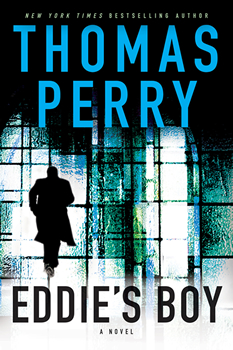

Eddie’s Boy by Thomas Perry

By Karen Hugg

By Karen Hugg

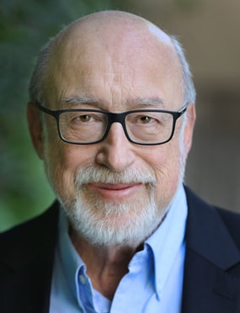

Though Eddie the Butcher is a fictional creation of Thomas Perry’s mind, the author is no stranger to mob activities. Growing up in Tonawanda, New York, Perry remembers times when suspected mobsters were shot and dumped near creeks and in deserted areas of western New York. He remembers the don of Buffalo, Vincent Maggadino, and the funeral home he had in Niagara Falls. He even remembers a field that he and his childhood friends played in that once served as a dumping ground for a mutilated body.

Over the years, Perry has deftly woven these experiences into an exciting series of novels featuring a character he calls the Butcher’s Boy. In his latest installment, EDDIE’S BOY, the once boy is now a man in his 60s, living a comfortable life with his wife in England. But an attempt on his life sucks him into the underworld he thought he’d left behind, forcing him to find and kill his assassins before they kill him first.

Perry, the author of 28 novels, holds a Ph.D. from the University of Rochester and has won the Edgar Award but knows the humble jobs of mechanic, factory worker, and commercial fisherman. This wide swath of experience has given him the vision to create such memorable fiction as the Jane Whitefield series, the Butcher’s Boy series, and standalone novels like The Old Man, Death Benefits, Night Life, and Pursuit, which won a Gumshoe Award in 2002.

In this interview with The Big Thrill, Perry talks about the Butcher’s Boy series, his work in television, and his novel writing process.

In several of your wonderful books, you’ve written about people with dark pasts disappearing from society’s radar. In some cases, they’re dragged back into dangerous situations they’ve worked hard to avoid. What draws you to these types of scenarios and these kinds of people?

I’m interested in writing about the best qualities that people have—things like personal courage, self-sacrifice, loyalty, and ingenuity. In order to test the characters and force them to find these qualities in themselves, I put them in extreme situations, usually in potentially fatal trouble. The idea of having to run and hide from pursuers has a primal, fundamental scariness to me. And being a fugitive who isn’t exactly innocent means the character can’t call the police or any other authority for help.

In EDDIE’S BOY, we find the man now known as Michael Shaeffer getting tangled up again in the mob underworld. It’s been interesting to see his character age. What made Michael compelling for you again at this time of his life?

I’ve actually been drawn to him at four times in his life. The four installments of his story, The Butcher’s Boy, Sleeping Dogs, The Informant, and EDDIE’S BOY were written in roughly 1979, 1989, 2009, and 2019. My mistake was to make him my age in the first book, so that when I was 10 years older, I noticed changes in myself, and wondered how he would be 10 years later. I concocted a new set of threats and challenges, and unleashed them on him in Sleeping Dogs. The Informant came from a discussion I had with one of my agents. She asked me to write a description of what Michael would be doing 20 years on. I wrote the description of The Informant and decided it might make a good book, so I wrote it.

EDDIE’S BOY is actually the most ambitious book of the series, because it’s both a thriller set in the present about an old retired killer fighting deadly enemies, and a search of his own memory of how and why he acquired the skills and bits of wisdom that are keeping him alive right now. In a way the four books together are the two kinds of time-travel that are real—slowly living through 40 years of life, and being able to look back from the end of 40 years and reassess the events along the way.

Michael’s character deepens nicely with the flashbacks to his time as a teenage boy. What personal experiences did you draw on for those?

I grew up in a time and region of the country in which the Mafia was not a theoretical entity. In my elementary and junior high years, there was a war going on between factions. Two boys I knew found the mutilated body of a man who’d been dumped in a field where my friends and I played. There were men and businesses that people knew or suspected were mob-connected. It was probably inevitable that when I was grown up and looking for a frightening and powerful set of adversaries for a book, La Cosa Nostra would be a candidate.

In some ways, EDDIE’S BOY is a hit man procedural. We learn so much about how to move about, break into homes, and kill without being tracked. What sources did you use to learn these seemingly realistic, clever tricks?

I’ve noticed that when you begin to write about a particular criminal activity, the details that come to light stick in your mind. Reading a newspaper account of a crime brings many details about how the crime was committed, detected, and punished. If you write about crime, people begin to share stories about crimes they’ve committed or suffered from or solved. And just from owning and maintaining a car and a house you notice things about doors, windows, locks, and alarm systems that would enable you to break in. Most people give little attention to these bits of information. A person planning a killing—real or fictional—does not. In a way, the killer and the writer are in the same profession.

Michael Shaeffer and Elizabeth Waring’s trajectories unfold in a kind of parallel across all of the books. Can you talk about your choice to hop back and forth between his and her perspectives?

Elizabeth is the smart, non-criminal observer who seeks the truth. In the first book, Elizabeth is 22 years old and one of the lowliest beginners in the Justice Department’s Organized Crime Task Force, as it was called then, looking for bits of information on old-fashioned computer printouts that might indicate a death is organized crime-related. As the story goes on, she is the only one who sees the various scenes in which the Butcher’s Boy left someone dead and realizes that none of her superiors’ plausible interpretations of the evidence is ever right. She’s the only one who really discovers what’s going on. In a way, she’s the book’s reader.

In the second novel, 10 years later, she has married the FBI agent she was working with in the first, had two kids with him, and lost him to cancer. She’s a bit higher up in the department, and is again the only law-enforcement mind that sees clearly. The Butcher’s Boy meets her, and ultimately gets out of the country to safety only by stealing her late husband’s passport during a visit to her house. Ten years after that, in The Informant, she is high in the Justice Department hierarchy. She and Shaeffer make an arrangement in which he tells her where to get evidence on a murder that occurred years ago, and in exchange, she fills him in on what’s going on in the Mafia right then. Each is serving as the other’s informant, but each is trying to fool the other. In EDDIE’S BOY, she is still trying to capture him and keep him in jail for life as a source of information. He is trying to get her to unwittingly tell him who he must kill to save himself. But when she’s with her colleagues, Elizabeth is always the smartest person in the room.

Will you ever reveal Michael Shaeffer’s given name?

I don’t intend to, but anything is possible. Since I only seem to write one of these books every 10 years, whether I’ll even get the chance is a question for the life insurance actuaries.

Being a crime writer who likes to put plants in stories, I have to ask you about the use of cowbane in Poison Flower. I love that Jane Whitefield carries a natural poison made from it, which enables her to commit suicide in case she’s cornered into revealing the people she helps. The plant’s been used for centuries as a deadly weapon. Where did you discover this useful idea?

During the period when I was writing the first few Jane Whitefield books I happened to read in a book about her ancestors that when an old-time Seneca wanted to commit suicide he would chew and swallow a couple of bites of the root of cicuta maculata, the water hemlock, which is the most powerful plant poison that grows in North America. It’s not at all painless, but it’s quick and sure. The plant grows plentifully all over the Northeast, and its common name, cowbane, is well-deserved.

For Jane’s use it had to be portable and unrecognizable, so I have her mash the roots for the juice containing the neurotoxin and concentrate it so she can carry it in a perfume bottle in her purse. I’m glad you use plants in your stories. They’re such a big and ever-present part of the real world that I miss them when they’re not in a story.

You spent some time writing for television. It seems in television a writer can try out more ideas and move on more quickly. They don’t need to write an entire novel (or even the first three chapters) to get a greenlight on a project. What are the pros and cons of writing for television versus writing novels?

When you write a novel, you are the only person who has a say about what you write or how you write it. You are dependent entirely on your own knowledge and imagination, and you don’t have to even tell anybody what you’re doing until you’re ready to sell it.

Writing for television is more lucrative than writing books, but television is always a collaborative medium. My wife, Jo, and I wrote as partners on the staffs of several prime time network television shows for about a decade. We made some good friends, learned some lessons about writing, and never regretted doing it. But part of what you’re selling to the studio is your freedom. The executive producer, the studio, and the network are all there to control a show and make sure that it’s a success, and they all have big money and careers riding on succeeding. Your job is to help. That usually requires many more hours a week than 40. Jo and I ultimately stopped working at it full time because our first baby was about to be born, and we wanted to be able to raise our children with the kind of attention our parents devoted to us.

Your book The Old Man is now being produced as a TV series. It will be interesting to see Jeff Bridges in the lead role. Did you draw on your script-writing skills and contribute to the scripts at all? Did you have a hand in casting it? How did the process work?

While I’m eager to see the series, I had absolutely no hand in making it. I visited the set twice at the invitation of the kind and talented people who were doing the work, and I was impressed by the way the scenes they shot were done. Then I got out of their way and went home to get back to the book I was writing.

For fellow thriller writers, how do you approach writing a thriller? Do you plot an outline first? Create based on an image or bit of dialogue?

Shortly after I email a finished manuscript to my editor, I sit down in front of a blank piece of white paper, pick up a pen, and begin to write the next story. Sometimes I start with an observation or a description of something I’ve seen or imagined, a piece of dialogue, or a motion. That first page may end up surviving the process and remain the first page of the novel, or appear later in the book, or be crossed out, but it gets me started on telling a reader a story. This way I’m usually only out of work for an hour or two a year.

What are your favorite thrillers written by women?

This is an interesting question, because I’m a firm believer that what’s on the page matters, and it’s the only thing that does. There are some wonderful writers of crime fiction active right now, some of them women—Meg Gardiner, Laura Lippmann, Laurie King, Dana Stabenow, Val McDermid, and Lisa Brackmann come to mind. I have to add my wife, Jo Perry. Her four Charlie and Rose books, Dead is Better, Dead is Best, Dead is Good, Dead is Beautiful, and her novella Everything Happens, are certainly my favorites by a woman crime writer—not out of loyalty to my one-time TV writing partner, but for their combination of philosophical profundity and playfulness, irony, humor, originality, pace, and humanity.

What’s on the horizon for you? Any new books or other television adaptations in the works?

I’m always working on a book, and I hope to have the current one finished soon. I’m not ready to talk about it yet, because I find that once I’ve done that, it feels as though the story has been told, and I’m not as eager to get back to it. There are a couple of other books I’ve written that are under option for TV series or movies, but what becomes of them will not be up to me.

*****

Thomas Perry is the bestselling author of twenty-eight novels, including the critically acclaimed Jane Whitefield series and The Butcher’s Boy.

To learn more about the author and his work, please visit his website.

- Debut Spotlight: Roxana Arama - January 31, 2023

- International Thrills: Claire Douglas - August 1, 2022

- Up Close: Timothy David Mack - March 31, 2022