The Devil You Know

In his acclaimed 2019 supernatural thriller The Remaking, Clay McLeod Chapman explored how a ghost story might evolve along with the modes of telling it, tracing a tragic local legend as it went from a campfire tale to a pair of ill-fated movie productions to a true-crime podcast, leaving the lives of its tellers forever altered in the process.

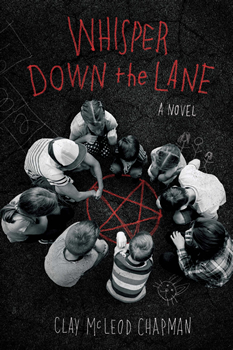

With his devastating new psychological horror novel WHISPER DOWN THE LANE, Chapman is concerned with an altogether different—and infinitely more dangerous—kind of storytelling.

“I wanted to stick with the persnickety malleability of a rumor and how it can pervert itself with each retelling,” he says. “My kid tells me a funny story and I tell my wife and then my wife tells our neighbor and then she tells her next-door-neighbor and then he tweets something about it and then someone retweets it and on and on and on… and suddenly, it’s no longer my kid’s story. It’s the world’s now. We forsake our authorship over it because it belongs to the myriad of mouths who keep spreading it. A curse.”

Chapman didn’t have to look far for a real-life example of a rumor that took on a horrifying life of its own. American history is rife with examples of bizarre, baseless accusations that have led to disastrous consequences, from the Salem witch trials to the still-unfolding grotesqueries of QAnon. In WHISPER DOWN THE LANE, Chapman evokes an episode that played out during his own childhood: the Satanic Panic of the 1980s.

“I was a child of the Spielbergian ’80s. Born in the ’70s, I was reared on Gremlins and E.T. and everything in between,” Chapman says. “Satanic Panic was steeped into our suburban culture. It was all around us, in our parents’ conversations, whispered along our block, even in the ground itself, it seemed. As kids, we were pretty much allowed to risk life and limb on our Schwinns every day after school, and yet, there was this pervading malaise that seemed to spread along our block, some suburban boogeyman we were told to be afraid of, just to keep us safe. The white van with no windows.”

WHISPER DOWN THE LANE—named for the children’s game more popularly known in North America as “telephone”—unfolds in dual timelines. In the 1980s, five-year-old Sean is simply trying to please his anxious mother when he tells a story he can’t take back, inadvertently accusing his teacher of abuse. Sean’s lie snowballs and spreads through his insular community, with horrific results. In 2013, Sean, now in his 30s and going by the name Richard, is still struggling to put the episode behind him. Richard is an art teacher at an exclusive school and a devoted stepfather to five-year-old Elijah, but his life begins to unravel when it becomes clear that the lies he told all those years ago aren’t done with him. First the school pet is dismembered in what appears to be a ritual sacrifice. Later, Richard’s students blame a classmate named “Sean” for mysterious bruises on their bodies, but there’s no Sean in Richard’s class.

The story is shaped by the McMartin trial of the 1980s, which saw several California preschool workers accused of Satanic ritual abuse of children in their care. All charges were eventually dropped, but the damage was done, lives and reputations ruined. Others accused in similar cases throughout the country were even less fortunate; dozens were sent to prison for crimes that probably never happened. Some are still serving life sentences.

The true genesis of the book, though, came from a dinnertime conversation McLeod had with his mother. The author mentioned an “odd childhood memory,” only to be told by his mom that it never happened. Chapman found it unnerving that something that felt so real to him might’ve been a product of his imagination. “What other memories were untrue?” he wondered. “Could I trust my own recollection of my past?”

That sense of disorientation permeates every page of WHISPER DOWN THE LANE, making for a profoundly unsettling read. By the time the book’s secrets are revealed in the final scenes, it’s hard to say which explanation is more terrifying: that Sean’s phantasmic stories might somehow be coming true, or that Richard is experiencing a psychotic break.

According to Chapman, writing the book was no less grueling than reading it. “It was utterly terrifying,” he says. “Perhaps the scariest experience I’ve ever had writing something. I felt like there was no safety net. No guard rails. I couldn’t get out of my head and the voice in my head was constantly full of self-doubt. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. Not the greatest way to write a novel, I know, but when you’re working on a piece of psychological horror… well, I guess it’s okay.”

Though it’s been more than 30 years since the McMartin trial ended, Chapman says his story is just as relevant today as it would’ve been in the ’80s. He points to QAnon and other bizarre disinformation campaigns as proof that we’re still susceptible to the baseless fearmongering that fueled the Satanic Panic.

“Fear is contagious,” he says. “It spreads exponentially faster now, thanks to social media. Titling this novel after a kids’ game was a conscious effort on my part to focus on the notion that we are spreading fear at such a devastating rate that there doesn’t appear to be any salvation in sight. Disinformation. Rumors. Hate speech… It all feeds into our fear. But what are we even afraid of? A Satan-worshipping cult of Democrats sacrificing children in the basement of a pizza parlor? How did a fiction like this ossify itself into fact for some people? How could they believe Pizzagate is true?… It’s belief, our conviction that these stories were true, that fueled the Satanic Panic era. And now technology has brought it into our modern mindset, essentially pimping our paranoia’s ride, if you will.”

Like most horror writers, Chapman tapped into his own fears and experiences for his novel—particularly that unique terror that comes with parenthood. Chapman is the father of two young boys, and he says he needed to become a dad before he could write this story. He essentially cast himself in both of his novel’s main roles.

“My childhood became the fear-fodder for Sean’s narrative,” he says, “while, as a relatively recently inducted father, I was able to take the terror I tend to experience on a daily basis and exploit it to the high heavens.”

Chapman has been mining his own fears as a published writer for more than 20 years. (He’s also a produced screenwriter, playwright, actor, and comic book writer.) He signed a six-figure publishing contract before he even graduated from college. Two books came from that deal: a 2002 short story collection titled Rest Area and a novel called Miss Corpus two years later. While the books were well received by critics, neither caught on with readers.

“It was only when nobody bought those first few books that I really fell on my ass and had to figure out what the hell I was doing,” he says. “I kind of went into publisher jail. Nobody wanted to publish my junk. That was the most painful part. The same people who had validated my writing before weren’t validating it anymore because it just wasn’t selling. ‘That’s just business’ was the common refrain I’d hear. And it killed me. Those were some dark, dark years.”

What Chapman did next, though, is what separates career writers from one-offs: he kept writing, and he tried different things. First came the Tribe trilogy, a series of middle grade novels published by Disney Hyperion. Those books weren’t commercial successes either, even though he considered himself fortunate to be able to tell the story he wanted to tell.

“Then—and only then—did the opportunity to write horror fiction for adults present itself,” Chapman says.

His relationship with Quirk Books began at a book fair, when Quirk’s Jhanteigh Kupihea mentioned to Chapman’s agent that she wanted to expand the house’s horror line. That conversation led to The Remaking, and then to WHISPER DOWN THE LANE.

“All I’ve ever wanted—ever dreamed about, really—is a house I can haunt,” Chapman says. “Quirk is that house. They have given me space to tell the stories I’ve wanted to tell. I recognize the rarity of that, and I truly owe it to my editor, Jhanteigh Kupihea. Quirk has put their faith in me. They believe in my stories, believe in me as a storyteller, and all I want to do is make them proud.”

Chapman is currently at work on a third horror title for Quirk. He can’t reveal any details at press time, only offering the most spectral of clues: “Just between you and me, it’s got ghosts in it.”