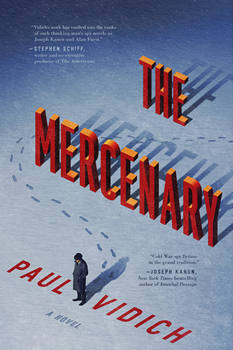

Up Close: Paul Vidich

Literary Work Disguised as a Spy Novel

By Karen Hugg

By Karen Hugg

While Paul Vidich has never been a spy himself, you’d never know it after reading his novel THE MERCENARY. His portrayal of Cold War relations between the US and USSR is impressive, to say the least.

The story follows retired CIA spy Alek Garin, who’s worked both for the CIA and KGB, on a mission to exfiltrate a KGB officer and his family from the Soviet Union. It’s never been successfully done before, and Garin, a complex soul raised in America by a Russian mother who was a spy, is unsure he can pull it off. But a dual heritage comes in handy when having to maneuver through a dangerous 1980s Moscow, a secretive city where eyes and ears are watching and listening everywhere.

This taut, mesmerizing thriller is the third of a collection set along the same timeline as Vidich’s An Honorable Man and The Good Assassin. Its winding plot, like any great spy novel, tugs you along while making you wonder who’s to be trusted and what will happen next. Plus, it has the intelligence and gray areas of a John le Carré novel. Of course, this isn’t a surprise since, as Vidich says, he greatly admires le Carré “for his ability to disguise his literary works as spy novels.” That kind of disguise works well in THE MERCENARY too.

Here, Vidich talks with The Big Thrill about the book’s origins, Cold War espionage, the Russian spirit, and how disinformation is a powerful tool in politics, especially today.

Did you find the idea for THE MERCENARY in a true story or was it solely a result of your imagination? What were its origins?

I came across the true story of the failed exfiltration of a Soviet intelligence officer while researching my novel. I had already decided to set the novel in Moscow near the end of the Soviet Union. I usually start with a novel’s setting. Setting isn’t just scenery or an illustrator’s eye for detail, but it’s all the things that draw a character to a place, establish atmosphere, and evoke the story’s imaginary world. I happened to read about Adolf Tolkachev, a Soviet military specialist and spy, who the CIA tried to get out of Moscow. I thought it a good premise.

I was fascinated by 1980s Moscow. The Soviet Union in the twilight of power struck me as a good place to set a Cold War novel. It was the moment when the country’s illusion of dominance met the grim reality of a crumbling system. I researched the 1980s Soviet Union for six months. I read several autobiographies of high-ranking KGB officers who successfully defected to the West. I was able to understand the hopes and fears of these men and women, and once I understood their world, I was able to let my imagination fill out a plot that emerged from the characters’ lives. It’s a messy process, and it required my willingness to be patient with the material. I created the characters by accessing my own emotions and psyche, combining them with real-life accounts of KGB officers, and scraping the material together into a mental space where they came to life. The premise of an exfiltration became the foundation for a larger story.

Across all of your books, you demonstrate a sharp, thorough knowledge of espionage practices, foreign cultures, and geopolitical landscapes. Yet you never worked as a spy or in the CIA. How did you educate yourself to make such a rich setting for your fiction?

I did not work for the CIA, nor have I been a spy, but I got to know the world of espionage through my uncle Frank Olson, a bio-weapons Army scientist who died in 1953 while working for the CIA. I discovered what it meant to work in a clandestine service. He was a man with grave doubts about biochemical weapons used in the Korean War, but the top-secret nature of his work prevented him from sharing his doubts with his wife (who knew nothing of what he did), and he couldn’t talk to his colleagues without appearing to be disloyal. He carried his burden alone. Olson’s moral quandary helped me create characters who risk bringing some of the darkness of their work into themselves.

The writer’s sleight of hand is to create the illusion of a world that comes to life through the eyes of its characters. Fear, paranoia, love, trust, and the host of emotions that make a compelling story come out of the characters themselves. Characters feel the fear or love that readers vicariously experience. I also did a great deal of research on Moscow: street names, traffic patterns, the things that a character walking on a street would see. All these details were important to establish authenticity, but they have to be transparent, and they have to be in service of the characters’ lives.

THE MERCENARY follows a man who is formed by both America and Russia. What drew you to this idea of dual cultural identities? Do you have any experience with it?

My father’s parents emigrated from a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that later became Yugoslavia and is now Slovenia. I first visited Yugoslavia as a ten-month-old child and have been back many times. A few years ago, I became a dual citizen: US and Slovenian. My mother’s relatives, on the other hand, arrived in America in 1632 aboard the Angel Gabriel, a 240-ton English passenger galleon. It was used to bring Puritans to America during the great migration.

From an early age, I was very aware of these two competing heritages. I experienced the tug between the different halves of myself and, somewhat unconsciously, that divided cultural identity found expression in Alek Garin, the novel’s protagonist.

When I wrote THE MERCENARY, I also had in mind the television series The Americans, written and executive-produced by an old college friend. This is the TV show in which a Soviet couple, the Jennings, live as normal Americans in Washington, spying on the side. In spy parlance, they are known as illegals. I was curious about their children, Paige and Henry, who were born in America, raised as Americans, and then shockingly discovered their parents weren’t who they said they were. My character Garin is the son of an illegal, as the Jennings’ children were, and he is torn between his Russian heart and his American head.

Vidich and his son, Arturo (also a writer), in the south of France during one of their many trips to Europe

I spent some time in St. Petersburg and found Russian people to be extraordinarily tough, yet many still had hearts of gold. I think you well captured their practical cynicism and a bit of their romantic wild spirit. Did you come across this in your research or from any personal experiences?

I encountered those uniquely Russian and Eastern European traits in the autobiographies of Soviet spies and by listening to my Eastern European friends, some of who are also writers. I was a fellow at the Sozopol Fiction Seminar in Bulgaria some years back, and I encountered wonderful Bulgarian writers (big men, physically) whose gruffness masked lack of confidence and whose practical cynicism covered up a kind of sadness. One incident in particular was revealing.

Alex Miller, a wonderful Australian writer and our workshop leader, presented a surprise exercise to our combined group of American and Bulgarian writers. He asked each of us to say why we wrote. Alex cautioned that glib answers were just that, transparent cover-ups, and honest answers were difficult, but we were writers after all, and we had an obligation to tell the truth, whatever that was. When Alex turned to me, I spoke from an unrehearsed and vulnerable place. Emotion welled in me, startling me. I struggled to stay articulate while weeping about my parents’ divorce when I was a child. It didn’t matter that the facts in question were 40 years past. When I finished, the mood in the room had changed. I watched with interest as the next up, my Bulgarian colleagues, all men, all accustomed to protective cloaks, opened up one by one. One Bulgarian talked about a son who had recently died. Everyone was quiet and attentive. I saw who these men really were, and it stayed with me until I found a way to incorporate some of that into THE MERCENARY.

I know little about espionage but as I read THE MERCENARY, I learned much about how spies use information and disinformation to a complex advantage. We try to mislead our enemies, and they try to mislead us. I can’t help but ask if you have any insights on that in light of the last (Trump) administration?

Disinformation has long been a tool used by the Russians (and the Soviets before them), as well as the CIA. Kompromat, the Russian word for materials collected specifically for blackmail, has broadened in meaning to include disinformation spread for advantage. The tool has become more insidious, and harder to defend against, as communication has broadened with the internet and social media has decentralized news. Influencers and the influenced are the new front line of hostile engagement with Russia.

The CIA has been concerned with America’s vulnerability to Soviet disinformation since its formation in 1948. Richard Helms, who later became Director of Central Intelligence, went before Congress in 1961 and offered 32 examples of dangerous disinformation perpetrated by the Soviet Union. In 1977, Dr. Sidney Gottlieb, head of the CIA Technical Services Division and head of the agency’s MKULTRA program, testified before the Senate that there was concern that the Soviets had sequestered members of the presidential party traveling overseas, and administered mind-altering hallucinogens. This was the Manchurian Candidate scenario, applied not to the president, but to the members of his staff traveling with him.

Let’s turn to the Trump administration and the case of Michael Flynn. “Blackmail Target” was the phrase cited by the Department of Justice when it offered the White House evidence contradicting National Security Advisor Michael Flynn’s denials about the nature of his conversations with his Russian security counterparts. Flynn, as we all know, resigned. Flynn’s lie about his conversation opened the possibility that he, unwittingly, was an agent of disinformation.

It would work this way. A Russian diplomat in a cocktail conversation with an American counterpart (think Flynn) inadvertently drops a causal comment on an important topic, having been directed to do so by Moscow Center, and the American, intrigued by the comment he isn’t supposed to have heard, makes note, and he becomes an unwitting messenger of misinformation to the White House. A similar comment is made by another Russian diplomat at another cocktail conversation 1,000 miles away and reported by a second American, so when the two connect in the White House they seem to confirm each other. This planted disinformation is subtle, its chance nature enhancing its likely truth, and it operates inside the White House to manipulate presidential thinking. Flynn would not have to have been blackmailed to have posed an intelligence threat. He simply would have to be careless and ambitious—traits that by all reports he has in abundance. The chances of success are increased if the president himself, in this case Trump, was inclined to trust the Russians.

The main character, Alek Garin, has a kind of logical stoicism to his personality. Do you think being a spy requires being stoic and logical?

Covert CIA officers (spies in the popular imagination) are highly trained to work in hostile conditions, live double lives, and be alert to danger. This requires preparedness. What appears to be stoicism may be studied vigilance, and what appears to be logical thinking may be conditioning. The spy who finds herself being tailed knows that she should continue walking on without letting the tail know she knows she’s being followed. That is what her training has taught her. Stoicism and logical thinking are defenses against unpredictable circumstances.

Many wonderful autobiographies of former CIA officers illuminate the psyche of the successful spy. These books often are more interesting than spy novels. William Hood, an author and former CIA officer, said that if you peel away the claptrap of espionage, the spy’s job is to betray trust. To do that convincingly requires intelligence, a bit of bravado, and a belief in the moral worth of your cause, and, yes, some decent training. The best spy is the one who no one identifies as a spy. The story goes that William Colby, a covert officer and then director of Central Intelligence, the nation’s top spy, mastered the look of being unseen. He was the bland character in an ordinary suit and tie, with clear plastic glasses, who could walk into a restaurant without catching the waiter’s eye.

Along those lines, why did you choose to write spy novels in particular? And not stories related to your earlier career in music and entertainment? Were spy novels the kind of books you’d always liked?

I write the type of novels that I like to read. From an early age I was drawn to the literary work of Graham Greene and John le Carré, and later to Alan Furst, Joseph Kanon, Eric Ambler, Olen Steinhauer, and others. I suppose it was always in me to write spy novels.

I quickly discovered that spies are ideal subjects for fiction. They are people who lie for a living. We all lie a little in our lives, but the spy’s life is all about deception and betrayal, and usually it is done for idealistic reasons. John le Carré once said that a spy story is not just a spy story, but it can be a love story, a story about engagement and escape, and about the search for integrity. But it is also a spy story. Spies marry, cheat, divorce, play games of sexual and political betrayal, and all that operates with high stakes, which makes the novel entertaining. Spies lie in the service of truth, suborn friends in the name of national security, and conduct extrajudicial assassinations in the name of justice. We are fascinated by these contradictions and are entertained by the inherent hypocrisy.

I found a lot of John le Carré in your style. What did his books teach you? How did he inspire you?

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, le Carré’s third novel, had a hypnotic effect on me when I read it in my twenties. Published in 1963, it captured the dark Cold War zeitgeist that followed the erection of the Berlin Wall in 1961. It was a world so real, so true, so compelling that it stayed with me long after I closed the book’s covers. The grim story, its empathetic characters, the clever plot, and the masterful writing changed my way of looking at spy novels. I have read and reread the book to figure out how he pulled it off.

When I was writing my first novel, An Honorable Man, I struggled to find a voice for my main character, George Mueller. The book, inspired by the case of my uncle, Frank Olson, who was murdered while working for the CIA, explores the dark side of Cold War spying. I found the right voice by listening to the voices in le Carré’s work. After le Carré’s death two months ago, I looked again at THE MERCENARY, and I realized that it is, quite unconsciously, a homage to the Leamus character in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

Do you have a new project in the works? What’s next for you?

My next book is set in Berlin in 1989, as the Berlin Wall falls. It is titled The Matchmaker.

- Debut Spotlight: Roxana Arama - January 31, 2023

- International Thrills: Claire Douglas - August 1, 2022

- Up Close: Timothy David Mack - March 31, 2022