time to do this other thing.

That was a time in my life that was very necessary for me, because I did learn how to be happy and single. But also during that time I was living in a city where financial pressure was constant, and I started to think about how everything was lined up against me in terms of building a family. I didn’t know if I wanted one, but it was this sense of, even if I wanted to be a mother, I couldn’t because I now don’t have a partner and I can’t afford to be a single mom. And it just started to feel deeply unfair, and even kind of sinister. All of society is set up to support the family unit, but I had been blind to it because I’d never been in a position where I was forced to see it.

There’s this sort of canonical body of horror, both literature and film, that deals with reproductive issues—things like Rosemary’s Baby and The Brood—but most of the classics in that subgenre were written by men. Those stories are fantastic, but they’re missing a female perspective on matters that are deeply personal to women. Was JUST LIKE MOTHER a response to that in any way?

I hadn’t thought about that specifically, but that is an interesting point. I was definitely aware of a lot of women starting to write domestic thrillers. I felt like this was a slight departure from that, because it deals with what I started to call “fertility horror.” I wasn’t aware of anyone specifically digging into this one aspect of domesticity. And it was important to me also that it pushed past some boundaries. I love thrillers—I read thrillers all the time. And there are thriller elements to this, but I wanted to take it to a place that was darker and contained elements from the horror genre. But as for the involvement of men [in the subgenre], no, that was not on my mind.

But there was definitely, among people in my life, an initial reluctance to be open about the negative aspects of fertility—the traumatic births, the labor stories, and the ambivalence that seems prevalent, especially among women in my circle, who are all juggling a lot. I started realizing, wow, there are a lot of people out here who feel just like I do, who are completely ambivalent [about having children]. And that was so refreshing to hear, because I felt like a weirdo for not being certain and not having that maternal drive. It’s funny, because I didn’t really think about that directly until after I finished writing a draft. And then when I was pitching agents, I pitched it as The Haunting of Hill House meets Rosemary’s Baby, and that’s something that Nightfire has carried over into their own positioning, and other people have identified on Goodreads, is that there are some similarities to Rosemary’s Baby. But I guess I am glad to kind of reclaim that for women, and to speak about that anxiety from the position of someone who’s been there.

You mentioned writing a thriller that pulls in elements from the horror genre. I feel very comfortable saying that your book is a horror novel. But it also works as a thriller, and I’m wondering where that line is for you between thriller and horror.

I think psychological horror is truly, extremely dependent on what you, personally, are afraid of. So if someone is reading the book, and they are not personally afraid of these issues, they’re not going to find it horrific. But if I’m terrified of these things, doesn’t that mean I’m depicting a horror? I think the reason we can say this is also a thriller is because of the pacing. There’s definitely a certain structure that people associate with thrillers, and I think I naturally followed that pacing and structure because I read a ton of thrillers, and also, I wrote some YA thrillers. So just that setting up of tension, that rapid pace, is something I am intimately acquainted with. And it was just a natural part of the writing process for me. But psychological thriller and psychological horror, they’re both doing much the same thing. I do think there’s a little more freedom in horror to push it further and get a little more ludicrous, a little over the top, in a way that’s fun. And I think people who come to JUST LIKE MOTHER expecting a traditional thriller might be like, wait, what?

Things do get pretty crazy toward the end! I remember thinking it seemed like you were really having fun with it.

I had so much fun writing the last 60 or so pages of the book. I can remember that experience vividly. I wrote this book over a two and a half- to three-year period. I rewrote the first 100 pages probably a dozen times while I was figuring out what the story was. And in the last half to third, I was more confident and more secure in the voice of it. I do think the book suffers a little bit from the amount I rewrote it, but I don’t have any regrets because it was just a necessary part of figuring out this story.

But yeah, I wanted to really push boundaries with that last third. And that’s where I think the bulk of the horror elements come into play. There’s so much you can do—you don’t have to be realistic, and that was a lot of the fun of it. Giving myself permission to do that was a big step for me. I had a lot of fear in writing this book, just in terms of reputation, and people close to me who think of me a certain way—family and friends back in Ohio, and even just professionally, as a children’s book editor at Abrams—I had a lot of anxiety over going to this place. But now that I’ve done it, and people seem to be enjoying it, I’m gonna hopefully lean into it even more with my next one.

Why did you make the switch from YA thrillers to adult horror?

I never set out to write YA. I wanted to write middle grade first. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to sell my first book in the middle grade space, but I had a professor who encouraged me to write YA. I tried it, and I felt like I was trying to shove a square peg into a round hole. I never felt very comfortable there. I think I was trying to achieve things that weren’t a natural fit for me. Looking at reviews can be kind of dangerous for a lot of writers, but I personally don’t mind critical feedback—I’m strangely amused by some of it, and when you’re getting consistent feedback, it’s like getting a message from an editor that you need to work on something a little more. I’m able to take aspects of it and think, There’s a dozen people saying this, so there’s probably some truth to it. So in terms of reviews that I got on my YA titles, a lot of them were saying it was sort of adult crossover, that it was really gritty, and I thought, I’ve been playing it safe. I’m familiar with this business—I work in children’s books, and I know what people are looking for in this space, so I was definitely playing to a certain comfort zone. But I realized that if I really wanted to be authentic in my writing, I had to lean into this darkness that was a primary feature of my imagination, and I needed to just go all the way. The only way to do that was to [write in the adult category], because it’s no holds barred.

How do you think your work as an editor affects you as a writer? Do you ever feel like it gets in your way, or do you see it as an absolute benefit?

I consider it a benefit. It gets in my way in that it takes up a ton of time, but it’s a different part of my brain. I really consider myself lucky to be close to the industry, so I do get a sense of the submissions that come in and what people are talking about and looking for.

It’s much easier now that I’m writing adult, because when I was writing YA, I was concerned that I would subconsciously keep something in mind from a submission I received two years ago and maybe it would work its way into something I was writing. It was just too close. Also, I just knew too much about the business. I think there’s some degree of separation from the adult market and the way the adult business works, and it’s all new to me. That was both terrifying and exhilarating, and it’s been great. But as an editor, knowing how to structure a book, knowing how to plot a book, how to pace a book, feeling confident in that way, has been extremely beneficial.

And what about your experience as a ghostwriter? You did that for quite a while, right?

I did. I just got the opportunity sort of organically and I needed money, so that was a quick side gig. I did that for about four or five years, and then I felt like I had to put it aside and do my own thing. I was lucky enough to be approached with a couple of opportunities while I was in the midst of really digging into this, and it was difficult, at first, to say no to paid opportunities. When I was writing a thing that didn’t have a contract yet, and I didn’t know if it would sell, it was really hard to decline that money. But it was absolutely necessary to get this [book] done. I could have toiled away at some pretty low-paying gigs and not made much of a difference in my life, never given myself the opportunity to get my work out there.

That’s the trap you get caught in, isn’t it? Once you’re freelancing or working in publishing, the more experienced you get, the better you get at it, the more opportunities come your way, and those opportunities help keep the lights on, but they pull you away from the thing that you most want to do.

It’s very difficult. But it’s a privilege to say no, and getting those opportunities is a massive privilege. I was always really grateful for that. Having the ability to generate a side income while also moving forward in a career that I really love—there’s a lot to be said about that, like, why do I need to generate a side income for so long? But on the other hand, I always felt very lucky that I had this other skill set that I could utilize. It’s a massive risk writing anything, right? The amount of time you put into it, not knowing if it’ll ever be read—that’s a huge gamble, and I definitely was aware of that. But I also felt like I needed to make a gamble that could have a big payoff. And by “big payoff,” I simply mean that I would break into a new market and do something that was a challenge and completely unfamiliar. So I was doing something for myself, and it had a massive payoff for me in terms of just my own emotional space and confidence. I really, really do hope that anyone who wants to write a novel will give themselves time to do it at some point.

I don’t want to push this talk too far into political territory, but there’s something I’m curious about. JUST LIKE MOTHER tackles some thorny issues concerning types of feminism that are either exclusionary or expect women to fulfill certain traditional roles. This feels timely to me—there are elected officials whose views are widely considered misogynistic but who wouldn’t be in office without the support of women. When you wrote JUST LIKE MOTHER, how intentional were you about writing a feminist horror story where the villains aren’t men, but women who harm other women?

It was intentional, but I didn’t have an agenda. It was meant to take a closer look at the gray areas of, I guess, politics and feminism and the in-between spaces, and how women can be complicit in a male-driven agenda. There are many different types of feminism, and not all are created equal. And I guess what I became particularly fascinated by is we see a binary, primarily represented politically, where we see a lot of extremes on both sides. I am fascinated by the middle ground, in part because I lean liberal, but I grew up in Ohio. So I have a lot of people in my life who are not as liberal, who are closer to moderate or even right wing. I also went to a Catholic university for college. So of course, lots of people there [were more conservative] too. I do have some relationships in my life that have suffered because of that binary—[that attitude that] you’re one or the other, and you’re bad if you’re this or you’re bad if you’re that. Everyone is the enemy, right? But I grew up in this household with people whose intelligence I respect, people whom I love very much. And members of my immediate family did vote for Trump, and it’s hard for me to wrap my head around it. And I think the spaces in the middle, where things are not so clearly defined, where we can’t look at someone and say, Oh, that person is just totally the opposite of me in every way—that’s where it gets really interesting. When people are similar to you, but they’re going in different directions. That’s when it feels more insidious and a little more frightening.

And so specifically, to answer your question, I had one person in mind in later stages when I was writing the story—a former friend, who I had been very close to, who just went in a different direction from me. And this wasn’t the initial origin story of JUST LIKE MOTHER, but at some point, I realized I was writing about that relationship—someone I considered a sister, and then we essentially parted ways for 15-plus years. And then, in attempting to reconnect, I realized how different we had become. It was a little scary.

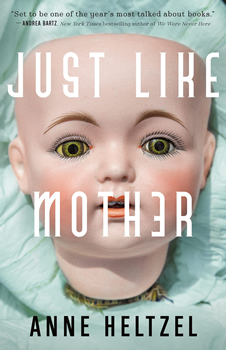

I never ask authors about their book jacket, but JUST LIKE MOTHER has such striking cover art—how did you feel when you saw it?

I was obsessed with it. I also, frankly, think it’s beautiful. I love the color—I’m a color fanatic. In my day job as an editor, I do have a say with the covers of the books on my list, and I often focus on how color works. That color scheme, to me, felt somehow beautiful despite the sinister imagery, and I loved it. We actually sat on it for a long time. Nightfire was awesome—they came up with multiple designs, and they pushed some designs really far. We came down to two covers, and one was very much like women’s lit. I was concerned that it wouldn’t find its audience. [Nightfire Senior Editor] Kelly [Lonesome], I think, liked both, and we saw the merits in both approaches. The concern was attracting a more mainstream audience, and everyone I asked, it was completely split down the middle. People in the industry, people outside the industry. A lot of people said some version of, I would never pick up that doll face. And in the end, I just went with my gut. I talked to my agent, and she was like, Let’s just go for it. I just liked that one, and it felt right to me. I wanted to make sure people knew what this book was.

Is there anything important about the book that we didn’t cover?

One thing that comes to mind: A lot of people have expressed frustration with the protagonist’s naivete. And then—and this is my fault, as a writer—a few people have gotten what I was going for with that, which is a depiction of trauma. To me, from a psychological perspective, it makes sense that someone who grew up in the type of environment that she did that Maeve would not really know what’s good for her and what to trust and would have instincts she doesn’t follow because she wants something so badly. That was my aim. I think people who grew up in situations that are not healthy as children often don’t trust their own instincts. That’s a big part of it, and a lot of Maeve’s journey is about learning to really trust herself and take control of her own life. I hope that, in the end, it comes across that way. If there’s ambiguity in the beginning, that’s my fault as a writer.

It never struck me that way. She grew up in a cult, after all. Speaking of, did you do a lot of research about cults going into this?

Honest, I didn’t. I’ve watched some documentaries, but that was more for pleasure. This did not start off being a cult story. It really started out as a story about these two women who reconnect and have this conflict, but I wanted to take the book to a place that was more distinctly creepy. I had experimented with flashback scenes for early drafts that I had not shown my agent. I wound up feeling very strongly that I wanted a real glimpse into Maeve’s psychological backdrop. So I brought some of those scenes back, and my agent really liked them. I reworked them, and even still, those were not cult scenes—they were just Maeve’s childhood flashback scenes. And then later, I was really worried that people would somehow link this back to my own mother, if I focused on Maeve and her mother and a traumatic childhood. I wanted to give myself distance, and I wanted there to be no mistaking that this was like purely fiction. And around that time, it also just kind of clicked: Motherhood is a cult. No one asks questions, we all are complicit, we just do this thing and follow what someone else decided for us. It felt like a cult. And then it just occurred to me, why not have many mothers? That makes so much sense. And it’s funny—I did not want to detract from the present action, so I don’t have a lot of flashbacks. I wanted to keep this minimal. I actually added more in revisions than there were originally, but some people feel that story would have been better served by more explanation. I can see that, and I would not be opposed to writing a prequel or something that really explores the foundations of the cult—it is interesting, it’s just not what the story set out to be. Getting into one of the mother’s heads and seeing how she got into the cult and how she became “Mother with the lazy eye”—it’s fun to think about. Hopefully I’ll have the opportunity to do something like that.

Can you tell me anything at all about what you’re working on now?

I’m in the thick of a new manuscript for Tor Nightfire. Hopefully, it’ll be out next year. I don’t know for sure. I don’t even know if I should say this, but the working title is Ripe Old Fruit. Without getting into plot mechanics, it deals with a fear of aging. It has another gothic setting, but in New York City this time.

- Africa Scene: Iris Mwanza by Michael Sears - December 16, 2024

- Late Checkout by Alan Orloff (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024

- Jack Stewart with Millie Naylor Hast (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024