A Fascination with Memory

By Dawn Ius

By Dawn Ius

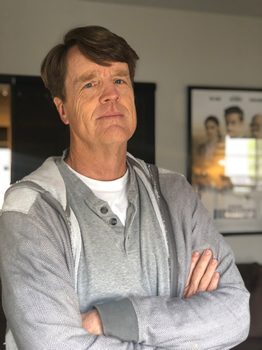

Daniel Pyne is fascinated with the nature of memory—its reliability, its limitations and opportunities. How it grounds or defines us.

It is this fascination, in part, that led to the creation of Aubrey Sentro, a black ops specialist one concussion away from death—and the fierce protagonist of Pyne’s new series, which kicks off with this month’s WATER MEMORY.

Aubrey may not have the sharpest brain these days, but when pirates hijack the cargo ship she’s on, her training takes over. Avoiding or killing her potential captors seems easier than the more pressing issue she faces—her memory lapses are becoming more frequent, and she soon realizes her only chance of survival is to not forget. She trains her mind on her children—because if her memories make her vulnerable, then motherhood makes her downright dangerous.

In his first-ever interview with The Big Thrill, Pyne—an accomplished screenwriter and the co-showrunner of Bosch—shares insight into the genesis of his new series, the startling “ripped from the headlines” facts that inspired WATER MEMORY, and what he envisions for his protagonist in upcoming installments.

WATER MEMORY kicks off a new series for you—congratulations! What can you tell us about the series’s genesis?

I actually hadn’t thought it would be a series; I’ve never done one before. The inspiration was a combination of character and setting. I had wanted to write a story about a woman doing what is culturally considered to be a man’s job, and explore how that might affect her relationships, the way she approaches the job, her doubts and fears. In the movie business, we’re often separated from our families for extended periods of time, and I’ve observed how different people deal with it, and how men and women deal with it differently, and how it affects the children. I’ve always explored gender roles in my work—the protagonist of Pacific Heights is a woman, a couple of my TV series have had a strong female lead in the ensemble, the character of Eleanor Shaw in The Manchurian Candidate was re-imagined in a modern world, and arguably the strongest character in the movie. And then, on a tech scout with Tak Fujimoto, the great cinematographer, he told me about how he’d taken a cargo ship cruise before starting work, just to meditate and chill out. Coincidentally, I’d been doing research into maritime piracy—and the weird business that has cropped up around it, involving insurance companies and the middlemen who negotiate ransoms for relatively bloodless kidnappings. And I started thinking how interesting it would be if a black ops specialist happened to be onboard one of these ships when it got attacked. How, rather than simply being like “Die Hard on a boat,” there would be all kinds of hidden agendas being upset by this force of nature who, by temperament and training, would want to resolve the issue with the skills they had.

When I reached the end of the story, I realized there was still more to explore with Aubrey, both in her past and her present. She’s still a relatively young woman, with grown children who she’s deceived for years, and a shot at a new, different life from the one she’s lived. So another story began to emerge from this first one.

Aubrey is a fascinating protagonist—and admittedly, the kind that would usually be male in these kinds of books. What drew you to creating this female character, and as a male, did you find it hard to develop her?

All characters are hard to write well. I like to think that a good writer can put him or herself into almost any character’s head. Not to say there aren’t important cultural considerations to be acknowledged and respected. But Patricia Highsmith wrote some amazing novels with men at the center of them. Same with Katherine Anne Porter, Flannery O’Connor, Dorothy Hughes. For me it was a matter of writing to character rather than archetype; Aubrey is an individual, the product of a specific set of circumstances and life forces, not the flag-bearer of some larger social commentary about women, or men. I’ve been lucky to have a number of strong women in my life, and I tried to channel them a little bit for this. But I also stuck to common themes that I know well: courage, family, love, betrayal, self-doubt. I have two grown children, so I know how that sometimes goes. And I thought it might be interesting to blow up some of the tropes about the action genre with which, from my screenwriting career, I am granularly familiar. I tend to gravitate to stories about ordinary people who are faced with extraordinary circumstances. Aubrey is not so ordinary, but I wanted to ground her in the world I know, to imagine a thriller world in which evil has a familiar banality, weapons misfire, plans go awry, chaos is the organizing principle, and the primary goal is survival, of yourself and those you care about.

This story requires you to go deep in Aubrey’s mind—a mind that has been through tremendous trauma. How did you navigate that research and apply it to her character?

I was introduced to the concept of concussion syndrome while working on the script that became Any Given Sunday. There’s so much that’s still not known. But then, reading about the endless conflict in the Middle East, I stumbled across a number of stories about how exposure to IEDs and other concussive events was affecting soldiers who were not directly wounded in a battle. It made perfect sense that they would face the same risks that a football player might. Among the things that fascinated me about it was that, unlike dementia, the course of it was uncertain. I’m also blown away by how our mind can find workarounds, adapt to challenges, even rewire itself if it needs to. Some people suffer progressive symptoms, some don’t. It gave me a great deal of latitude to explore memory itself, which I’ve examined in other books and screenplays as well. I tend to be a scavenger of information—I sometimes just go down the rabbit hole on Wikipedia to see where I might wind up. And sooner or later, all the random facts and stories I’ve collected find their way into my writing, one way or another.

How much of WATER MEMORY is based on fact? Is there a thriving business around hijacked cargo cruises?

Yes there is. I don’t know how thriving it is, but there is a gray market that involves insurers, shipping companies, and middlemen who have turned hijacking into a market economy in which it’s often easier for the shipping company to just pay the ransom than to try and seize the boat back. I was amazed at how, even today, with all our sophisticated tracking and high-speed travel, trying to find a single cargo ship in the ocean is still a challenge. Add in questions of jurisdiction, the position of most countries that they will not negotiate with kidnappers or terrorists. . . the free market can find the potential for profit in anything.

WATER MEMORY reads like a movie—which is probably not shocking given your screenwriting background. What led you to novel writing? Is there a medium you prefer?

I wish it read less like a movie, but I’ll take that for a compliment, I guess. I initially set out to be a prose writer and, discovering that I wasn’t getting anywhere doing it, kind of fell into screenwriting and realized that it was a career of its own. I do love movies, and I’ve always written visually. I don’t prefer one over the other; I find them each challenging in its own way. Telling a story with pictures is extraordinarily dynamic, and finding ways to show what your character is thinking through his or her behavior, movement, reactions is almost poetic. But the business of filmmaking is grueling, oftentimes demoralizing—the endless notes and judgment can cause you to avoid exploring creative notions that you are sure will get shot down in a room, or a meeting. They don’t call it “show business” for nothing. Writing novels has been more peaceful for me. Very rewarding, even if nobody reads them. I love writing, putting words together, finding new ways to express things. But at the end of the day, films or novels, or television, it’s all about the storytelling, and the characters. I approach them the same way. The difference is just in the lens I use to tell it.

I read a great post you wrote on “Things Learned as a Moviemaker.” What would you include on a list of things you’ve learned as a novelist?

I’ve learned to be a more patient writer. Screenplays are a burst of inspiration; you tend to be able to hold the entire shape of the story in your head, and because they move relentlessly in one direction, you tend to avoid anything that will impede the momentum. As a novelist, I think I’ve gotten more skilled at letting the story go where it wants, even if it means a side trip or digression that appears not to have a pay-off.

What lessons from screenwriting do you apply to your novel writing, and vice versa?

I like that I had to learn concision as a screenwriter, and that I try to make every word matter. I also think that my books have a consistent geography, because when you’re writing movies and television, you have to be always aware that your characters are operating in a real space, in real time. Sometimes the location defines the action—I think sometimes a trap in novels is thinking that you can imagine the space your character needs in order to do what you want them to do (or that they want to do), and it’s much better when the reality of a place creates another obstacle to the goal. I’m not sure that I’m bringing much back from my novels to my screenwriting, but maybe that’s just because I’ve been doing more screenwriting, longer.

What can you share about the second book in this series?

It’s not on a boat. It’s both a prequel and a sequel; examining the botched Berlin operation that Aubrey was involved in at the beginning of her career, and the inevitable consequences of it, which begin playing out in her present-day retirement. Her daughter Jenny has a big role in the second book. Some fraught mother-daughter stuff, as they attempt to reconcile how Aubrey’s work has affected both of them.

Do you have any additional projects—TV shows, movies, books—that you’d like to tell our readers about?

I have another novel almost finished, about two young CIA agents who were shot down and captured by the Chinese during the Korean War and spent the next 20 years in prison. It’s inspired by a true story. There’s a couple of TV projects I’m trying to get off the ground.

You note on your website that you have a healthy collection of TV pilots that didn’t get made. Rejection, unfortunately, is a reality of this business. What advice would you give to aspiring writers who are facing some of the toughest obstacles in terms of getting their work produced/published?

You have to focus on the things you can control. There’s your art, and there’s the business. You can’t control the business. You can only hope that something you create will intersect with what the business wants, or needs. And even if it does, most writers and filmmakers suffer way more rejection than they do success. And let’s not even talk about the critics who, thanks to the internet, are now pretty much. . . anyone with a keyboard.

You have to really want to do this. And I think you have to do what you want to do, not try to chase what you think the audience or reader wants.