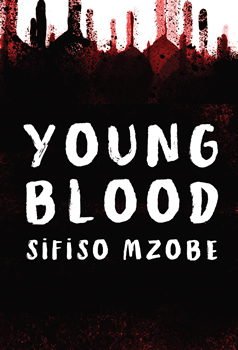

Africa Scene: Sifiso Mzobe

Deep Into the Illegal South African Car Trade

In Sifiso Mzobe’s new thriller, Sipho, a true “Young Blood”—a youth with nothing to lose—drops out of high school and joins a car-stealing syndicate. The novel, part crime saga, part coming-of-age story, charts Sipho’s few months while in this syndicate, taking the reader on an emotional journey as he’s pulled deeper into the vicious underbelly of the illegal South African township car trade.

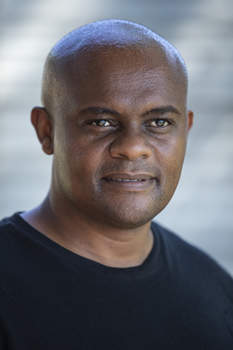

In this interview for The Big Thrill, author Mzobe provides insight into what inspired this compelling story and its diverse cast of characters.

Sipho lives in the township of Umlazi, an informal settlement on the outskirts of the city of Durban. His brick home overlooks Power, a shanty town of tin structures. Did this truly South African setting—one of poverty and hardship—inspire the story? Or did you have Sipho in mind when you started writing?

When I started writing this story, the characters and setting were very crisp in my mind. The proximity of Power, the shanty section, and the more developed section consisting of brick houses where Sipho lives is what you see in most Black townships of South Africa. People flock to townships from rural areas so they can be near job opportunities as townships are closer to cities. Shanty sections in townships spring from that, and they just keep growing. It’s been like that since I was very young.

In Umlazi you find shanty sections, a few mansions, and a lot of four-room houses. Four-room houses were built by the apartheid government when they forcibly removed Black people from the cities. The term four-room is deceiving. It does not describe a house with four bedrooms—there are two small bedrooms, a small kitchen, a toilet, and another room. People from these different social classes co-exist in Umlazi Township.

Indeed, YOUNG BLOOD is very much the story of Umlazi—one could describe the township as a character in and of itself. How did you bring it to life?

I witnessed the political civil war that ravaged Umlazi in the 1980s when I was a child. As a teenager I felt the palpable optimism that bubbled in Umlazi after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison at the dawn of the democratic South Africa. In my adult years I’m witnessing disillusion in my people as the promises made in 1994 when Nelson Mandela became our president remain unfulfilled.

The raw, vile, perverse apartheid of the previous government has changed its spots to become another version; the apartheid is purely economic now. Black people suffered then, and the majority of people suffering today are Black. Unemployment is high, and most of those who work don’t make enough to live comfortably. It is in this environment that the people of Umlazi Township try to go about their daily lives and make ends meet and thrive.

The setting is what I see every day. It’s the same with the main character—Siphos are all around me in my world. The character and the setting inspired the story simultaneously. In telling the story I wanted to put the reader inside Umlazi Township.

To get to Sipho then, your “Young Blood,” he grows up in this setting, abandons school in Grade 10, and soon gets caught up in what can be described as a “wild life.” What was the early spark for his character?

I thought it would be interesting to develop a character like Sipho who drops out of school, who is a mechanic taught to fix cars by his ex-convict father, and is roped into a car-stealing syndicate.

I went to school with a lot of people who turned out to be “Young Bloods,” like Sipho. I wanted to explore why I took this path, of writing, and they took the other path, of crime. So I started to look deeper, beyond the headlines and statistics.

I see a lot of people like Sipho who have an intelligence that is not academic but social. There are sections in Umlazi where just making it into adulthood is a great achievement. Places where poverty is just overwhelming. Where the majority of young men have been to prison at one point or another in their lives. It was intentional to have Sipho come from a section of “four rooms” because I wanted to show the reader how that class of township dweller struggles. And it was also intentional to have Musa, Sipho’s best friend, come from Power, the shanty town, as his struggles are even greater.

Indeed, it is Musa who first gets Sipho involved in the car-stealing syndicate. However, considering that Sipho’s parents are hard-working, his father is a mechanic (though an ex-convict and a former captain in a prison gang), his younger sister is sweet and adoring, his mother God-fearing, why did Sipho choose a life of crime? The family have a better life than many, certainly better than those who live in Power.

The life of crime is seductive. He sees that hard-working people can’t afford the expensive cars his criminal friends have, and the flashy clothes. He is ambitious, so if school doesn’t do it, he’ll take the other route on offer.

Money rules the world; love doesn’t bring food to the table. It is that simple to him. Sipho knows he is loved, but he also knows the reality of how the world works. His family is just making ends meet, so he believes that by making money, even illegally, he will help his family. I tried to show their struggles in the first chapter—it has taken them years to just build a wall around their house. It takes them a long time to afford to buy the blue paint for that wall. They cannot afford to buy a gate. His mother works as a cleaner at a hospital; his father is a backyard mechanic. Most criminals come from families like these, families that barely make ends meet.

Lately in South Africa we have this phenomenon of the “unemployed graduate.” There are just not enough jobs—even if you have completed your diploma or degree, it is not guaranteed that you will find a job. It’s easy for people like Sipho, who is not gifted academically, to look at his future prospects and lose all hope. If education doesn’t guarantee success, then what will become of him, not being educated?

I found that in researching these guys, car thieves and armed robbers are usually ordinary people pushed by circumstances into a life of crime. And things go downhill from there.

In Sipho’s quest for success, he visits a traditional healer to get advice before joining the syndicate. I wondered if this reflects reality?

Yes, indeed. You have to understand that most Zulu people, who make up the majority of the population in the province of KwaZulu-Natal where Umlazi Township is situated, have kept their traditional belief system. This belief system is very much structured like most religions, in fact. It has a higher power, a prophet, and the one who spreads the message (that would be the priest or pastor in Christianity or an imam in Muslim communities). This traditional belief system relies heavily on miracles and the afterlife, just like most religions.

All the people I interviewed during research regularly consult an inyanga or sangoma. They get medicine for protection. They even pay the inyanga or isangoma after a successful “job,” just like a tithe in church.

In Sipho’s case, Old Man Mbatha has helped him before, when he had to heal after a traumatic experience, so he returns to him now in order to approach the ancestors for protection.

As Sipho’s desire for money grows—and he’s getting lots of it, to meet his habits, to keep his girlfriend Nana “sweet”—he becomes obsessed by his fast and furious love affair with cars. Could one generally describe this life—as a mechanic, a car thief—as a township subculture?

A car in Umlazi Township is both a symbol of success and freedom. You turn the ignition and 20 minutes later you are at the beach or in the city, Durban. But more importantly, Umlazi Township is the car-stealing capital of our province in South Africa.

I researched a lot about how it comes about that young men become car thieves. Just like Sipho, most of them are good drivers, they have an emotional connection with the car engine. This is the only thing they think they are good at. They drive like stunt men, spinning cars in the dead of night. It really is a sight to behold. Sipho often goes “night-riding.”

Sipho moves quickly from stealing cars to selling drugs, in a context that is progressively more violent. “Backstabbing, double-crossing, jail and death—the givens in the life he has chosen.” How did you research this?

I talked to a number of hijackers, hitmen in the taxi industry, and armed robbers. They told me about how there was no honor among thieves. I heard a lot about double-crossing and revenge meted for that double-crossing. And revenge for that revenge. Unbelievable snowballing effect. One guy told me that he would never do armed robbery because he’s scared he’d have to kill all his accomplices after dividing the money. He said he never trusts another crook. I also spoke to a detective who told me that a lot of criminals are informants.

In listening to car hijackers I heard about double-crossing. A hijacked car sometimes disappears from where it was hidden only to find that one of those guys has sold it and taken all the money for himself.

At one stage, Sipho says, “In a township we grow up around killers, so there is really nothing to fear.” The story is peppered with several truly ruthless characters. Sibani, the “boss” of the syndicate, is a true psychopath. I’m struck by Sipho’s relative calm as he witnesses execution-style shootings. Is Sipho desensitized to violence?

Growing up in the township, witnessing crime and brutality gives thick skin. Violence desensitizes and kills something inside. Many of the criminals I interviewed know very well what is in store, that death or prison is the likely result of the life they have chosen. This is the scariest part of it all: that people are so desperate for money that they are willing to risk their lives. They know it can and will likely backfire at any time, but they hope it doesn’t.

Generally speaking, and considering South Africa in particular, is it true that violence begets violence?

All the violence meted on Black people for generations keeps getting passed on. And it comes back to haunt the country with each generation. When we were kids during the political civil war between ANC and IFP in Umlazi, we saw brutality that a human being, let alone a child, is never supposed to see. You’d see a mob burn a man to death. It happened several times. One time we had to step over dead bodies on our way to primary school.

Even today, every few months there is a spate of killings, hits in broad daylight—taxi bosses taking each other out. There are hits over drug turf. Recently gangsters who were involved in extorting contractors are getting killed one by one. These are things you see coming from picking up your child from school or coming back from work—cars dented by sprays of bullet holes.

Our own parents had witnessed the Sharpeville Massacre and many other atrocities on top of the violence of being degraded and being seen as subhuman on a daily basis. Even the mismanagement of the country today is violence against its people. It just keeps going. It never lets up, it just keeps begetting more violence.

As the YOUNG BLOOD crime spree progresses, the rival gang, the Cold Hearts, true blood-spilling psychopaths, do the unthinkable in the story, forcing Musa and Mdala (another vital character, in his 50s and somewhat a leader of the young men) on a quest for revenge. Sipho sees good friends killed. How does this impact him?

Sipho is lucky to have a father who has a history in South African Numbers Gang as part of the 26s gang, and his childhood friend, Musa, who tells him about the brutal side of being a numbers gang member. Numbers gangs, in particular, are entrenched in many young Black and Coloured males in the townships. It just shows that people want to belong to something, even a brutal brotherhood.

The numbers gangs are gangs in South African prisons. Gang culture is also prevalent outside of prison. It is something I grew up witnessing a lot in Umlazi. The gangs are made up of the 26s—the money makers, the 27s—the killers and keepers of gang law, and the 28s—divided into gold and silver lines. The gold being the warriors, the silver are the sex slaves of the gold.

At least Sipho is surrounded by people who warn him about taking up gang membership, unlike many young men who are seduced by gang culture and fall into it blindly and never get out.

Sipho is not yet a hardened criminal. He still has a heart, so he has the luxury of feeling devastated when for example, Musa is killed. In feeling devastated he starts to weigh up his decisions and the impact they will soon have on the ones he loves.

And so he begins to change…

Finally, congratulations on the many awards YOUNG BLOOD has garnered, including the Sunday Times Fiction Award. How did that impact on you as a writer?

It put a lot of pressure on me, at first, to come up with the next novel. But over time I have come to embrace these accolades. The recognition for my work has opened up a lot of opportunities for me, and I am immensely grateful. I do a lot of work now mentoring young writers, doing translations, and facilitating writing workshops for an organization called the Fundza Literacy Trust that promotes reading and writing for pleasure among young adults in South Africa. This in turn means all the work I do is in one way or another just about writing. And that is all I have ever wanted to do in my life—to earn a living by writing.

- Africa Scene: Nana-Ama Danquah - December 31, 2021

- Africa Scene: Sifiso Mzobe - April 30, 2021

- Africa Scene: Natalie Conyer - December 18, 2020