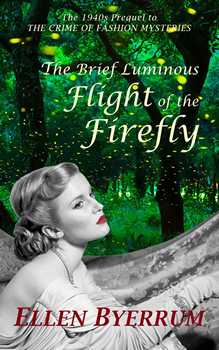

The Brief Luminous Flight of the Firefly by Ellen Byerrum

It’s June 1943, halfway through a world war that has ramped up patriotism, but has also resulted in hoarding, profiteering, theft…and murder.

A young Mimi Smith has gone to Washington to work for the war effort, but she’s not content to be a mere stenographer at the government agency that investigates black market activity. Her curiosity and passion send her down a dangerous path in which she discovers a connection to a killer no one else seems to suspect. Soon, she teams up with a skeptical policeman and a country boy to trap a killer—but can they do it in time?

THE BRIEF LUMINOUS FLIGHT OF THE FIREFLY is the prequel to Ellen Byerrum’s bestselling Crime of Fashion Mysteries featuring Lacey Smithsonian. In this interview with The Big Thrill, Byerrum shares insight into her background, her characters, and where the series will lead readers next.

You have worked as a reporter, a playwright, a media professional, and a mystery writer. Which is easiest and what specific skills are needed for each job?

Nothing is easy, though I wish it was. However, I’ve loved each job for various reasons at different times. I toiled at an advertising department for a major hair salon company on the East Coast for a short while and got an idea for my first mystery, so it wasn’t a loss.

A reporter must be able to take facts, quotes, and background and combine them succinctly into a story in a short period of time. You learn to write on deadline and to be a professional, and hopefully an objective, observer. You’re always listening for the great quote to add flavor to your stories. You’re learning about voice at the same time. For example, I once had to ask a company about Occupational Safety and Health Act citations it had received for an employee’s amputation. “Amputation?!” The woman I had reached for comment was indignant. “They didn’t cut it all off! They sewed it back on!” (It was a hand.)

I could never use that quote in our publication, but obviously I filed it away for later use.

Playwriting relies on story, memorable characters, dialogue that gives voice to characters, and fun things like planting plot points that pay off later. To loosely paraphrase Chekhov’s useful rule, if a gun is brought on stage in the first act, it had better go off by the third. A playwright should learn about and implement story arcs and character arcs and be good with rising action and climaxes.

In my opinion, reporting and playwriting were the best possible preparation for writing mysteries and thrillers. It all works together to create books with a distinctive voice. There is one more skill I think you need, and that is the skill of letting go—letting go of doubts and preconceptions and all the negative voices that say you can’t do it. Just go for it.

What’s the oddest thing you’ve turned up during your research for your books?

Believe it or not, nylon stockings were wildly popular after being introduced by DuPont in 1939. Then during World War II, the government said no more nylon stockings would be manufactured; all the nylon was needed for the war effort. That news sparked riots in department stores all over the country. But that news was actually a lie: one US plant continued to secretly make stockings for the government, for the express purpose of paying foreign spies. Nylons were that popular, and they were also portable, practically weightless, and could be hidden inside linings of clothes.

I was also stunned to find out that, according to numerous online sources, Britain bought up (or tried to buy) the world’s entire supply of tea at the start of WWII. (I’m still skeptical about that.)

I’ve also learned:

- The various ways to die in a velvet factory, including being slashed by six-foot-tall blades.

- Bodies in the St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 in New Orleans must lie in the above-ground tombs for at least a year and a day. (They are naturally cremated in that time and then the ashes can be moved and mixed with other ashes in the mausoleums.)

- Some theatrical costumers believe that spilling a drop of blood into a costume (for instance, by pricking a finger with a sewing needle) is good luck and means a “good show.” “Bloody thread, knock ’em dead.”

- Paris Green is a toxic dye made of copper acetoarsenite, which when activated by moisture, such as humidity or sweat, is highly toxic, and releases arsine gas. It may have had a hand in Napoleon’s death. Also, it creates beautiful shades of blue and green.

- While buildings and locations can be haunted, clothing rarely seems to be inhabited by spirits.

You do a fair number of author panels. Have you ever been stumped by a question from the audience?

I’m usually stumped when people ask about my favorite books and authors and what’s influenced my writing, because I’ve been so focused on the topic I tend to draw a blank. Now I try to write up a few ideas beforehand.

Very wise. My “spontaneous” answers are usually well-planned. What was the most interesting panel you’ve ever done?

They’re all great in their way; however, one stands out because of the company in which I was grouped. I was thrilled to be on a panel with the incredibly talented authors Anne Cleeves, Dana Cameron, Louise Penny, and Nancy Pickard, talking about the experience of having our books filmed.

My favourite panel was “lost” detectives, in which I championed Henry Bohun. Have you a recommendation for readers of a detective who seems to have slipped out of view?

Thanks for the heads up on Henry Bohun. I’m sad to say I hadn’t heard of him. However, I loved Paris Chandler, who appeared in only two books by Diane K. Shah, As Crime Goes By and Dying Cheek to Cheek. Paris Chandler is a gossip reporter in the late ’40s and early ’50s in Los Angeles. The books are so well observed and dishy, and I’ve read them numerous times.

THE BRIEF LUMINOUS FLIGHT OF THE FIREFLY is set in 1943—an era which is both strange and familiar (given all those wartime films and series). How did you ensure you captured the flavor of the times (which you do) without resorting to cliché?

When you write about specific characters and not stereotypes, they take the lead—the way they act, the way they speak, and the way they look. The ’40s were not that long ago, people are still people, and the human reactions we have are still the same.

In the book, I’ve tried to create a story that hadn’t necessarily been told before, at least not in the way I wrote mine. Mimi Smith is mentioned in many of the Crime of Fashion Mysteries, and I inadvertently gave myself a problem by having her work at the Office of Price Administration. It wasn’t a glamorous agency, it was greatly disliked and disparaged, and it was disbanded shortly after the war. I researched OPA documents from the National Archives and papers and photos in the Alexandria Library Barrett Branch Local History/Special Collections. I read a variety of American magazines from 1943 (and other years), including Esquire, Life, Mademoiselle, Vogue, and Glamour, which all capture the lingo of the times. I also interviewed women who were alive during the war, including a neighbor who joined the Marines (inspired by their recruiting slogan for women, “Free a Marine to fight!”) and needed her parents’ permission because she was only 20. Their stories all informed my work, as well as my imagination.

Finally, there are some parallels to our lives today, living through the pandemic. During the ’40s, there were shortages of goods, travel was restricted, and loved ones were dying in a global crisis. Nothing is new.

Agreed! In the book, Mimi says it’s pretty easy to get the wrong impression from someone’s clothes. Are those your words being put in your character’s mouth?

If you think about it, all the words in all the characters’ mouths are mine. However, I do believe that our clothes tell stories about ourselves. Our clothes can tell the truth and they can tell lies. They can say true things we don’t realize they’re saying, and they also tell lies to conform to someone else’s rules, like uniforms do. Clothing can be a whole nonverbal language. That’s why clothes are so much fun to deal with in fiction.

Is Mimi based on a real person? If not, where did the inspiration for her come from?

Like so many characters, Mimi arrived in my mind one day with many strong opinions. Although there were women in my family who lived during the war, and I have interviewed women of that period, Mimi was not based on anyone in particular. My Great-aunt Ruth was just one woman who always worked, including during the war, at a time when many women found amazing new opportunities. After the war ended and the servicemen came home, Ruth was not happy that she had to train a man to do her job, the man who would become her boss. Women were happy of course to have their men come home, but many found it infuriating to be pushed “back into the kitchen.” Ruth was a passionate believer in equal rights and women’s rights. Who knows what I may have absorbed?

*****

Mystery and thriller writer Ellen Byerrum is a former journalist in Washington, DC, as well as a produced and published playwright. For research, she received her private investigator’s registration for Virginia.

Her latest book, the BRIEF LUMINOUS FLIGHT OF THE FIREFLY, is the 1940s prequel to her Crime of Fashion Mysteries and features a very young Mimi Smith, the “Great-aunt Mimi” mentioned throughout the series. FIREFLY takes place during WWII in Washington, DC.

Stretching beyond the mystery form, Byerrum has written a stand-alone psychological thriller, The Woman in the Dollhouse, which Best Thrillers says “bewitches on page one and continues to mesmerize until its shocking conclusion.” Two of her plays under the pen name “Eliot Byerrum” have been published by Samuel French, Inc. and are available through Concord Theatricals.

To learn more about the author and her work, please visit her website.

- The Deception by Kim Taylor Blakemore - September 30, 2022

- Death In The Aegean by M.A. Monnin - May 31, 2022

- Bad Blood Sisters by Saralyn Richard - February 28, 2022