Fact and Fiction Intertwine in Stunning Debut

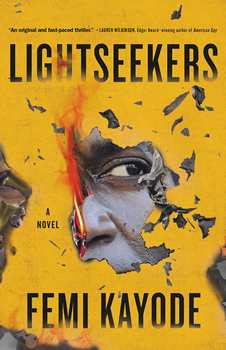

Nigeria has produced some excellent new mystery and thriller writers in recent years, and Femi Kayode is no exception. His debut novel, LIGHTSEEKERS, could be described as a psychological thriller, but it’s completely different from the type of book that comes to mind in that sort of pigeonhole. This is a special book, and reviewers agree. It was selected as a Best Crime Novel of the Month by The Times, Sunday Times, Independent, Guardian, Observer, Financial Times, and Irish Times. Few debut authors get that sort of recognition.

Femi Kayode trained as a clinical psychologist in Nigeria before starting a career in advertising. He has created and written several prime-time TV shows. He recently graduated with distinction from the UEA Creative Writing program and is currently a PhD candidate at Bath Spa University. Kayode won the UEA/Little, Brown Award for LIGHTSEEKERS when he was still writing the novel. He lives in Windhoek, Namibia, with his wife and two sons.

In this interview for The Big Thrill, Kayode shares more about his startling debut, and how fact and fiction sometimes intertwine.

Would you tell us a bit about yourself and what brought you to write LIGHTSEEKERS?

It’s really hard to cram 50 years into “a bit,” but I’ll try. I grew up in Lagos, Nigeria, and hold a postgraduate degree in clinical psychology. I have worked in advertising since I decided not to practice psychology. I’ve written several stage plays and worked in film and radio. I live in Namibia with my family. Sometime in my mid-forties, I think I had a midlife crisis. I suddenly looked at my life and felt I had not done anything of meaning or impact. It’s like that movie, It’s a Wonderful Life, except this time there was no angel coming to show me all these great and amazing things I had done. While I was proud of my professional life in advertising, I still felt this need to have something of mine that I could be proud of, that hopefully lives long after me. I went back to school at the University of East Anglia, and that was where I wrote LIGHTSEEKERS as part of my thesis.

The premise in LIGHTSEEKERS is that three students are beaten and set on fire by a mob angry about the gangsterism they associate with the nearby Okriki university. It was motivated by the real murder of four young men near Port Harcourt. How similar is the situation in your novel to the real case?

Like all works of fiction, LIGHTSEEKERS was inspired by that all-powerful “what if…?” The actual tragedy was one that shook me and many people that saw the videos on social media. In fact, initially, I had wanted to write a nonfiction book based on the real murder of the four young men. The logistics and the moral implications of profiting off the miseries of multiple families and a community made me think twice about that route. And I think that got me thinking about the “what if” aspects of the tragedy. What if it was not a straightforward mob action like everyone thought? What if it was a targeted assassination of one of the boys? What if it was the perfect storm of sorts—a combination of opportunity and the existing systemic conditions that made it all possible? What if…

I think as soon as I went in that direction, the answers I was coming up with took the story in a whole different direction. In the end, I can say that while the story was inspired by my need to make sense of the real tragedy of what Nigerians refer to as Aluu 4, it ended up being a complete work of fiction with little or no bearing on the facts of the story that inspired it. In fact, writing it became a sort of exorcism for me. I was finding it really hard to reconcile my country with this barbaric act. Crazy as it sounds, for some of us in diaspora, we want to hold on to an idealized version of Nigeria—one where everything can be fixed by good governance. We rarely blame the citizenry for the problems, so this tragedy was a wake-up call for me. It was not police brutality or some mayhem caused by bad governance or corruption. This was people being evil to other people. Not an isolated villain but a whole community. I think that set me on a journey of self-reflection about my origins, my place in the world, and what kind of stories I wanted to tell.

Philip Taiwo shares your professional interests, and his expertise in understanding crowd psychology makes him unusual and intriguing as the protagonist of a mystery thriller. He’s rounded out by his ambivalence about Nigeria and his issues with his lawyer wife. Did you set out to develop a character with these attributes, or was Philip more the result of the way you might have approached the actual murder case yourself if you’d been asked to do so?

Philip Taiwo shares your professional interests, and his expertise in understanding crowd psychology makes him unusual and intriguing as the protagonist of a mystery thriller. He’s rounded out by his ambivalence about Nigeria and his issues with his lawyer wife. Did you set out to develop a character with these attributes, or was Philip more the result of the way you might have approached the actual murder case yourself if you’d been asked to do so?

I absolutely set out to create such a character. I am a great believer in the power of intentionality, especially in creative work. I know there is a place for inspiration and all that, but I really think that only happens when you put your intention out there in the universe. So there’s rarely anything about Philip Taiwo that was not carefully planned and well thought through. Of course, there are aspects of his life that I didn’t know how they were going to be relevant later in the story—for instance, the fact that he had twin boys just popped up, and I kept it because I knew it could be used later. A lot of how I develop characters is based off my experience creating and developing TV shows and of course, my background in psychology. The character comes to the story whole and complete, not the other way round.

But you raise a very good point—if this is how I would have approached the case. Absolutely. There is no template for a crime like this, no matter how much experience you have. No matter how much you know, when it comes to crowd psychology, the permutations of cause and effect can be endless. What I really like about my hero is that he is human, hardworking, and committed. He is not a supersmart, super-intuitive investigator like Sherlock. He is trained, and he puts in the work to get to the heart of the case. He is also not a detective in the traditional sense—he is more interested in the why of a crime than the what or how of it. Of course to get to why, he needs to piece the facts of the what and how together, but the real fun happens when he starts uncovering motives. I think I’m like that. The obviousness of what or how does not excite me. It’s the getting to why that really gets my juices flowing.

Philip is asked to investigate what really happened and why by the grieving father of one of the young men. He persuades Philip to take on the job and provides him with resources including a driver, Chika. It turns out that the father, the head of the local police station, and even the driver have more complex agendas of their own. When Philip reaches Okriki, he meets one stone wall after another, and soon the locals want him out. He has to find his way through all these complex relationships. Did you plan all these separate tensions, or did they arise as natural consequences of the type of crime and the setting?

Philip is asked to investigate what really happened and why by the grieving father of one of the young men. He persuades Philip to take on the job and provides him with resources including a driver, Chika. It turns out that the father, the head of the local police station, and even the driver have more complex agendas of their own. When Philip reaches Okriki, he meets one stone wall after another, and soon the locals want him out. He has to find his way through all these complex relationships. Did you plan all these separate tensions, or did they arise as natural consequences of the type of crime and the setting?

I think it’s a combination of both. As of the time I was writing LIGHTSEEKERS, I was exploring the idea of using systems thinking as a tool for plotting a novel. I always felt that the traditional approach to telling stories is a bit inadequate for the complexities that exist in societies like mine—where massive numbers of the population are recovering from the collective trauma of colonization, and in the case of Nigeria, a civil war.

So in writing the novel, I was really interested in how existing systemic structures affect human choices and behavior. To drive this home, I had to create characters that relate with the system in different ways, especially since this is not a story about finding out who did it. To my mind, one of the ways to have a better understanding of what made such a crime possible is to delve into the minds and agendas of the people that surrounded Philip.

I always laugh out loud when I read Goodreads reviews of LIGHTSEEKERS—I know I am not supposed to, but I can’t help myself!—and the readers say “I guessed who the villain was from…” I always want to ask the reviewer: But did you guess why? Could you put the pieces together and come up with a logical reason why this crime was even possible? Why the idea of vigilantes is prevalent on the continent? Why it is okay for the wheels of justice to turn so slowly that people have to take the law into their hands? Why a country that’s one of the world’s largest oil producers is one of the poorest? At what point was the reader able to, say, predict the conclusions Philip came to? What I am saying is, if you approach the story thinking you want to solve the mystery of who did it, then you miss the whole point of the story.

I think of it like a Christopher Nolan movie—complex, with layers of meaning and interpretation at environmental, physical, psychological, and sociological levels. Throw in politics, economic realities with a large dose of history, and you might be able to understand why LIGHTSEEKERS was designed the way it was. Getting it, or figuring out the crime was not the goal but rather it was my attempt to point a torchlight at a tragedy and use it to reveal the humanity that connects us all. I’m making peace with the fact that many crime readers do not have the patience with that level of complexity. But I’m not sure I can do it any other way.

Certainly, mob violence can happen anywhere in the world and in any culture, but LIGHTSEEKERS couldn’t be set anywhere else. The powerful tribal hierarchies, the university fraternities/cults/gangs, and the resulting relationship with the townspeople in the area, the mixture of religions, the heat, the food, the traffic, all give a powerful sense of place. Was one aim of the book to reveal aspects of modern rural Nigeria?

Certainly, mob violence can happen anywhere in the world and in any culture, but LIGHTSEEKERS couldn’t be set anywhere else. The powerful tribal hierarchies, the university fraternities/cults/gangs, and the resulting relationship with the townspeople in the area, the mixture of religions, the heat, the food, the traffic, all give a powerful sense of place. Was one aim of the book to reveal aspects of modern rural Nigeria?

I’m not sure it was one of the aims as much as THE aim. I really was tired of these expectations of the kinds of novels that should come out of the continent. I love the opportunity crime fiction gives to travel across different classes, through different lenses. Crime affects everyone, no matter your ethnic group, race, gender, or age. Few literary genres offer that kind of opportunity to let the reader transverse through a community or a group of people. I think of that seminal novel, Sacred Games by Vikram Chandra. My aim was to achieve that level of complexity about Nigeria, but I didn’t think I was smart enough (like Chandra) to take on the whole country, so I settled for a fictional town that I could manage.

So yes, I wanted the reader to see a bit of Nigeria that’s not quite prime time viewing on CNN. I wanted the reader to know that people, real people, with real experiences live in these places, and their stories are important. But most of all, that the reasons why people do heinous things are not as alien as many would like to believe. There’s no “us and those people.” Especially in this age of social media, we are all connected, and the triggers of trauma can be quite similar.

As the story progresses, there is a subplot involving a mysterious character, John Paul. While at first, he seems almost unrelated to the main story, we see some events from his point of view, sometimes in first person present and sometimes in third person past. It’s an unusual way of writing and works here remarkably well. Can you explain what brought you to this approach?

As the story progresses, there is a subplot involving a mysterious character, John Paul. While at first, he seems almost unrelated to the main story, we see some events from his point of view, sometimes in first person present and sometimes in third person past. It’s an unusual way of writing and works here remarkably well. Can you explain what brought you to this approach?

Oh, thank you for saying this. It was the part of the story that I believed in the most and found hardest to craft. In fact, quite a number of the critics imply that this gave the novel an uneven feel that didn’t work. I opine that such “unevenness” was exactly what I was gunning for.

John Paul is not in the real and traditional sense, a character like everyone else in the novel. In fact, he is not as 3D as the classic character/villain, and his point of view is so off-center that it’s hard to relate to him. So why did I create him? And why did his point of view need to be seen/heard? Because essentially, he is a composite. To my mind, he is Nigeria: fractured, borderline schizoid, suffering from massive PTSD and made up of un-whole, unharmonized parts of self. He is a symbol of the systemic breakdown I wanted to use as part of the explanation that enabled such a crime in the first place.

To approach (reading) John Paul as a character in the traditional sense would be too simplistic. But when you superimpose a whole zeitgeist on him, and see him as a symbol of the larger institutions that make up a society for good or bad, then you start to get it. Not fully, but even a part understanding of the magnificent, complicated, disparate, and troubled miracle called Nigeria would be enough for me.

We’d love to know what Philip will be involved with next. Will you be bringing him back in the future? Either way, can you tell us anything about your next project?

I just completed a first draft of the sequel to LIGHTSEEKERS, but I am still holding on to it—a bit nervous about submitting to my publisher. Everything you heard about The Difficult Second Novel is true. Anyway, I can’t say too much about it now, but I can reveal that the events take place almost a year after the Okriki 3 case, and Philip again goes into the investigation naïvely thinking it was open and shut until things get very, very complicated.

Of course, he has Chika, his wife, and some of his students to navigate his way through the investigation. He is also a bit more Nigeria-savvy, so things move relatively faster than in LIGHTSEEKERS. Religion and patriarchy are some of the themes I explored in the book while applying a lot of the things I learnt while writing the first book. I hope it shows and my editors like the story as much I do.