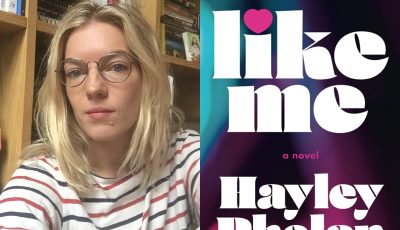

Up Close: Hayley Phelan

Dying to Fit In

By Dawn Ius

By Dawn Ius

Hayley Phelan has written a lot about the impacts of media on youth. As a journalist for magazines like Teen Vogue, Elle, and Vanity Fair, she’s delved into the dangers of the influencer culture, explored the addictive nature of social platforms like Instagram, and even researched the tragedy of Britney Spears’ conservatorship.

But with her debut novel, LIKE ME, Phelan cranks things up a notch to deliver a propulsive debut she hopes will not only entertain, but also encourage youth to take a hard look at the impact of social media on their lives—and ultimately, determine whether those “likes” are worth it.

LIKE ME is a “psychological thriller that follows an aspiring model down a social media-fueled rabbit hole of obsession, narcissism, and self-destruction.” It will also leave you wondering whether you’re refreshing that Instagram feed a little too often.

For 19-year-old Mickey, the aspiring model in Phelan’s novel, it’s not a question—it’s a given. For her, Instagram is a portal to the world she wants. More specifically, it’s a way for her to track the day-to-day movements of her idol, model Gemma Anton.

Mickey has studied everything about Gemma’s famous world—so much so that when a chance meeting hands her the opportunity of a lifetime, Mickey thinks she’s got it all under control. She doesn’t, of course, and as she rides that wave of instant success, the lines between fact and fiction become increasingly blurred—and ultimately more dangerous.

In this interview with The Big Thrill, Phelan talks more about the inspiration for her timely debut, what she hopes readers take away from the story, and why it was important for her to explore some of the novel’s deeper themes.

Reading your bio, it’s clear where the inspiration for LIKE ME could come from—you’re immersed in the youth culture world and have written many articles about how media impacts young women. LIKE ME, however, takes that impact to the next level. Was there an incident in particular, or something you learned, that sparked this thriller?

Working in fashion, I met many young women whose self-worth depended on how well they fit into a certain beauty ideal…it wasn’t some hidden struggle either; rather, it was very much a sanctioned part of their job and career. It wasn’t limited to models either, though certainly being on set with teenage models, some of whom were barely 16, informed part of the novel. As Instagram and social media became more important, Likes and metrics started to rival weight and wardrobe, and I witnessed many an adult woman do all sorts of embarrassing things just to get a good Gram. What interests me though is that if we’re honest, many of us can relate to these desires and the pressure to get the perfect shot—no matter what industry we work in. It’s not our personal failing—it’s the way these social media applications have been designed—to be highly addictive and often socially corrosive.

As an accomplished journalist, you’ve written for so many incredible publications. But writing fiction is, of course, a different skill set than writing nonfiction. What aspects of writing nonfiction have helped you transition to fiction? And which have been more of an obstacle?

I always wanted to be a fiction writer, but when I got out of college, I couldn’t exactly get a job writing novels. Instead, I pursued magazine work and wound up getting hired at Teen Vogue, which began my career in journalism. Working at magazines and websites taught me to write quickly, cleanly, and to get to the point. My editor and friend Leah Chernikoff would always quiz me after I turned in a piece—”Would you keep reading after that first sentence?” Clarity and concision are everything—a trap I think some beginning fiction writers, including myself, can fall into is thinking more words equals more. And of course, perhaps most importantly, journalism taught me how to meet deadlines and work under pressure. Being a journalist however, I can get caught up in details and mechanics, which can weigh down the scene—I received many a revision with entire paragraphs cut. Here again, though, my experience in journalism came in handy—I’m so used to the editing process that I don’t flinch over a big red X. I’m usually excited that someone has seen a way to trim.

I don’t think anyone could have predicted how addictive—and dangerous—social media would become. As old technologies platforms fade out, new ones emerge, each more immersive and invasive than the last. What do you hope readers will take away from this story, aside from a propulsive read?

Phelan celebrates the completion of her MFA at the Hemingway bar at the Ritz. “I wrote most of the novel in the program under the incredible mentor ship of Helen Schulman and Katie Kitamura and many others,” Phelan says.

I hope readers take a second to reflect on how social media may be impacting their psyche or self-worth and wonder if it is really worth it. Social media companies like Facebook (ahem, Meta?) have been really good at convincing us that their technologies are neutral; this puts the onus on the individual…people are ashamed to admit how much social media may be impacting their psyche or behavior, as if that were indicative of a personal flaw, rather than a function of design. Saying you can use social media without getting addicted is like saying you can smoke cigarettes without getting addicted…sure, but only up to a point. I think because social media use and addiction has been associated with young women, it hasn’t gotten the serious attention it deserves as to how it is shaping our culture and our psyche.

One of the things that makes this book so engaging and clever is your protagonist, Mickey Jones. I’d love to hear a bit about how she developed for you—was she based on people you’d interviewed or met? Someone you know?

I’m sure all writers are magpies, picking up little tidbits here and there—overheard conversations in the women’s restroom, a certain friend’s personality quirk, or an interview from a magazine—except instead of weaving together a pretty nest, we make tangled-up characters. I’ve always been drawn to characters that are contradictory and difficult in some way—I don’t care if a narrator or protagonist is moral or “likeable,” only if she or he is interesting. Mickey reminds me of a lot of people I’ve met and know; she also reminds me a bit of myself in high school, when I used to pore over magazines and cut out images of women I’d like to be one day. When I look at my diary from that period, I find it as heartbreaking as it is embarrassing.

I read part of a review that said, “Don’t confuse Mickey with Michaela,” and I love that, because it speaks to how you essentially had to create two characters for your protagonist. Was one side of her easier to write than the other?

What’s so cool about writing a novel and sharing it with the world is that wonderfully smart readers will notice things you weren’t aware of, making you seem a lot cleverer than you are. I didn’t conceive of Mickey this way consciously, though I did have a clear idea of a shift in her character pre, during, and post the bulk of the narrative.

I think sometimes people dismiss influencer culture as being a bit fluffy, but LIKE ME explores some of the darker themes that lurk behind what it takes to get that perfect Insta-shot—you don’t shy from tough topics like racism, sexual abuse, mental health. Tell me more about why you wanted to make sure those themes found a home in the book?

First of all, the influencer culture that Mickey is a part of, or trying to be a part of, is very much a white privileged space, and I thought that was an important aspect to acknowledge and explore. Mickey is trapped in this white privileged paradigm even as she is benefitting from and reinforcing it. Here, I was thinking of someone like Britney Spears, whose struggle I wrote about for Vanity Fair early on in the Free Britney movement. When I initially began reporting that story, I thought it was interesting and perhaps misguided that a group of people were rallying around the freedom of this inarguably very rich, blond woman while the BLM rallies were unfolding at the same time. I think a lot of people thought the Free Britney movement was a bit of a joke at first—much the way, unfortunately, people reacted to her mental health struggles in 2007. But the deeper I got into the reporting, the more I felt like the conservatorship really was unjust.

Secondly, while it’s true that social media has brought more light to issues of mental health, sexual abuse, and racism, particularly the kind of casual racism that doesn’t make headlines (thinking of all the Karen behaviors caught on tape), I was interested in the way those calls to action often lived alongside vacation photos, thirst traps, or artfully-arranged tableaus of three-thousand-dollar bags. It’s been quoted and misquoted to death, but McLuhan’s “medium is the message” is relevant; we need to think about how it is changing the way we make meaning of these images, that we encounter them all on the same platform, in quick succession. I think the line between performance and natural expression can get blurry. There is a long tradition of women performing their trauma—in late 19th century France, the hottest ticket in town was to sit in on the Salpetiere Asylum and watch women be treated for “hysteria”—and while I absolutely commend the very brave people who have shared their stories online, the way that those stories are engaged with, almost as if they were entertainment, needs further consideration.

“I moved to Los Angeles halfway through working on the novel,” Phelan says. “I’d go for walks outside and collect the flowers that had fallen to the ground as a palette cleanser after particularly icky scene writing.”

At times, I almost felt uncomfortable reading the book—but in the very best way. Intentional?

Thank you! I believe that the best work can make one uncomfortable, so I take this as a huge compliment!

I imagine your nonfiction work provided more than enough background for this book, but in the event that you had to do more research, was there anything you learned that surprised you?

Some of my “research” entailed trolling Instagram and reading interviews or long-ago posts from social media influencers. I was sometimes surprised to find that their actual quotes were even more ridiculous, tone-deaf, or alarming than I would have been able to dream up. It didn’t surprise me, but may surprise readers, to know that often after just a few days of having Instagram back on my phone, my “research” started to meander further and further, and I found myself checking the app first thing in the morning, buying things I didn’t need and getting sucked into the popular page.

What can you share about your current WIP?

I’m working on a novel centered around a complicated father-daughter relationship; the stories that are told from one generation to the next and the stories that never get told—but are inherited nonetheless.

- On the Cover: Alisa Lynn Valdés - March 31, 2023

- On the Cover: Melissa Cassera - March 31, 2023

- Behind the Scenes: From Book to Netflix - March 31, 2023