Up Close: Alma Katsu

A Demon for Every Temple

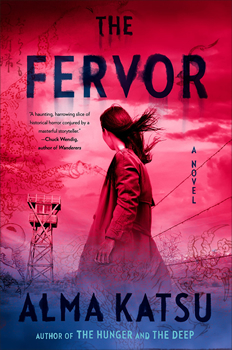

It only took two novels—2018’s Donner Party-inspired The Hunger and 2020’s Titanic-themed The Deep—to establish Alma Katsu as the reigning queen of historical horror. After veering into the spy genre with last year’s Red Widow, Katsu is back in familiar territory with THE FERVOR, a horror novel set against the backdrop of World War II, when 120,000 Japanese Americans—tens of thousands of whom were American citizens, many born on US soil—were forced out of their homes and placed in concentration camps.

The novel centers on Meiko Briggs, a Japanese American woman who, along with her young daughter, Aiko, has been confined to an Idaho prison camp while her Air Force-pilot husband fights in the Pacific theater. When a mysterious illness known as “the fervor” sweeps through the camp, and Aiko claims to receive ominous warnings from spirits and creatures from Japanese folklore, Meiko takes it upon herself to investigate camp officials’ increasingly strange and secretive behavior. Meanwhile, an Oregon minister who was widowed by a mysterious explosion is haunted by a kimono-clad apparition and sightings of tiny, translucent spiders, and a Nebraska reporter ditches her married boyfriend to chase a story about fiery objects spotted in the skies across the western US.

Unlike her previous historical horror tales, THE FERVOR is intensely personal for Katsu, who is of Japanese descent. As she writes in the book’s afterword, her mother was the target of anti-Asian racism when she immigrated to America decades ago, and Katsu’s father-in-law was interned during World War II. It’s the first time Katsu has written a book with an Asian main character.

In her latest interview with The Big Thrill, Katsu talks about telling her story from a diverse range of perspectives, giving herself permission to take some liberties with the historical timeline, and writing a historical horror tale that became disturbingly relevant as she wrote it.

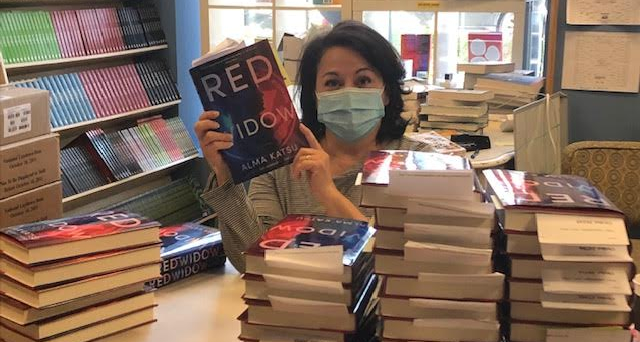

How did it feel to return to historical horror after writing your (Thriller Award-nominated) spy novel Red Widow?

As much fun as I had writing Red Widow, going back to historical horror was like slipping into something comfortable. By the third book of this type, I have a routine down: research, outline, writing. It’s not all pre-determined; surprises and unexpected bits come up while putting the words on page. Those characters love to surprise you.

This is obviously a very personal story for you. How was your family affected by the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII?

My mother was born in Japan. She married my father after the war and came to America. While she wanted us to be proud of our heritage, she was also subjected to hostility from Americans who had lost someone in the war, and those experiences made her reticent to call attention to herself. In writing this book, I realized that her experiences stayed with me, too, quite strongly. Then I married into a Japanese American family that had been interned. Up until this point, the internment was something I’d heard about but not something I’d experienced personally. Listening to my in-laws’ stories and watching documentaries, I learned that the internment was not as cut-and-dried as we’d been told.

People who lived through the internment generally don’t like to talk about it. They hold their memories at arm’s length. Some would only talk about it cheerfully, possibly because they feel compelled to put a good face on what was a shameful and punishing experience. Shame and embarrassment of this magnitude—even if you were innocent, contributed in no way to crime for which you are being punished—leave deep scars in a person.

Why is now the time to tell this story?

I’ve learned from writing these books the truth behind that old adage, if you fail to learn from history, you’re doomed to repeat it. When Asians in America started to be attacked in 2020 following politically motivated allegations that China had deliberated leaked the coronavirus, it seemed eerily familiar. Did you know that the Executive Order that put Japanese Americans into the camps was rescinded in 1944, but many internees were afraid to go back, fearing violence from neighbors? That violence had been fanned by decades of open racism from White nationalist groups that targeted Asians. The [White nationalist group] Loyal Sons of the Republic in my book is modeled on the Native Sons of the Golden West, whose members believed California had to be protected “as a paradise of the white man for all time.”

This story is incredibly relevant to what’s happening today, but surely you didn’t conceive and write the entire thing in the last two years. When did you start it, and how much did it change during the pandemic?

I worked on the proposal in the fall of 2019. THE FERVOR wasn’t intended to be about the pandemic: it was modeled on the hostility and anger that was dividing this country and meant to address the resurgence of racism that we’re experiencing. As things progressed, both on the disease front and on the political front, I adjusted the story because it was intended to be allegorical: to show what happened in the 1940s is happening again today.

What’s the most surprising thing you learned or came to realize while you were researching and writing THE FERVOR?

I was shocked at how widespread and pervasive these White nationalist groups were in the 20th century. These groups, whose main targets were Chinese and Japanese, were active in the western United States, and they’d been operating openly and aggressively for decades.

Katsu with podcast hosts Laura and Dave Medicus at Tattered Cover in Denver, Colorado, for the release of 2020’s The Deep, just days before the US went into lockdown.

THE FERVOR involves several figures from Japanese folklore, including creatures known as yōkai. How did you first encounter those stories?

We grew up with Japanese picture books. It was just a peek into the very rich and complex world of Japanese demons and ghosts. It seems sometimes that, in Japan, there’s a demon or ghost for every temple or crossroads. Having said that, it’s also interesting to note the similarities between European and Japanese fairy tales. Urashima and the Turtle shares some elements with The Little Mermaid. Peach Boy strongly resembles its European doppelganger Thumbelina.

You approach history differently in THE FERVOR than in The Hunger and The Deep; for instance, with THE FERVOR, you allow yourself to take more liberties with the timeline of certain events. Why is that?

While THE FERVOR is like the first two books in some ways, it’s different in that this time, it’s not pinned or dependent to a specific historical event. While there are a couple specific historical events in the books—such as the explosion of the fu-go [Japanese balloon bomb] on Gearhart Mountain, which opens the books—the story here is meant to have its own a purpose and theme. It’s meant to tell a story that doesn’t exactly mirror the way things happened in the 1940s.

Do you think historical horror or fantasy gives us an opportunity to reconsider or explore history in a way mainstream historical fiction doesn’t?

Absolutely. That’s going to ruffle some purists who think no liberties should be taken with history, but that’s the point of fiction. To imagine. I think it’s especially useful with history because, as we’re seeing at this point in time, we’re learning that maybe we should question the way history is being framed and presented to us. Maybe the views we’ve been fed all these years aren’t the only valid perspectives. Maybe they’re even wrong.

The story is told through multiple points of view: a woman who immigrated from Japan; her father, who has never been to America; her daughter, who has never been to Japan; a White male minister, and a White female reporter. Why was it important to tell the story from so many perspectives?

These different perspectives tell different parts of the story. For instance, Archie, the minister, represents the Whites who not only let the internment happen but who chose to see their Japanese neighbors as threats even though they knew they weren’t. You could try to show that through Meiko, the Japanese character, as she comes to understand Archie, but it wouldn’t be as impactful. Even the daughter, never having experienced life in Japan, has a different perspective from her mother. As for Fran, the reporter, the story needed input that comes from outside the internment camp, things Meiko couldn’t learn while inside the camp.

Which character was most challenging to write, and why?

Meiko was the most challenging but also the most satisfying. It was the first time I got to write a major character of Asian descent, and I was surprised at how it felt to slip into that character. I was able to give voice to a lot of things I’d kept hidden away. I channeled my mother a lot for Meiko, especially in the early drafts: all her hurt at being attacked when she first came to America, right after the war. Her distrust of Whites. These are all very private feelings, and it’s hard to let them come out.

What’s one thing you wish more people knew or understood about the internment of Japanese Americans?

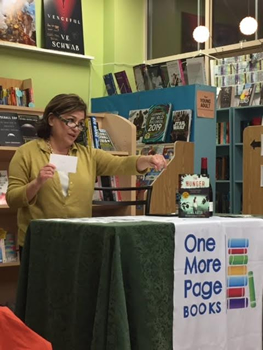

Katsu often plays a short game of Jeopardy based on the relevant historical event while on book tour. In this photo, she quizzes readers about the Donner Party tragedy, which inspired 2018’s The Hunger.

When it comes to history, too often we’re just given a sound bite. For the internment, we’re told that it happened because Americans were afraid that the Japanese in America would support Japan if America entered the war by spying or committing sabotage. But that’s only a part of the story. History is rarely that simple or straightforward.

In this case, FDR and the War Department conducted several studies before Pearl Harbor, and each study concluded that the Japanese in the US were not a national security threat. And yet he signed EO9066 because the public demanded it. And why was public sentiment against Asians so strong? It was because of decades of outspoken prejudice against Chinese and Japanese immigrants. Because White nativist groups had long denigrated Asians, demonized them, and sought to deny them the right to become citizens or own property. After the war, studies showed that not one case of espionage or sabotage was attributable to a person of Japanese descent. The entire internment effort was unwarranted (not to mention unconstitutional). The politicians who had pandered to the public and whipped up fear were dead wrong.

Can you share anything about what you’re working on now?

I’m doing the final revisions to Red London, the second book in the Red Widow espionage thriller series, which will be coming out in 2023. And then I’m working on the proposal for the next historical horror novel. I haven’t signed a contract on it yet, so the details are still under wraps.

- Africa Scene: Iris Mwanza by Michael Sears - December 16, 2024

- Late Checkout by Alan Orloff (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024

- Jack Stewart with Millie Naylor Hast (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024