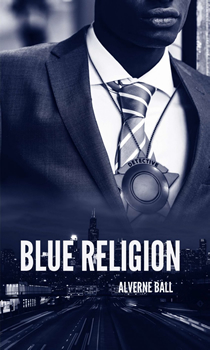

On the Cover: Alverne Ball

A Different Kind of Police Procedural

Since completing his MFA in Fiction Writing at Columbia College Chicago, Alverne Ball has published acclaimed graphic novels, written for television shows in South Africa, created online comics series, written and produced a short film, and racked up an impressive array of awards and fellowships.

Most recently, Ball has turned his attention to a series of police procedurals featuring Chicago minister-turned-homicide detective Frank Calhoun. In the noir-tinged 2016 series launch Only the Holy Remain, Calhoun investigated the murder of a local priest. In this month’s follow-up, BLUE RELIGION, Calhoun must root out the killer of a social worker and a rookie cop who are gunned down in Chicago’s East Garfield Park neighborhood.

Ball recently joined The Big Thrill for a talk about why he chose such an unusual career progression for his detective, crime fiction’s role in America’s reckoning with police violence, and expanding the horizons of the publishing industry.

You’re obviously a big fan of crime fiction. When did your love of the genre begin?

I think it started with my first reading of Hardy Boys: Dungeon of Doom. That book combined what I loved about Dungeons and Dragons (the cartoon series) along with what I’ve always liked about mysteries, the whole whodunit or how it was done. It’s always the motive for me that gets me intrigued about a good mystery.

Of the many mystery/thriller/crime fiction subgenres, what drew you to police procedurals?

I think what grabbed me and pulled me into police procedurals was this duality that I think police officers face: being the protector of society while trying not to lose their humanity in the service of the people. That constant battle with oneself/the demons that the job can conjure up has always been something that has intrigued me about officers of the law. Also, the procedural part is a basic “how to,” and the more you look into how something is done, the more you find the cracks in the system and how those cracks create crevices that can engulf individuals or whole communities, and all because someone created the process for how something is done.

Your background is in graphic novels and screenwriting, two disciplines that rely heavily on images. How did working in those mediums help you as a novelist, and what was the biggest challenge when you started the Frank Calhoun books?

Funny part is that it was writing prose that actually helped my work when it came to graphic novels and screenwriting. See, I come from the Columbia College Chicago creative writing thought process of “seeing in the mind,” which means to see a scene with characters play out in front of you as if it might be a play or, say, a movie. This interaction with story actually helped me visualize scenes more easily when writing comics and graphic novels because I could see, smell, hear, and taste everything in a scene, so when I’d write scripts for comics, it helped me get those visualizations across to the artist with as much compact description as possible. Learning to write comics then in turn taught me how to be a screenwriter because the two mediums are very similar. I learned to write screenplays by reading them and then taking what I do in comics and again, learning to write more compact and exciting prose without forcing myself to write, say, a book-length paragraph.

The biggest challenge I encountered with writing the Frank Calhoun books was thinking about how this character would evolve and how that would look on the page. I was just discussing the first book (Only the Holy Remain) with a friend of mine who had recently read the book, and I revealed to her that there are a number of bread crumbs in the first book that propel the third and fourth books in the series to a place that, when I first started writing about Frank, I didn’t know, because that first book was initially a short story that took on a life of its own and became a novel.

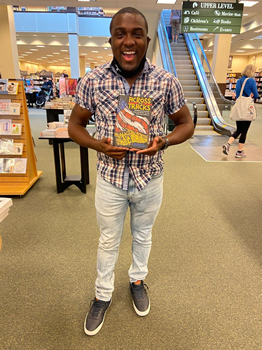

Ball discovers his graphic novel Across the Tracks: Remembering Greenwood, Black Wall Street, and the Tulsa Race Massacre, on the shelves of Barnes & Noble.

Tell us a little about writing Frank Calhoun and how the character took shape for you.

For me, Frank became an embodiment of what I wasn’t seeing in crime fiction, which were characters that looked like me, that sounded like me, but more importantly, I wanted Frank to represent Chicago in a way that most people will never know because of how the media either vilifies the west side of the city or ignores it all together. Frank “Preacher” Calhoun was once an ordained minister, now turned homicide detective. I chose that as his profession because I wanted there to always be this fight for the greater good of his soul versus the greater good of his humanity.

When you wrote the first Frank Calhoun novel, Only the Holy Remain, did you know there’d be a sequel?

I actually didn’t. As I stated previously, I wrote Only the Holy Remain as a short story, but then one of my good friends asked what happens next, and so the novel was born. By the time I finished the first novel, I had this other novel in my head, which I had started writing before Only the Holy Remain, entitled Sins of the Father. I didn’t know that it would be the third novel in the series; that occurred when I thought about this crime that had happened some 12 years prior in Chicago and how the city had crucified this young Black man who from day one had pleaded his innocence but was altogether ignored by the media, the arresting officers, and most of the city, except for his public defender. For this reason, that I now see as being blatantly wrong because of the system of law and those that fall into those cracks, that story stayed with me until it became BLUE RELIGION.

Can you tell us a little about your writing process?

I write mostly everything longhand, except for screenplays. I’m old-fashioned because all I need is a pen and pad and I find myself lost in the story. I wrote my first novel while commuting on the train in the morning and then at night I’d sit inside a loud bar and continue to write while drinking a Sprite or root beer. I tend to write a good number of chapters longhand and then at some point I’ll start to type up those chapters, but in order to stay ahead of myself, I’ll usually write two or three chapters for every chapter that I type.

As America continues its long-overdue reckoning with police violence, what role can crime fiction play in that conversation?

I think crime fiction is a reflection of our society, and when we (crime authors or screenwriters) continue to paint these men and woman as being saints instead of flawed human beings, we are doing society a disservice. I included screenwriters because when one watches any police procedural show, you’ll have a good cop/bad cop scenario, and the fact that the bad cop can play Batman because the end justifies the means results in us losing sight of what that human being is supposed to be doing by way of the laws that society has deemed reasonable. At the same time, we can’t overlook or bypass the racist or racially biased laws that were put in place to assist the officers of the law with breaking or manhandling said law.

As crime fiction authors, it’s our duty to not only paint a true picture of our society but to also try and right the wrongs of said society when we see it. I once read this Chicago author who had his White protagonist go into the Cabrini Green housing projects, and he comes across a Black gangbanger, and the Black character says the “N” word but phonetically speaking and as I read that I realized that this author didn’t know the culture of the people he was writing about because if did he would have realized that the Black character would have never said such a word to a White character, especially in such a brief meeting, as the two were like two ships passing in the night. I bring this up because this writer portrayed Cabrini Green and its high-rises and this banger as the scum of the Earth, but if you look at Cabrini Green now, it’s a gentrified poster child for the ideal Chicago utopia. Now, any writer that had done just a little research could have painted a different picture, one where there is humanity even in the starkness of this environment because the realization that poverty and the lack of resources is but an end result of what created the apocalyptic Cabrini Green and the banger, instead of possibly showcasing the working-class family that also resides there.

If you could change any one thing about the publishing industry today, what would it be?

The lack of POC at the top of the pecking order. A great deal of publishing is controlled by a White vision of what the world should be, see, and feel. That vision is also shared by a number of “agents” who help corral and keep the status quo of the gatekeepers in their comfort zone. I say a change at the top because this is where the vision of what can be marketed and sold comes from, but when there is a diverse understanding of a wider world and the different backgrounds of people and their stories flow out of the cracked melting pot of humanity, then we find ourselves not limiting what people can see or read, but in fact we expand their horizons to reach and find a new level of curiosity beyond their own knowing of how and what a story should be.

At the end of BLUE RELIGION, Frank is in a very different place. No spoilers, of course, but do you plan to continue his story?

Yes, and I’m very interested to see how he handles this new place going forward in his life as he grapples with being a man without a country in a country that demonizes him for his existence.

Can you tell us anything about what’s next for you?

I have a crime comic coming out this October from Sacramentum Press entitled Crook County. And then in 2022, Sacramentum will be publishing my illustrated fantasy-crime novella entitled The Butcher of Idawe, the first book in the Apothecary Mystery series. I recently adapted Shakespeare’s Othello into a graphic novel set in modern-day Iraq, which I’m looking to shop to publishers. Lastly, I have a crime drama series, entitled Roman starring Chicago native Simeon Henderson as the title character that will be premiering on a streaming network in 2022.

- Africa Scene: Iris Mwanza by Michael Sears - December 16, 2024

- Late Checkout by Alan Orloff (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024

- Jack Stewart with Millie Naylor Hast (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024