Deep Cuts

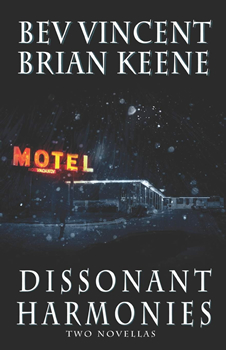

In music, “dissonant harmonies” are unstable combinations of pitches that often leave the listener feeling tense or uneasy. It’s a perfect metaphor for a new duology of novellas from horror stalwarts Bev Vincent and Brian Keene, presented in a single volume from Cemetery Dance.

In Vincent’s novella, “The Dead of Winter,” two brothers investigate a series of unexplained disappearances as a brutal snowstorm bears down on their already-isolated hometown. When one of the brothers makes a bizarre discovery in the basement of an apartment building, they realize they aren’t dealing with anything as mundane as a serial killer. Vincent’s slow-burn horror tale is heavy on atmosphere and suspense, leaning into the tropes and rhythms of crime fiction as it builds to a satisfyingly unhinged conclusion.

Keene’s contribution, “The Motel at the End of the World,” centers on the Mandela effect, a shared false-memory phenomenon that causes significant slices of the population to remember something differently than how it occurred. (The name refers to Nelson Mandela; many people insist they remember the South African leader dying in prison in the 1980s even though he was released in 1990, served as the president of South Africa from ’94 to ’99, and died in 2013.) Short and savage, Keene’s tale of reality fraying at the edges is a devastating take on apocalyptic fiction that plays out entirely in the confines of a single motel room.

Though they’re wildly different in tone, style, and subject matter, the novellas of DISSONANT HARMONIES share a common genesis: each author’s story was inspired by a playlist created for him by the other writer. The project was originally conceived more than a decade ago, but fate (mostly in the form of Stephen King) conspired to keep it out of your TBR pile until this year, with Cemetery Dance’s surprise trade-paperback release in March. (A signed, limited-edition hardcover run is forthcoming, exclusively available to members of the specialty press’s Collectors Club.)

In this joint interview with The Big Thrill, Vincent and Keene talk about the project’s winding path to publication, the role music has played in their creative processes, and why the project’s lengthy gestation was Stephen King’s fault (but not Paul Tremblay’s).

This project has been a long time in the making—you first started talking about it back in 2007. I’ve certainly let a lot of ideas fall through the cracks in the last 14 years. What’s kept you both coming back to this one?

Bev Vincent: It helped that we saw each other on a regular basis over the years, usually at the Necon conference in Rhode Island and, more recently, at KillerCon in Austin. Every time we got together, we’d revisit the idea until we finally got around to sharing our playlists with each other. That was the real kickoff for the project. The idea for the book did morph a bit over the years, though. Initially we thought we were going to do a short story collection. But basically it was all about the music, which plays such an important part in our creative lives.

Brian Keene: Bev’s being kind and not throwing me under the bus. As he says, the playlists were the real kickoff, but even after we’d made those, there was still a big delay, and that falls squarely on me. In truth, “The Motel at the End of the World” was the second novella I ended up writing for this book. The first novella—also directly inspired by Bev’s playlist—was very close to being finished. I probably had 2,000 or so words to go on it. And then Stephen King’s novella “N” came out, and I read it that weekend, and the themes and such were just way too similar. So I shelved that novella, intending to cannibalize it for parts later. And then I listened to Bev’s playlist off and on again for a few months and waited for inspiration to strike twice. Luckily it did.

But then what made it even funnier is, while I was working on the novella, Paul Tremblay came to visit for a weekend. And we were sitting in my living room, and he was telling me the then unannounced title for his next novel, The Cabin at the End of the World, and I laughed, and told him we were just going to have to share similar titles, because there was no way I was going to make Bev wait while I wrote a third novella. (laughs)

When you were creating playlists for each other, what criteria did you use to select songs?

BV: We didn’t set any rules or guidelines for how we would select the songs. It was left completely up to the individual. I wanted to pick mostly songs that Brian probably hadn’t heard before, with a few exceptions. Some of those were deep cuts, B-sides, or rarities from musicians I knew he liked. In other cases, I picked musicians I was pretty sure weren’t on his radar—groups like Shpongle, who have become personal favorites to listen to while writing.

BK: Exactly. Our core musical tastes vary, but both of us are eclectic in what we listen to, so we have overlapping likes—Supertramp, Genesis, Alan Parsons Project… stuff like that. But I also knew that Bev probably wasn’t listening to much Ice-T or Faith No More or Shooter Jennings, for example, so I wanted to include songs by them that he might actually dig if he heard them. My only other criteria was to set an overall mood of impending doom and hopelessness, and have it ramp up with each song. And in reading “The Dead of Winter,” I think I do see that overall mood reflected.

Can either of you pinpoint a song from the playlist you were given that was particularly influential in shaping your novella?

BV: Probably “I See a Darkness” by Johnny Cash, although I’d be hard pressed to draw a straight line between that song and “The Dead of Winter.” For me, music is mostly about creating ambience. I’m often not conscious of what’s playing, and I’ve been known to go into a zone to the extent that I don’t hear entire songs. But they’re contributing to the mood while I’m working.

BK: For the second—and published—novella, there were two in particular. “My Crime of Passion” by Mike & The Mechanics, and “People Are Like Suns” by Crowded House. Juxtaposed against each other, the idea sprang out pretty much in its entirety.

Besides DISSONANT HARMONIES, what are some other ways music has influenced your writing?

BV: I once wrote a novel while listening to nothing but Supertramp! A few of my short stories were inspired by specific songs or groups of songs. My story “Wake Me Up for Meals” was originally written for an anthology inspired by the music of Warren Zevon. The anthology never got off the ground, so I ended up selling it to Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. My Al Blanchard Award winning story “The Bank Job” was inspired by a couple of songs by Fountains of Wayne. I have occasionally considered doing a short story collection inspired by FoW—so many of their songs are perfect little stories.

BK: I’ve got a recurring character that has appeared in a half dozen short stories and several novels—a serial killer known as The Exit. His name, and his mission—and indeed, my entire idea for him—came to me while listening to Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor whisper “I am an exit…” through my stereo speakers.

My most recent novel, With Teeth, was written exclusively to “Beauty in Falling Leaves”—a 16-minute song by a doom metal band called YOB.

Did you communicate with one another about your novellas as you were writing them?

BV: I’d occasionally get an email from Brian saying he was working on something. My novella happened really quickly—It was only a month between the first line until the last for the first draft. I don’t think I told Brian anything about it while I was working on it, and I even sent it to a couple of first readers before I shared it with him.

BK: After making Bev wait so long, I was afraid to say much about it, other than “Hey, I’m working on it. I promise!” I think at one point I said, “It has to do with the Mandela effect and quantum theory and these two down-on-their-luck characters straight out of a Bruce Springsteen or Eminem song.” But that’s all I said, because I wasn’t sure… I knew what the ending of the novella would be, but I wasn’t sure what road I was going to take to get there.

How did Cemetery Dance get involved?

BV: We had another publisher lined up to do the book, someone Brian had worked with before, but that blew up—I’ll leave it to Brian to share as much or as little of that story as he wants! In the aftermath, we got in touch with Richard Chizmar to see if he was interested in the book. I’ve been a contributing editor with CD for 20 years, and they’ve published limited editions of a few of my books, as well as taking several of my stories for the magazine and anthologies. They seemed like a perfect fit for this book, and Rich was enthusiastic out of the gate. He decided to publish a signed, limited hardcover as part of Cemetery Dance’s Collector’s Club and we were very pleased by the response to that offering—over a thousand copies sold.

BK: Yeah, less said about the initial one the better. But like Bev, I’ve been friends with Rich for years, and have published a lot with Cemetery Dance. We knew he’d treat us right, and like Bev said, he was eager to do this. He understood this experiment right away.

Bev, I had no idea where “Dead of Winter” was going until it got there, and according to your story notes, neither did you. Brian, your story notes imply that you took the opposite approach—that you knew where you would end up and had to figure out how to get there. Is that how writing fiction usually shakes out for each of you?

BV: I hardly ever know where I’m going with a story. I start when I have a couple of complementary ideas that seem to fit together and an understanding of who at least the main character is and what he or she wants. After that, it’s an act of faith that the story will roll out before me as I go. Knowing Brian’s appreciation of Hunter S. Thompson, I had the idea to start the story with a loose homage to Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: a character in the midst of a drug trip. I usually ended each day’s writing with a general idea of what would happen next. Sometimes the story development took place in the shower after I finished writing and was preparing to transition to my day job. In other cases, it happened in the hour or so before I woke up the following morning, as my mind got me ready for another day of writing. That’s fairly typical for me. It is a true mystery, though, where this stuff comes from. You just start writing and out come these words and events.

BK: It’s different for me every time. I never outline. I loathe outlines. Outlines to me are what the Q conspiracy theory is to common sense and logic. Sometimes, I’ll have an idea of what the ending is, and I’ll write toward that goal. Other times, I’m making the whole thing up as I go along. My only hard and fast rules are that I need to know the opening sentence before I can start, and I need to know who the characters are before I can start as well. Particularly if I’m writing horror. Horror readers expect you to incite fear or dread, but you can’t do that if they aren’t emotionally invested in your characters. So I have to be invested in them first.

Bev, you mention in your story notes that you wrote “Dead of Winter” in longhand and then dictated it to your word processing program. How did that method affect your creative process, and will you use it again?

BV: I have converted almost exclusively to that approach for fiction. Virtually all the short stories I’ve written since finishing “The Dead of Winter” were drafted in longhand, either in a journal or on a notepad. The dictation software in Word has gotten really good in recent years, and I’ve developed a rhythm in reading the stories into the computer, where you also have to specify line breaks and punctuation. In the past, reading a story out loud was often a part of my editing process—now it takes place earlier in the creative journey. But writing longhand allows me to get away from the computer. I spend so many hours in front of one each day that it’s a nice break. However, I still use it for writing non-fiction, in large part because I have to look things up as I’m writing, so being at the computer is important.

Brian, “The Motel at the End of the World” was inspired by the conspiracy theory known as the Mandela effect, and in your story notes you mention that you “love a good conspiracy theory.” Now that conspiracy theories have become such a prominent part of American politics, do you find yourself thinking of them differently?

BK: (Groans) I hate what has become of conspiracy theory culture. Gone are the days of UFO research and studying the minutiae of the Kennedy assassination and searching for the Loch Ness Monster. At some point in the early nineties, we allowed conspiracy theory culture to get co-opted by White supremacists, anti-Semites, and snake oil salesman like that human scab Alex Jones. And sadly, I don’t think more “mainstream” conspiracy theorists will ever be able to successfully reclaim them, because it’s so embedded in the national psyche now. Discussion of conspiracy theories has been so overrun by the alt-right and other extremists at this point that it seems pointless to talk about UFOs or Kennedy.

Of course, maybe that’s what the powers that be wanted to happen. Maybe that’s the conspiracy! (laughs)

Brian, I couldn’t help laughing at your story notes, where you reveal that Stephen King mucked things up for you while you were working on your half of DISSONANT HARMONIES. Bev, King looms in the background of your contribution as well, and one of your characters references a movie inspired by a King novella. Is it even possible to write horror fiction that isn’t somehow influenced by King?

BK: I would say it’s no more possible for a horror writer today to not be influenced by King and perhaps Clive Barker or Jack Ketchum than it was for King, Barker, and Ketchum not to be influenced by Robert Bloch and Richard Matheson, or for Bloch and Matheson to be influenced by Lovecraft and Poe, and so on. And I think that’s normal. And I think it makes for a healthy genre, overall. What’s important is the individual voice, the individual twist—putting your individual stamp on tropes that horror writers have been using since the days of cave paintings.

BV: It’s probably not possible, and of course I’ve read everything King has ever written, but I have to say that there’s little in my novella that I’m aware of being directly influenced by King beyond the characters’ awareness of him as an author. My main inspiration comes from crime fiction, as it happens—I can’t wait to see if readers recognize the inspiration for my two protagonists.

What’s next for each of you?

BV: After a slow beginning to 2020, I found my rhythm again, and I’ve written several short stories that will be published in the coming months. This past month I’ve been working on a story for an anthology for a gaming company’s anthology. That’s been fascinating—a little like writing a story in a foreign language because I’ve had to learn so much about this far-future science fiction universe. I also explored self-publishing for the first time, releasing a long crime story called “The Ogilvy Affair” on Amazon. My agent is currently reading what I hope will be my first published novel, and I’m about to embark on a screenwriting gig adapting and expanding one of my short stories. I’m very excited about what the next couple of years have in store!

BK: With Teeth comes out in paperback in June, followed by a paperback release of Suburban Gothic (co-written with Bryan Smith) in July. At some point this year, a paperback release of Curse of the Bastards, the third book in a sword and sorcery series I co-write with Steven L. Shrewsbury, is supposed to come out, but I’m not sure when. And then, at the end of the year, a new hardcover re-release of my first crime novel, Terminal, and a hardcover release of a new novel called The Seven, which I’m very excited for. In between those, I’m finishing up a massive graphic novel based on characters and situations created by Stephen King and Richard Chizmar, and I have a few other irons in the fire. I try not to slow down. I probably should, but I’m not happy if I’m not writing.