Celebrating Two “Darkly Ingenious” Releases

It’s been more than 22 years since John Connolly roared onto the thriller scene in May 1999 with his brutal debut Every Dead Thing, featuring cop-turned-PI Charlie Parker. Reviews were deservedly enthusiastic, with Publishers Weekly calling the book “darkly ingenious” and Kirkus hailing Connolly as “extravagantly gifted.” Those reviewers knew a good thing when they saw it. Connolly has gone on to become one of the most prolific and popular authors in the realm of crime fiction.

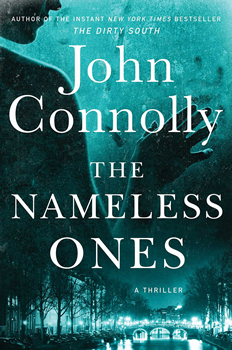

Now that Connolly is 19 books into his series (or 20, if you count Parker’s blink-and-you-miss-it appearance in 2003’s Bad Men), Parker’s world has expanded and branched off in unexpected ways. Connolly has turned his tortured detective into the hero of a sprawling supernatural epic populated by some of the most memorable characters in modern fiction. Among them are Parker’s steadfast friends Louis and Angel, who step into the spotlight for the latest series installment, THE NAMELESS ONES.

For the uninitiated, Louis and Angel are career criminals (a hitman and a burglar, respectively) who traffic in vigilante justice and serve as Parker’s trusted confidantes, extra firepower, and surrogate family. Partners in crime and in life, the couple defy stereotypes at every turn. There are regrettably few gay men in crime fiction, but there are none like Louis and Angel.

Photo credit: Mark Condren

Connolly’s latest thriller finds the pair traveling to Europe to avenge the breathtakingly savage torture and murder of Louis’s friend, a Dutch fixer named De Jaager, and three members of his household. The killers are Serbian war criminals, and the murders are the latest in a cycle of violence rooted in the Serbo-Croatian wars that followed the disintegration of Yugoslavia after the death of its president, Josip Broz Tito, in 1980. The action takes Louis and Angel to Amsterdam, Austria, and South Africa, while Parker remains stateside (though he’s still caught up in the mission’s fallout).

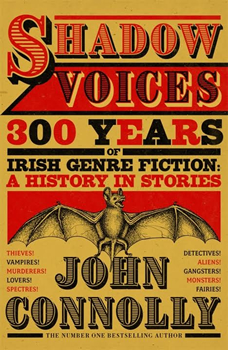

Despite its globetrotting scope, though, THE NAMELESS ONES isn’t the most ambitious book Connolly released in October. Two days after THE NAMELESS ONES went on sale in the US and Canada, readers in Ireland and the UK got a crack at SHADOW VOICES, Connolly’s massive survey of three centuries of Irish genre fiction. Besides collecting horror, crime, science fiction, and romance stories culled from 300 years of Irish literature, the 1,100-page book features lengthy essays, introductions, and in-depth notes by Connolly.

In his latest interview with The Big Thrill, Connolly answers questions about both of his new releases and teases future projects, only some of which will involve Parker.

THE NAMELESS ONES feels like a departure for the series in terms of geographic scope—the story starts in New York, but soon Louis and Angel are traveling all over Europe. What inspired that choice?

It was something of a reaction to The Dirty South, most of the action of which took place in one very small county in Arkansas. After a book like that, the natural response was to write a novel that ranged as far and wide as possible. Also, I very much wanted to write a globetrotting thriller, which is a form of fiction that I’ve always loved, with a smattering of the espionage genre thrown in for good measure. Mind you, I’m glad that I got the on-the-ground research done before COVID-19 hit, or else I’d have had to come up with another book entirely and put that one on the back burner.

Can you trace THE NAMELESS ONES to a specific inspiration?

Not so much the genesis of the book, but it came together during a trip to Vienna, which was a city I knew I wanted to use in the book, as much for the atmosphere as anything else. A writer named Robert Pimm suggested I visit the Cemetery of the Nameless, which is where bodies washed up by the Danube would be buried, many of them anonymously. That gave me a title, a central metaphor, and a crucial scene in the book. After that, I was sailing.

In your author’s note at the beginning, you mention talking to a Serbian man about the Serbo-Croatian wars. What kind of research did it take to write THE NAMELESS ONES?

I’d visited Croatia in the past, and read a certain amount of fiction and nonfiction that had come out of the Balkan conflicts, but I was no expert. I had to immerse myself in a lot more reading, followed by some time spent in Serbia. I can’t write about a place I haven’t been. That’s never changed.

What’s the most surprising thing you learned during that research?

That if you visit the Military Museum in Belgrade, there’s no mention of the Balkan conflicts at the end of the last century. It pretty much goes from the death of Tito to Serbia’s involvement in UN missions this century. There’s a kind of denial about what happened in the interim.

Do you find it creatively helpful to write books in the Charlie Parker universe that don’t necessarily feature Charlie in a prominent role?

I find it helpful to write books that aren’t Parker novels, or mysteries. It would have been difficult for me to develop (and, I hope, improve) as a writer by writing only Parker books. Instead, I tend to step back from the books every year or two in order to exercise a different muscle, and perhaps work on some new skills, which I can then apply to the Parker novels.

As you get further and further into the series, does it seem to get harder, or easier?

I think there’s a certain comfort and familiarity with the characters, which helps. On the other hand, I’m very anxious not to repeat myself, so I try to do something different with each book. That’s the hard part.

You’ve been writing this series for more than 20 years. Knowing what you know now, is there anything you’d do differently in the early Charlie Parker books?

Gosh, that way lies madness. There are some elements of the early novels that are perhaps too conventional, but then I was in thrall to the genre to some degree. I’d like to think that the stranger, less familiar elements to the books balanced out the more typical, but I may not be the best judge of that.

Besides THE NAMELESS ONES, SHADOW VOICES also came out in October, and you always seem to be juggling at least 38 projects at once (and I think that’s a conservative estimate). What’s your secret to time management?

It’s pretty simple, really. I work quite slowly, but I work slowly almost every day, and once I start something, I finish it. I’m also very bad at taking time off, which probably helps…

In SHADOW VOICES, you make a point of highlighting how important genre fiction has been to women, both as readers and writers. Can you talk a bit about that connection?

Well, fiction has generally been driven by women as consumers. The earliest reading societies, 19th-century forerunners of our modern book clubs, divided very much along gender lines, with women preferring fiction and men opting for nonfiction. That’s a pattern that continues to this day, with women, according to some studies, consuming as much as 80 percent of modern fiction.

But women were also very attuned as creators to the possibilities of fiction. Again in the 19th century, women at one point accounted for as much as 50 percent of the fiction being produced. (In the UK, it’s now more than 60 percent.) I think there was certainly an economic impetus for their embrace of genre fiction quite early on. Until the end of the 19th century, women in Britain had no financial or property rights—and that included intellectual property, so female writers had to have male relatives, or their husbands, negotiate their contracts and look after their income. When they were finally granted control over this aspect of their lives, it perhaps wasn’t surprising that women authors would write what sold, because that kind of financial independence was so new.

But women were also very attuned as creators to the possibilities of fiction. Again in the 19th century, women at one point accounted for as much as 50 percent of the fiction being produced. (In the UK, it’s now more than 60 percent.) I think there was certainly an economic impetus for their embrace of genre fiction quite early on. Until the end of the 19th century, women in Britain had no financial or property rights—and that included intellectual property, so female writers had to have male relatives, or their husbands, negotiate their contracts and look after their income. When they were finally granted control over this aspect of their lives, it perhaps wasn’t surprising that women authors would write what sold, because that kind of financial independence was so new.

But they use it in interesting ways: romantic fiction, for example, so often belittled by male critics and readers, even now, was a way of interrogating issues of property, wealth, and matrimony. The Irish writer Charlotte Riddell wrote all kinds of fiction, but her ghost stories are particularly striking because they’re haunted as much by fears about money as fear of ghosts. SHADOW VOICES features “Madame Sara,” a detective story by the Victorian writer L.T. Meade—pioneer of the medical mystery and the girls’-school novel—which plays on fears of the New Woman: financially independent, and the owner of her own business. The story is based on a real case, that of a woman named Madame Rachel, and it’s fascinating to see Meade use it. These are stories, I would argue, that wouldn’t, and couldn’t, have been written by men.

SHADOW VOICES sounds like a massive undertaking. How long did you work on it, and how did you decide what to include?

It’s been gestating for a long time, but I began work on it shortly before COVID hit, in part out of frustration at how regressive attitudes to genre writing continued to be in Ireland. But rather than just assemble a collection of genre stories and use them to make the argument for its importance, I wanted to put together something more ambitious. Because Irish writers have been influential in genre writing in a way out of all proportion to our population, it became a way to look at the history of genre fiction in general, and how some of the misconceptions about it came into being. The book is almost 450,000 words long, but about a quarter of that is original content: essays, a general introduction, notes… And so many of these writers led curious, sometimes tragic lives, so the stories in the book are as much the stories of their lives as the ones they created.

Have Irish critics been even more dismissive of genre fiction than their counterparts in other countries? If so, why do you think that is?

On one level, it’s historical. Even towards the end of the 19th century, influential figures—including the country’s future first president Douglas Hyde—were suspicious of genre writing, with Hyde enjoining people to turn their backs on “penny dreadfuls, shilling shockers.” In part it was because they were perceived as very English forms of writing, and the movement towards independence involved trying to re-engage with more Irish forms of literature: cultural revolution before armed rebellion, if you like. That continued after independence was achieved in 1922: to be an Irish writer meant to be engaged with Irishness, and genre fiction had no part to play in that, a belief that has persisted in some circles until quite recently. And Irish writing in the 20th century is very male-dominated, so women get excised from the canon—which means genre gets excised too, although that’s true in general of much of the first half of the 20th century: modernism is very masculine. It’s striking that by the 1950s, female representation among writers of fiction in Britain had fallen to just 25 percent, historically its lowest point. So Irish genre fiction suffers due to circumstances both specifically Irish and more general: that’s why the damage is so great.

Can you say anything about what’s next for you?

Well, the next Parker book has been delivered, and I’m working on the Parker for 2023. There may also be another installment in the Nocturnes [short fiction] collections, and perhaps something non-Parker after that—if the Lord spares me, as we Irish like to say, just to be on the safe side.

__

Ed. note: THE NAMELESS ONES is available now from most US booksellers. SHADOW VOICES is currently on sale in Ireland and the UK; watch Connolly’s website and Twitter feed for an announcement about upcoming US availability.