CHAPTER 1

“I’m not trying to kill myself.” Though his expression was flat, Nigel McGowan’s color—at least how it appeared on my laptop screen—was whiter than the wall behind him.

“I’m not trying to kill myself.” Though his expression was flat, Nigel McGowan’s color—at least how it appeared on my laptop screen—was whiter than the wall behind him.

How many times have I heard those words? Another patient had sworn the same to me only two days before, during my week- end on call for the Anchorage Regional Hospital. That patient had begged me to free him from his involuntary confinement in the ER. But the raw ligature burns around his neck—from where the noose had yanked the hook free from the ceiling at the last moment—were far more persuasive than any of his pleas.

“You’re not suicidal,” I said, focusing back on Nigel. “You just don’t want to extend your life any longer than necessary. That right?” “Exactly right, Dr. Spears,” he said, as sweat beaded along his receding hairline.

Having seen the worrisome images of Nigel’s swollen, red-and- black blistered foot and shin, I was surprised he was upright at all with such an overwhelming infection snaking up his leg and into his bloodstream. “All right, Nigel,” I said. “Say I dove to the bottom of a swimming pool and decided not to extend my life by resurfacing. Wouldn’t that make me suicidal?”

He crossed his arms and rested them on his bulging belly. “That’s a silly comparison.”

“Is it, though? You’ve had uncontrolled diabetes for years, and you still refuse to take insulin. It gave you a heart attack before your fortieth birthday. And now you’ve got an infection that, according to your own doctor, will cost you your leg—probably your life—unless you agree to go to hospital for intravenous antibiotics.” I pointed at the screen. “Make no mistake, Nigel. You’re killing yourself. You’re just doing it slower than most.”

“I’m of sound mind. And I don’t want medications.” His damp lip quivered. “It’s my choice.”

He was right. I had no legal grounds to certify Nigel and keep him involuntarily in hospital for treatment—unlike my patient who’d tried to hang himself—even though his life was in the same degree of jeopardy. That conundrum made my temples throb. “And in my example, Nigel, it would be within my rights to stay underwa- ter until I drowned.”

Nigel swiped the sweat from his brow with the back of his hand. “This isn’t helping.”

“Help?” I stared intently at his wan face. “Since when do you come to me for help?”

His image froze on the video chat screen momentarily, but his words were still clear. “What kind of psychiatrist talks like that?”

“I’ll give you this, you’re one of my most reliable patients. Over three years, and I don’t think you’ve missed an appointment yet. But in that time, when have you ever taken my advice?”

“You mean your drugs, don’t you?”

“No, Nigel. Advice. For years, I’ve been begging you to come join group therapy. To join any group at all.”

“Group therapy?” He huffed. “For an agoraphobic?” “You’re not agoraphobic.”

“I have a pathological fear of rejection.”

“As we’ve discussed, that’s not agoraphobia.” Besides, techni- cally, it was a single rejection he kept reliving. Six years after being dumped by his then boyfriend, he was still grieving the breakup of a relationship that had only lasted months. “Let’s say you don’t die, Nigel. How do you feel about living with only one leg?”

“I hardly ever leave my apartment anyway.” But the quick flick of his eyes betrayed his anxiety.

“And then when you lose the other leg? You OK with not leav- ing your bed, either?”

He eyed me dolefully. “Where’s your compassion, Dr. Spears?”

Nigel had a point. A casual observer might have assumed I was taunting my own patient. But I saw no other choice. Pity was the one card Nigel relied on. It gave him a sense of control. He used it to handcuff the few people in his life who still cared about him, in- cluding me. And I knew from previous experiences that sometimes only harsh boundaries—even the threat of abandonment—would motivate him to comply.

“Enough of this manipulative crap,” I said. “I’m calling an am- bulance and you’re going to go to the hospital. Right now!”

“I won’t go.”

I held his gaze. “If you don’t, Nigel, I’m firing you as a patient.

And you and I will have no further contact. Ever.” His eyes went a bit wider. “You can’t do that!”

“Yes, I can,” I said. “Don’t worry, though. I’ll find you another psychiatrist. One who will be far more sympathetic to your plight. You can tell him or her all about how Gary abandoned you while the gangrene creeps up your leg.”

His voice faltered. “Please, Dr. Spears ”

I stared back at him, not giving an inch. His life hung in the bal- ance. “It’s your call, Nigel.”

His image froze again, for longer this time. When the screen came back to life, his chin hung low, but he was nodding.

“It’s the right choice, Nigel.” I offered a reassuring smile. “This is what we’re going to do: I’m going to hang up now and call the ambulance. And I’ll see you at the hospital later.”

Before he could reply, I ended the videoconference with a click of the mouse, partly because I wanted to dispatch the ambulance right away but mainly because I didn’t want to leave any wiggle room for him to renege.

I picked up the phone and dialed 9-1-1. The dispatcher con- firmed an ambulance would be arriving at Nigel’s apartment within minutes.

As I dictated the note into his electronic medical record, I re- flected on the pros and cons of virtual medicine, which had become so prevalent, especially for us psychiatrists, in the post-COVID world. Had Nigel been in my office, he might have had time to tell me he’d changed his mind while waiting for the ambulance. Then again, if we had been sitting face-to-face, connecting with one an- other’s physical presence, maybe it would’ve been much easier to convince him to go to the hospital in the first place.

It was the paradox of virtual medicine. Psychiatrists needed to see their patients. Visual cues were often more important to us than words. And the widespread availability of videoconferencing made remote consults possible. But while virtual care offered all the con- venience in the world, it also lacked the immediacy and intimacy of a one-on-one session, missing all those intangibles that could never transcend the screen. One day, some brilliant neuroscientist was bound to identify the alternate hot spots in the cerebral cortex and various pheromones that respond to human proximity. More than likely, some researcher already had.

But an in-person visit wasn’t an option for my next patient. She lived almost a thousand miles away, beyond the Arctic Circle, in the northernmost town in North America: Utqiagvik—formerly known as Barrow—Alaska. For Brianna O’Brien, like my other patients who lived in a town that was only accessible by air, virtual care was their sole option, apart from my biannual visits. I tried to get up there in the spring and again in late summer, and my trip for later next month was already booked.

I clicked the invitation icon on my laptop, and Brianna’s head appeared, framed by reddish-blonde hair that extended beyond her shoulders. With her makeup-free, heart-shaped face and her gray- ish doe-eyes, Brianna looked closer to fifteen or sixteen than the twenty-two-year-old she was. She wore the same black T-shirt— emblazoned with the words “Fuck the Police!”—that I had seen at previous sessions, but I didn’t recognize her backdrop, which looked to be the interior of a trailer or an RV. Usually, during our sessions, she sat in her small but always immaculate kitchen.

Brianna nodded her greeting, her mouth set in the ambiguous Mona Lisa smile that I’d come to expect from her.

“Hi, Brianna. Where are you?” “At a friend’s.”

“Where’s Nevaeh?” Usually by now, her adorable four-year-old daughter would have popped into the frame and peppered me with rapid-fire questions.

“With my aunt.”

Her inquisitive child resembled my Ali, in looks and personality, when my daughter had been about the same age. Nevaeh’s absence only reinforced how I much I was missing Ali this summer. My sixteen-year-old had chosen to stay in Seattle with her mom to at- tend an intense dance camp instead of spending the month of Au- gust with me in Anchorage. Or, at least, that was how my ex-wife had justified it.

“How are you doing today?” I asked.

She ran a hand through her hair, pulling away loose strands. “I’m OK.”

I picked up on the hesitance in her tone. “You sure?” “I still feel kind of fuzzy, I guess.”

“Since you started the new medication?”

“Maybe, yeah.”

“That’s normal. The side effects with Ketopram are always worst in the first month. And they’re usually gone by the end of the second.”

Brianna accepted my explanation with a twitch of her shoulders. “And your appetite?” I asked.

Her screen flickered for a second or two. “It’s OK,” she said. “And what about your thoughts, Brianna?”

Her gaze drifted away from the camera. “They’re . . . quiet.” I found her choice of words curious. “Quiet how? Peaceful?” “Calm, I guess.”

“How are you sleeping?”

“Not great.” She bit her lip and then added, “But I never really do.” “Some people get vivid dreams when they start taking Ketopram. Are you experiencing those?” “Just one. But I keep having it.”

I flashed an encouraging smile. “Can you elaborate?” “It’s a nightmare, not a dream.”

“Can you describe it to me, Brianna?”

“Me and Nevaeh are in my car,” she said softly. “She’s in her booster seat in the back, playing on my phone. We’re not moving. It’s really gray outside, and I can’t really see through the window. At first, I think I must be parked in a dense fog or something . . .”

I gave her a few moments to finish, but she only picked at a few more loose hairs. “But it’s not fog?” I prompted.

She sunk lower in her seat. “That’s when I see the drip coming from the corner of the driver’s window. Then the window cracks, and freezing water gushes inside. And just then—when I realize we’re underwater—I wake up.”

“You mean like submerged? Under the sea?” She nodded.

“How did you end up there?” “Don’t know.”

“In this nightmare, you didn’t deliberately drive into the water, did you?”

“No.”

“Do you ever fantasize about harming yourself, Brianna?” “Nevaeh was in the car, too!” Her voice cracked.

“How about without Nevaeh?” I asked softly.

She shook her head. “I’d never leave my daughter alone in the world.”

Brianna had rarely been even this forthcoming with me in the four months since I’d started seeing her. I didn’t want to stretch the bounds of her trust, so I didn’t push further.

Her family doctor had been treating Brianna with various anti- depressants on and off since he’d diagnosed her with a delayed postpartum depression. I recognized early on in our therapy that Brianna was still suffering from a major mood disorder. Since the antidepressants she had been taking hadn’t worked, I’d switched her over to Ketopram the month before. The groundbreaking drug, which had only been on the market for the past two years, had proven effective on other patients with refractory depressions that failed to respond to other antidepressants. Including my own.

“How about your overall mood?” I asked. “Are you finding more enjoyment in things?”

“Maybe? I mean, you know, with Nevaeh and all.” I chuckled. “That kid is something.”

“She’s everything,” Brianna said with a blank nod. “I’m crying a little less, too.”

“Soprogress, then?”

“Yeah, maybe.”

Her tone was too unconvincing to leave be. “Is there something else, Brianna?”

She opened her mouth and then stopped, dismissing it with an- other shrug. “I can’t remember the last time I laughed.”

“Laughed?”

“A belly laugh, you know? Like when you can’t stop giggling with your girlfriends. Used to do it all the time. Before the depres- sion.”

Brianna had a way of describing her depression as a single sud- den event, like an earthquake hitting, instead of an evolving medical condition. I had probed before, trying to find a specific precipitant for her despondency beyond the postpartum hormones, but she in- evitably would clam up.

There were still so many pieces of Brianna’s life that were miss- ing for me. Areas that remained taboo. I knew hardly anything about the father who abandoned her family when she was young or the oil field worker who’d fathered Nevaeh. In an earlier session, Brianna had blurted something about a man who’d taken advantage of her while she was still in high school. But she backtracked almost immediately, and I wasn’t able to unearth any more details. I hadn’t pushed too hard, aware it would take a lot of time and patience to get her to open up about any trauma.

With some patients, I could establish therapeutic intimacy in a single session—with others, it took years, if ever. Brianna and I were nowhere near that point. And in my experience, each patient required an individual approach to getting there. As much as Nigel often needed a strong hand, Brianna responded best to a softer approach. I’d seen how quickly the wrong line of inquiry or even a single question could shut her down for an entire session.

As we only had thirty minutes booked for this appointment, I used the remainder of our time to emphasize the nonpharmaceutical remedies that we’d discussed before to complement her medication, including exercise and sleep.

As the session was ending, Brianna bit her lip and viewed me with uncharacteristic inquisitiveness. “Will I ever get back to being me again, Dr. Spears?”

“You will. It’ll take time. But you will.”

“Time Yeah, OK.” She dug her fingers through her hair again

as if sifting through sand. “Dr. Spears?”

“Yes?” I surreptitiously glanced at the clock at the bottom of my screen. It was five minutes past the hour, and I could see my next patient had already logged into the virtual waiting room.

“It’s just that . . . there’s . . . I don’t know ”

I could see she was struggling to put something into words, but I was distracted by the time-warning light that was now flashing on my screen. So instead of trying to draw what she wanted to say out of her, I said, “Let’s pick this up on Friday, all right, Brianna?”

Not once did I suspect those would be the last words I ever spoke to her.

CHAPTER 2

“My phone pinged with another text from my friend, Javier Gutiérrez. “Late night,” it began. “Make mine a quadruple shot.” I’d forgotten that it was my turn to pick up coffees, which was going to make me even later to meet him.

I stood at my sink and glanced at the pentagonal pink pill between my fingers. I understood that pharmaceutical companies designed their tablets with such distinct shapes for various purposes, including ease of swallowing and to promote absorption at certain levels in the gut. But I also knew it was mainly a marketing ploy to hook doctors and patients on the pill’s unique look.

I popped the tablet in my mouth and washed it down with a quick gulp of water. I’d been taking the medication for over a year and a half, which made me one of the earlier Alaskans to start using Ketopram outside of the clinical trials. I no longer experienced any side effects, but the first month had been rough. The fatigue and heartburn hadn’t bothered me nearly as much as the intense dreams. They weren’t exactly nightmares, but they were far from pleasant, often centering around my dead parents, full of the imagery of loss and loneliness, such as the hospice bed on which my dad died. The kind of dream where you are thrilled to see a lost loved one but somehow know, even in the moment, that none of it is real.

I stuck the cap on the bottle and shoved it back inside the vanity, aware that even if all the side effects—including those melancholic dreams—had persisted, I would have continued to take the medication. It saved my life.

I pulled on my shoes and hurried out the door of my condo, onto the elevator, and out onto Fourth Street, where the sun was already high at eight in the morning and would remain so until well after midnight.

One of the things I appreciated most about living in Anchorage’s downtown core was that I hardly ever needed to drive in the summertime. I could walk from my home to my office or even to the hospital in under twenty minutes, which alone would have made the move from our old house in the residential Hillside East neighborhood worthwhile. Besides, staying alone in that big empty house, surrounded by nothing but bittersweet memories of Beth and Ali, would never have been an option. I couldn’t imagine a quicker path to insanity.

Jogging down Fourth Avenue, I was sweating by the time I reached Steeps, my favorite coffee shop. The heat was building, well into the seventies, and I had little doubt we were heading for another record high for late July. If only climate change deniers would come to Alaska, they wouldn’t even have to go see our rapidly receding glaciers. The near tropical temperatures in Anchorage alone should be enough to convince them of the foolishness of their beliefs.

Nicky, the chatty barista whose arms and neck formed a tapestry of tattoos, predicted my order down to the extra shots for Javier and had me back on the road in minutes. The two large coffees slowed me down, but I only had two more blocks to go until I reached the staircase leading down to the beachside trail.

The Tony Knowles Coastal Trail was easily Anchorage’s most popular summer destination for tourists and locals alike. With good reason. The eleven-mile paved pathway hugged the city’s western shore along the Cook Inlet. The trail offered stunning views of the downtown harbor, framed by the Chugach Mountain Range to the east. And on clear days like today, there were several spots to get a peek of North America’s highest peak, Denali, that floated ethereally two hundred miles to the north.

Javier and I often walked the trail. Occasionally, if we had time on the weekends, we would complete the whole eleven-mile route that ended in the massive oasis of nature within the city limits that was Kincaid Park. Today, we were squeezing our walk in before work, so we would likely have to turn around once we reached Earthquake Park. I wondered what the point of such a short walk would be, but Javier wouldn’t have let me cancel. He liked to keep close tabs on me. Both as my friend and my psychiatrist.

Dressed in stylish active wear with a Yankees ball cap pulled tightly over his thatch of jet-black hair, Javier paced at the bottom of the staircase. Fifteen years older, leaner, and a good two inches taller than me, Javier resembled a character actor whose name I didn’t know but who often showed up as a distinguished, Latino political leader or business executive in the thrillers I liked to watch. Fiercely proud of his roots as a third-generation Hispanic Alaskan, Javier sometimes jokingly referred to himself as a “native A-latin-skan.”

“Morning, David.” He greeted me with a short burst of his distinctive machine gun laughter. “Guess I’m going to have to settle for an ice coffee this morning, huh?”

“Sorry, Javier, time got away from me,” I said as I handed him the cup.

Javier uttered a satisfied sigh when he took the warm cup from my hand. “Shall we?” he asked as he set off down the shoreline trail at his usual rapid clip without waiting for a reply.

The breeze off the water brought a welcome coolness, which helped explain why the pathway was so crowded with walkers, joggers, and cyclists on a weekday morning.

“So?” he asked as I caught up to him.

“So . . . ?”

“How are you, David?”

“Fine.”

“How are you sleeping, eating, et cetera, et cetera?”

“All good, thanks.”

He flashed an exasperated smile. “Spoken like a patient truly withholding.”

“It’s been eighteen months, Javier. I’m back to myself now. And besides, I’m not your patient anymore.”

“Now you sound like one in full denial.”

Technically, Javier was correct. I was still his patient. And since it had been less than two years since my hospitalization, he was required to complete a form for the state medical board every month attesting to my fitness to practice. I hadn’t seen him in his office in almost a year, but our walks were a hybrid between two close friends catching up and a mental wellness check, even if they were skewed heavily toward the personal rather than the professional.

“If only the pool of psychiatrists were a little deeper in this town,” I said with a roll of my eyes, “I wouldn’t be trapped in this pointless cycle with you.”

“What about dating?” Javier asked, ignoring my dig.

“What about it?”

“When are you going to start?”

“Who has time?”

“Two years since you and Beth split up, right?”

“Roughly, yeah.” I had to bite my tongue not to point out that it had been just over twenty-seven months.

“I think you might’ve exceeded the statute of limitations on faithfulness. Especially since you weren’t the one who left.”

Beth might have been the one who had moved out, but I had no doubt who was to blame. In retrospect, I’m not sure why she hung in as long as she did. Beth had been right when she told me that I had shut her out “like a stranger.” My depression might have explained my mood, but it didn’t excuse my attitude. I couldn’t have been much colder or more irritable with her. After twenty years together, beginning as med school sweethearts, I owed her more. I regretted how I’d treated her. And I still missed her.

“Look at me, David.” Javier clutched his chest. “Maria’s been gone for just over six months, and I’m dating up a storm.”

“You never really liked Maria in the first place.”

“That’s not true. Well . . . not entirely. She was more of a transitional wife.”

“Have you nailed down the fourth one yet?”

Javier let off another burst of laughter. “No, but I’m auditioning like crazy.”

“No doubt you’ll find crazy, too.”

A Rollerblader whizzed past as the trail took us southwest along the mudflats of Kinik Arm, which offered a dramatic view of the mountains across the narrow passage.

Deliberately changing the subject, I said, “I admitted a guy on the weekend. He tried to hang himself.”

“And?” Javier shrugged. For a psychiatrist, admitting a suicidal patient while on call was as routine as a surgeon hospitalizing someone with appendicitis.

“This guy was already on antidepressants,” I continued. “In fact, Ketopram.”

“You sure he was taking it properly?”

“Blood test showed his drug level to be therapeutic.”

He shrugged. “Show me a drug that is a hundred percent effective against anything.”

As much of an advocate as I was for Ketopram, Javier was more so. He was the reason Alaska was an early adopter and one of the leading consumers of the medication per capita anywhere in the world. He had gone to school with the scientist who created Ketopram by adding an extra ring or two—I could never keep the biochemistry straight—to the familiar molecule of serotonin reuptake inhibitor contained in drugs such as Prozac. Javier lectured to colleagues statewide on its benefits, for which he was paid handsomely by its parent company, Pierson Pharmaceuticals.

“Just thought you should know,” I said. “Seeing as how much stock option you own in Pierson.”

“I’ve been begging you to buy in for the past three years, David. The stock has gone through the roof.” He held up his palms. “Then again you only have to support one ex-wife, and she has a decent-paying job.”

I chuckled. “Unlike your harem.”

“My defunct harem. Can I help it if I’m only attracted to projects?”

I felt my phone vibrate in my pocket, but since I wasn’t on call, I ignored the call. “That patient who tried to hang himself, Javier. He told me the dreams—visions as he called them—were driving him nuts. That he couldn’t take it anymore.”

“We both know those are only temporary, David. They always abate with time.”

“He has been on Ketopram for over two months, though,” I said. “Have you heard of any others?”

“Treatment failures on Ketopram?”

“Or suicide attempts?”

He looked out toward the water. “You know as well as I do that it’s a risk for any antidepressant.”

It was true. Patients were most vulnerable to suicide attempts in the early stages of treatment with antidepressants, when their energy and motivation had begun to improve but their mood was still depressed.

“So there have been others?” I asked.

“A couple of sporadic cases reported. Yes. Tragic, but nothing unexpected.”

Javier stopped without warning. He pulled his phone out of his pocket and pointed it toward the clearing off the side of the pathway. That was when I noticed that a moose was lazily grazing on the long grass about fifteen feet from us. There was nothing unusual about sighting a moose along this trail, but this one was as majestic as I’d ever seen, standing at least six feet tall, not even counting his prominent antlers. He gazed in our direction as he chewed, without showing the least fear. The sight reminded me again what a unique city and state we lived in.

After taking several shots with his phone upright and sideways, Javier slipped it back into his pocket and resumed his brisk walking pace. “David, I don’t want to get ahead of myself. But la amiga from last night . . .” He whistled. “She could be the next Mrs. Gutiérrez.”

“Well, we know one thing for sure—she won’t be the last.”

That set off a longer burst of Javier’s laughter. Once it passed, he asked, “How’s Ali?”

“Good. Very good. She won’t be spending August here, though.”

Javier’s face fell. “Why not?”

“Beth enrolled her in some intensive dance camp in Seattle that goes most of the summer.”

“What a shame. The only reason I spend any time with you the rest of the year is so I can see that delightful kid of yours in the summer.”

“Tough.” I chuckled. “At least we’ll still get our annual father-daughter road trip at the end of August.”

Two summers ago, months after Beth and I separated, Ali and I had flown to Hawaii together. I splurged on a spectacular resort on the Big Island, but it was Ali’s first vacation without her mom, and she brooded for most of it. I wasn’t in much better shape. Last year, though, we had had a lot more fun touring Provence, where Ali fell in love with French art and history, refusing to skip a museum or gallery anywhere we went.

“Where to this year?” Javier asked. “Machu Pichu? Petra? Or perhaps straight to Atlantis?”

“Even better,” I said. “I’m flying to Seattle and renting a car. Ali and I are driving up to Vancouver and then east from there through the interior of British Columbia—absolutely spectacular terrain, if you haven’t seen it—and over to the Canadian Rockies. I’ve already booked hotels in Banff, Jasper, and Lake Louise. Ali’s going to love it!”

“It’s not like you’re going to suffer, either, David.”

“I only hope I don’t miss one of your weddings while I’m gone.”

“Fifty-fifty.” He smiled.

We reached Earthquake Park and turned back for downtown, lapsing into conversation on the way back that ranged in topics from his mother’s gourmet cooking to local politics. Javier and I said our goodbyes at the base of the same staircase where we had met. Once alone, I stopped to check my phone. I’d missed two calls, both from Dr. Evan Harman, one of the three family doctors who practiced in Utqiagvik.

Despite the warmth of the sun, a chill spread through my chest, and my fingers went numb. I had to lean back against the railing of the staircase.

Evan and I shared care for several patients in the town, but somehow I knew he had to be calling about Brianna. And the news would not be good.

CHAPTER 3

“I stared at the blank screen, fighting off the dread while working up the nerve to call Evan back. Though he was based over seven hundred miles away in Utqiagvik, I’d come to know the rural family doctor relatively well over the past four years. We spoke at least once a month to review care plans on our patients. About a year and a half ago, we’d switched from phone calls to videoconferences, which had tipped our relationship into what felt like a friendship.

Everything about Evan struck me as casual, from the dark jeans and wrinkled polo shirts he wore to work, to his messy mop of dark hair that always looked at least a month overdue for a trim. I also respected him highly as a physician. Not only was he up to date and knowledgeable, but he stayed in close touch with his patients. His insights into small, day-to-day changes in their lives proved invaluable to me. And I had no doubt that our patients benefited from our collaboration.

But my fingers were trembling as I reached for the mouse and clicked the icon to initiate a video call. Moments later, Evan’s rugged face, handsome despite the sunken eyes and acne-scarred cheeks, appeared on my screen. Normally, he would have answered with a warm greeting and, usually, a corny joke. But his expression was as deadpan as his tone when he said, “Hello, David.”

“Sorry I missed your call, Evan.”

“Brianna O’Brien is dead,” he said, as if her surname were necessary.

Even though his words were confirmatory, my breath caught in my throat. “How?” I croaked.

“Carbon monoxide.”

“Jesus . . .”

“It could have been worse, David.”

I was speechless.

“Nevaeh was in the car, too,” he continued.

“Is she . . . ?”

“She’s all right. She’s with her great-aunt and -uncle. But she was in the backseat of the car.”

“What happened?” I croaked.

“Brianna was drinking last night. Sometime, after midnight, she must’ve carried Neveah in her sleep out to the garage. She put her in the booster seat, plugged her phone into the radio, and turned the engine on. She even placed a rock against the accelerator.” He stopped to clear his throat. “Her playlist was still going when they found her.”

The horrific vision filled my brain. I imagined Brianna gently lowering Nevaeh into the car so as not to wake her. I could see her kissing the girl’s forehead, closing the door, and then climbing into the driver’s seat. “How . . . how did Nevaeh get out?”

Evan squeezed his temples between his thumb and forefinger. “The cops assume Nevaeh woke up at some point. Must’ve been early on. Otherwise the carbon monoxide would’ve gotten to her pretty quickly. Maybe she tried to wake her mom, but between the alcohol and the fumes . . .” He shook his head. “Nevaeh shut the garage door behind her, and at some point wandered over to her great-aunt’s house. By the time they found Brianna . . .” His voice cracked. “Apparently, she always taught Nevaeh to close doors behind her.”

The idea that the four-year-old inadvertently sealed her mother’s fate by doing just what she was taught broke my heart. My eyes misted over, and I leaned away from the camera to wipe them with the bend of my elbow. “Did she leave a note?”

“No.”

“I had an appointment with her only three days ago,” I said more to myself than my colleague.

Evan grimaced. “I saw her just yesterday. She never even hinted . . . She told me things were getting better.”

Never trust the word of the actively suicidal! one of my favorite professors used to preach to us during training. It was a proven fact that those who were most determined to kill themselves were often the least forthcoming about their plans. But all I said was “She fooled us both, Evan.”

“Goddamn her!” he moaned. “To include Nevaeh? How could she have not said anything?”

My mind darted back to my last session with Brianna, analyzing the details as if watching a movie in slow motion, while scouring it for verbal or nonverbal clues.

“Did she mention her dream to you?” I finally asked.

“Dream? As in one of those Ketopram dreams?”

“Yeah. A recurrent nightmare. About drowning in her submerged car.” I swallowed. “In the dream, Nevaeh was in the car with her, too.”

“Nothing like that. No.”

“Brianna promised me she would never try anything. Especially not with Nevaeh.” My gaze fell to the keyboard. “I believed her.”

“I saw her yesterday, David! Just a handful of hours before she did it. If anyone is to blame . . .”

“You said it yourself, Evan. She was drinking. No note. It was probably a spontaneous decision.” I didn’t really believe that, but he looked as desperate for reassurance as he must have thought I was.

“Probably.”

“Will you let me know if you find out anything else? Toxicology reports and that kind of stuff? And, of course, any updates on Nevaeh?”

“Will do.” His voice was hollow.

“Evan, there are times when no one can predict suicide.”

“I hope this was one of those times.”

I prayed it was. “Let’s talk again soon.”

After I disconnected the call, I fought the overwhelming urge to call my ex-wife. Beth had seen me through the worst outcomes in my career. As a colleague and a natural empath, she had a way of putting events into perspective when I couldn’t. She would’ve known how to numb the searing pain and angst.

Instead, I opened the last note I had written on Brianna’s electronic chart. “Cautious and withholding today—not unusual for Brianna,” my words read. “Revisit her use of the term ‘quiet thoughts’ at a future session. She still requires close surveillance,” I had concluded, without an inkling of how fateful those words would prove.

Had Brianna already decided on what she was going to do? Was that what she had been struggling to tell me before I hurried to end our session?

“I’m not trying to kill myself.” Though his expression was flat, Nigel McGowan’s color—at least how it appeared on my laptop screen—was whiter than the wall behind him.

How many times have I heard those words? Another patient had sworn the same to me only two days before, during my week- end on call for the Anchorage Regional Hospital. That patient had begged me to free him from his involuntary confinement in the ER. But the raw ligature burns around his neck—from where the noose had yanked the hook free from the ceiling at the last moment—were far more persuasive than any of his pleas.

“You’re not suicidal,” I said, focusing back on Nigel. “You just don’t want to extend your life any longer than necessary. That right?” “Exactly right, Dr. Spears,” he said, as sweat beaded along his receding hairline.

Having seen the worrisome images of Nigel’s swollen, red-and- black blistered foot and shin, I was surprised he was upright at all with such an overwhelming infection snaking up his leg and into his bloodstream. “All right, Nigel,” I said. “Say I dove to the bottom of a swimming pool and decided not to extend my life by resurfacing. Wouldn’t that make me suicidal?”

He crossed his arms and rested them on his bulging belly. “That’s a silly comparison.”

“Is it, though? You’ve had uncontrolled diabetes for years, and you still refuse to take insulin. It gave you a heart attack before your fortieth birthday. And now you’ve got an infection that, according to your own doctor, will cost you your leg—probably your life—unless you agree to go to hospital for intravenous antibiotics.” I pointed at the screen. “Make no mistake, Nigel. You’re killing yourself. You’re just doing it slower than most.”

*****

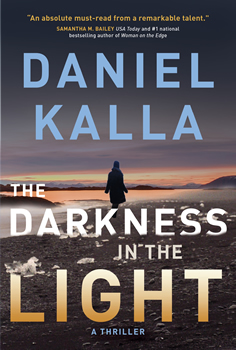

Born, raised, and still residing in Vancouver, Daniel Kalla spends his days (and sometimes nights) working as an Emergency Department in a downtown Vancouver teaching hospital. Daniel is also the author of twelve published novels, which have been translated into thirteen languages. He has had had multiple novels optioned for film, and his Shanghai trilogy is being developed for a TV series.

His latest novel, THE DARKNESS IN THE LIGHT (Simon and Schuster, May 2022), is a Scandinavian-noir style thriller set in the 2nd northernmost community in the world. In it, a psychiatrist and social worker team up to investigate an epidemic of what appears to be suicide in Utqiagvik, Alaska. But instead, they find themselves thrown into a terrifying journey of treachery and death—one that will horrify this isolated community and endanger more lives.

Daniel received his B.Sc. in mathematics and his MD from the University of British Columbia, where he is now a clinical associate professor and the department head of a major urban ER. He the proud father of two girls and a poorly behaved but lovable mutt, Milo.