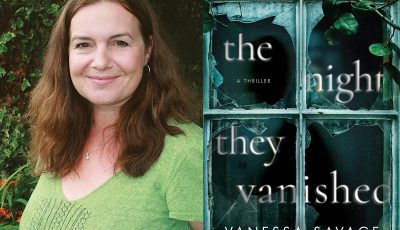

International Thrills: Vanessa Savage

The Fascination of Dark Tourism

By Dawn Ius

By Dawn Ius

Vanessa Savage used to write books with an expected Happily-Ever-After—but her fascination with the darker side of humanity led her to write crime fiction.

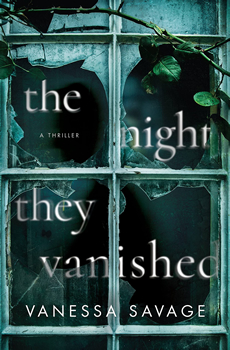

Her debut, The Woman in the Dark, was set in a notorious “murder house,” which allowed her to explore the idea of trying to make a home in a location everyone was interested in, not always for the right reasons. Savage’s exploration of “dark” locales continues in her chilling sophomore release, THE NIGHT THEY VANISHED.

In it, a young woman, somewhat estranged from her family, finds her childhood home on a Dark Tourism site, listed as a place where a tragic triple murder has happened. The disturbing part is, her family still lives there. At least, she thought they did. But when she tries to contact them, the house is empty, her family…vanished.

This is not the first tragedy to rock Hanna’s world—and in her quest to find out what happened to her family, she’ll need to confront not only her past, but the person determined to make her pay for it.

Here, the South Wales author talks more about her fascination with true crime, dark tourism, and family dynamics, and why these themes continue to make it into her thriller writing.

In the past few months, I’ve seen a number of thrillers with “family” at their core—THE NIGHT THEY VANISHED certainly fits in. What do you think is driving this trend?

I think in the last couple of years, as the whole world dealt with a global pandemic, our daily lives were forced to become smaller, and family—whether that’s family in the traditional sense or family as the people we love most—became our whole lives as we were locked down together, or, in many cases, separated from for far too long.

This book has such a fantastic hook. I’d love to hear more about the inspiration for the story.

My first novel, The Woman in the Dark, focuses on a family who move into a notorious “murder house” and have to deal with the curiosity of strangers as they attempt to make a place of tragedy into a home. As part of my research for that novel, I became fascinated by the idea of dark tourism, and it sparked a series of “what if” questions that wouldn’t go away until I began writing THE NIGHT THEY VANISHED—what if you found your family home listed as the site of a terrible murder on a true crime website? And then you can’t get hold of your family, they’ve vanished into the night… This branched out into—what happened the night they vanished? Where is the family? Who listed the house on the website? And why?

Dark tourism—tourist locations identified as places where death and / or suffering has occurred—is a bit of a booming industry, I’ve learned. In your book, Hanna learns of a horrific crime, potentially about her estranged family, on a website devoted to dark tourism. What kind of research did you do to write this book, and was there anything that surprised you?

Considering the ethical side of dark tourism was interesting. My instinctive reaction to the idea of dark tourism is, why are people fascinated by it? Why would anyone want to visit these sites of suffering and tragedy? But when researching the subject, I found that sites such as Auschwitz and the 9/11 memorial site can be viewed as dark tourism destinations, and I hope that people do not go to these sites in a voyeuristic way. People go there to learn about and understand the tragic history of the site. We need to understand our history in order to prevent such things happening again.

THE NIGHT THEY VANISHED also takes a look at society’s fascination with true crime. Aside from a compelling read, what do you hope readers take away from this book?

I think it gives the reader an insight into society’s fascination with true crime and dark tourism—and the similarity with our interest in reading crime fiction! When we read a crime novel, we’re interested in solving a puzzle, in indulging in the adrenaline rush of fear in a safe way—experiencing and learning from shocking crime without ever being in danger ourselves. We get to face our own fears—by confronting and understanding that fear, its power is taken away. We want to learn from and understand what happened so we can ensure we’re never in that danger ourselves.

You juggle multiple POVs, which are all clearly defined and well-developed. Whose were the most difficult to write, and why?

It was probably harder to write Sasha’s POV—to get into the mindset and discover the voice of a teenager when my teenage years are decades behind me. I have teenage daughters which helped as I am a daily witness to the experiences that make them happy or that trouble them, and they were invaluable in helping with the practical details—how teenagers speak, interact, what they’re studying in school. Although Sasha isn’t a typical 14-year-old, a lot of a teenager’s fears, hopes, and insecurities are universal.

I read on your website that you started your career writing women’s fiction. What drew you to crime / thriller writing?

I started out writing women’s fiction, character-driven fiction that was all about the lead up to the happy-ever-after. But the more I wrote, the more I became fascinated by the darker side of my characters. Relationships—whether romantic or familial—are at the heart of my writing, and for me, a psychological thriller is the flip side of a romance novel; it’s what happens after the happy-ever-after moment, how a relationship breaks down, how a friendship can spiral into paranoia and obsession… that’s what fascinates me as a writer. In real life, I’d much prefer the happy-ever-after.

As with your previous novels, you don’t shy away from dark themes. What was the toughest scene in THE NIGHT THEY VANISHED for you to write, and why?

Writing crime means exploring the darker side of life, often putting a character through terrible things… but that doesn’t mean I relish doing this. My characters become real to me, so it’s always hard to make them suffer. It’s also difficult to make my characters flawed—to have them make mistakes that you know will have repercussions. Even as I’m writing a scene, I can be inwardly screaming, “No, don’t do that!”

A lot of this is related to tension—a character needs to change over the course of a novel, and change occurs when things happen to them. And with a crime novel, the assumption is that the things that happen are going to be bad. It doesn’t have to be—it would be pretty bleak if all the characters go through unrelenting misery, but there have to be peaks and troughs, highs and lows, action and reaction. At each of those highs and lows when I’m plotting, I need to make something happen. Sometimes it’s obvious what needs to happen to further the plot, but sometimes a reaction or quieter scene can be just as effective—to give both the reader and character breathing space. A quieter reaction scene followed by something more high octane can make that follow-up scene all the more devastating.

THE NIGHT THEY VANISHED is a taut thriller—I love how “tight” the writing is. What did you edit out of this book? What advice would you give to writers looking to tighten their prose, and why is it important?

I planned out this book in quite a lot of detail—the storylines of my two main characters began several months apart but needed to converge at the climax, so planning was essential to ensure the characters reached certain points in their stories at the right time. This planning helped a lot, but there are always parts of a first or second draft that need editing out! I usually write quite a short first draft, a bare bones story, so the second draft is about adding and expanding. This is where my editing out happens, and it’s usually because if I have a scene or interaction I love and enjoy writing, I spend too long on it, and it upsets the balance. The third draft is where I go through and ask the question of every scene—do I need this? Does it progress the story? If it doesn’t, even if it’s some of my favorite writing, I’m merciless in cutting it out. I always keep what I cut in another document—sometimes elements will find their way back in.

What is your writing kryptonite?

It used to be planning! I used to think I couldn’t plan a book, I had to write my way into it and let the characters do their own thing and just see what happened… The problem was, what happened was a very saggy middle with a lot of directionless characters wandering around not sure what to do next. It was like me dumping my poor characters in the middle of a city they’d never visited before and just leaving them to it. I’ve since learned that by giving them a map and telling them their destination, the journey is easier and far more interesting.

What can you share about what you’re working on next?

I’m currently halfway through writing my next thriller! Here’s a little teaser…

Twenty years ago, in a small village, on a street at the edge of nowhere, a little girl disappeared. Suspicion fell on Cass, her teenage babysitter, and although the child was never found and no charge was ever brought, that taint of suspicion has remained…

Today, Cass is still living in the same house on the same street; the oddball, the hermit, the woman you cross the street to avoid.

And now, another child has gone missing.

- Africa Scene: Iris Mwanza by Michael Sears - December 16, 2024

- Late Checkout by Alan Orloff (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024

- Jack Stewart with Millie Naylor Hast (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024