Paying Homage to British Dialect

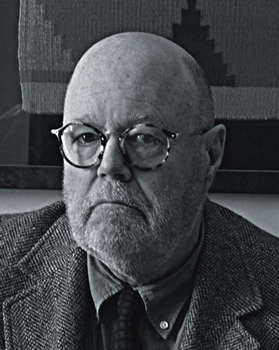

In four decades of writing, Stephen Hunter has developed a reputation for deep characters, great action, and, of course, snipers. Point of Impact in 1993 introduced the world to series character Bob Lee Swagger—and the author has continued to captivate readers.

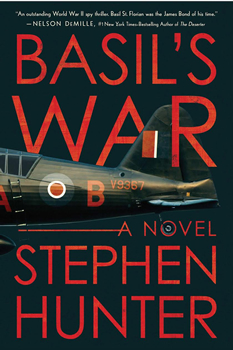

His latest, BASIL’S WAR, introduces British agent Basil St. Florian, tasked with going undercover to recover a rare manuscript that may hold the answers to breaking a code that will save millions. St. Florian penetrates Nazi-occupied France, using his wit to engage and evade the Abwehr and Nazi agents pursuing him. The key components of a thriller are definitely here—parachuting, gun battles, jumping from trains—yet Hunter also brings history, humor, and humanity to the writing, making the story even more engaging.

In this exclusive interview with The Big Thrill, Hunter explains how his love of British dialect inspired his latest thriller, the kind of research that goes into his work, and how his writing process has changed over the past four decades.

What inspired BASIL’S WAR?

It comes from my love of British dialect. I have this Chicago twang that will not go away, even 60 years after I left Chicago, and I always sounded like a drunken chimpanzee when I opened my mouth. I just grew up loving the English accents in the movies, and I love the English rhythms and the English idioms. I enjoy desperately, and I’m attracted to, that voice in fiction. I’ve written two or three stories, I guess beginning with one of the early Basil stories, as if I went to Balliol College at Oxford. I don’t know if I’ve convinced Brits that I’m British, but I convinced myself that I’m British. I just love to write in that voice. That’s where it came from, and I’m always looking for stories that will allow me to pretend to be English.

In this particular case, some years ago, Otto Penzler of Mysterious Books asked me to write a piece about some espionage episode for a book called Agents of Treachery. I created this character, and I wrote that piece in the British dialect. I could never get it out of my mind. Some years later, he asked me to expand that piece into a larger story, and for me it was an excuse to jump back into the voice and once again pretend I’d gone to Balliol College. I should be paying Otto for the fun, although he is paying me for the fun I had. Hence, the book, which was just a joy to work on. Doing this stuff is fun!

It was fun to read as well. Publishers Weekly described it as a “breezy, boys’ adventure” and I agree. I was entertained, and I could tell that you had fun writing it.

It’s what I would call “an entertainment.” It’s the dichotomy that Graham Greene evinced; he had novels and then what he called “entertainments.” A famous entertainment was This Gun for Hire, but I think BASIL’S WAR is much cheerier.

You mentioned the British voice—and of course, that comes out in your novel I, Ripper as well. What is the research? Is it from your film background? (Hunter won the Pulitzer Prize in 2003 for film criticism.)

It’s easy to research facts, especially with the internet, so much so that it’s inexcusable to have a factual error these days. Voices, you have to have an ear and a rhythm for it. The truth is, instead of going to Balliol College, I went to MGM College. I speak a kind of movie British, and it’s over-peppered with signatures of British dialect. There’s a lot of “old mans” and the word “then” pops up meaning “now.” I don’t know why they do that, and I don’t know why I like it so much, but there’s 200 “thens” in this book. Their use of language is so droll, and so dry, and so understated. To my ears, it’s magical! I have fun doing my version of it, understanding that it’s an entertainment. I understand that a true Balliol graduate might read it and say, “This chap really doesn’t have it down quite right” or “Nice try, old man.” That’s okay, because it’s not literal. It’s an homage, a tribute. It’s a reflection of preferences in literature and film over the years.

Can you tell us a little about the research and how far you like to go with it? How much of it makes its way into your finished works?

I think the most important fact in terms of craft about research is to do a lot, but not too much. What you’re looking for is resonant, salient, vivid facts, not comatose facts. In other words, if you get 10 interesting facts, pick the best one and throw that at the reader, as opposed to listing the other nine. That tends to act as a literary chloroform. Don’t let the research become an end. You have to be in control of the research; it cannot be in control of you.

When I do book events, I frequently hear from people who have a book inside them, but they can’t get to it because they’re still doing the research. There comes a time when you do as much research as you think you need and then say, “that’s it” and write the damned story.

I am an index researcher. That’s to say, I don’t read books. I read indexes. The book I’m writing now is set in the Battle of Normandy in early July of 1944. I have 50 books on that battle of which I will have read none but of which I will have looked up the words “bocage” and “snipers,” and I will have read the two pages in each book that deal with that topic. The grace of that method is that it gets you writing fast, but the downside is that you may miss context. For example, I did a book on the Spanish Civil War that was set in the year 1936, and my joke is, and it’s not quite true, that I have no idea who won the Spanish Civil War because I did all of my research stopping before the end. That’s an exaggeration, but you do need to be surgical and laser-like in your research.

You’re into your fourth decade of writing thrillers. What do you do differently now? What is that one thing that you’d go back and tell yourself?

I’m not so cognizant of rules. When I began, I stuck to a very strict rules of point of view, author’s voice, alternative chapters, switches between narrative lines. It was all very programmatic. I feel, at this point, much more relaxed in terms of form, and that means I’m much more relaxed in terms of story. I am more willing to just let it flow; however, I get most of my effects from the relationship between two narratives. The timing of that is very important, and I feel a little too orthodox in that. That can also be artificial, and I’m trying to force myself to say, “Steve, it’s all right to do ABAABABBAA,” just to relax and let the story happen as opposed to relying on a too formalized structure.

Any advice for those getting started?

I’ve said this before. The most important words of any book are “the” and “end.” You’ve got to finish the damned thing. You can’t lose your way halfway through, and you can’t lose your concentration. You just have to keep soldiering on. You have to accept that it may take awhile to find a rhythm and the voices and the action and the points of view that make it work. You’re going to have slumps, and you’re going to write stuff that you know is garbage. The first draft of one of the books, it was so awful that it was funny. I thought to myself, “If anyone saw this, they would ban me from typewriters forever!”

You have to show up and do it. You have to have faith in yourself that eventually it’s going to get interesting. Point of Impact, my pivotal book, didn’t get interesting until year three and the first two years were mostly gunfights and committee meetings. Whenever I was stuck, I would write one of those. There came a moment when I had to get serious and cut 80 percent, and yet, when I cut that, I thought, three years into it, This is pretty good. That eventually became a very significant book for me, and I only got it because I sat my you-know-what down in the chair every night. You just gotta keep going.