Up Close: Sam J. Miller

Constant Obsessions

The best horror is always timely, but this year’s standout offerings, from Paul Tremblay’s virus epic Survivor Song to Jeremy Robert Johnson’s class-warfare battle cry The Loop, have felt disturbingly prescient. With a pandemic and a historically divisive election amplifying anxieties they would have been exploring anyway, the last few months seem to have turned horror writers into clairvoyants.

Enter Sam J. Miller’s THE BLADE BETWEEN, a supernatural thriller that hinges on an eviction crisis. Miller’s novel, which also touches on homophobia, income inequality, and America’s refusal to come to terms with its history, feels like the most 2020 novel imaginable, even though Miller could’ve written more or less the same book 10 years ago.

“The things I was writing about in THE BLADE BETWEEN are things that I have spent years and years obsessing over and things that are fundamental to how America works,” says Miller, who spent 15 years working as a community organizer for the New York-based nonprofit Picture the Homeless. “Developers never want to create housing for poor people, and there’s no situation where that’s suddenly going to become a priority until and unless people get together and really organize and demand it. So I can’t imagine that there would have been too much different if I had written this book now versus 10 years ago versus 10 years from now. This particular face of the ugliness will look a little different, but I think the fundamental ugliness will be the same.”

THE BLADE BETWEEN is set in Miller’s hometown of Hudson, New York, a port city that suffered a sharp economic decline in the second half of the 20th century, only to see a recent revival that has earned it nicknames like “the Un-Hamptons” and “Brooklyn North.” The book opens with New York City-based photographer and Hudson native Ronan Szepessy arriving in his hometown with no memory of why he came. He means to spend the night and return to the city, but instead he reconnects with a pair of old friends: his first love, Dom, and Dom’s wife, Attalah. The reunion proves fateful when Ronan and Attalah conspire to turn the tables on Hudson’s hipster invaders and save their friends from a wave of evictions brought on by rising property values, only to unleash a supernatural force that threatens to consume them all. Ronan, a gay man who fled Hudson after enduring years of homophobic taunts, slurs, and even physical attacks, finds himself defending some of the very people who tormented him so relentlessly.

“I think Ronan, like myself, has a really ambivalent relationship to the town he grew up in,” Miller says. “In ways he hates it, but he also recognizes that there’s much of value there, and that it’s a beautiful, historic place with lots of really good people, even if there’s also a lot of people who make him miserable. And some of those are good people too.”

THE BLADE BETWEEN has plenty of elements that would tag it as a horror story—there are ghosts, demonic entities, masked killers, and bursts of grisly violence that echo Hudson’s history as a town built on the wholesale slaughter of whales—but it has the skeleton of a traditional thriller. It’s a melding of genres that will be familiar to fans of Miller’s work, which includes his Nebula Award-winning YA debut The Art of Starving and the Shirley Jackson Award-winning short story “57 Reasons for the Slate Quarry Suicides.”

In his first interview with The Big Thrill, Miller explains the inspiration for his latest novel, talks about writing (and reading) diverse horror, and finally says out loud what we’ve all wondered: what if Friends is really an interdimensional plot to kill us all?

You’ve said that you most enjoy reading and writing about things that scare you. What fears are you exploring in THE BLADE BETWEEN?

I spent 15 years as a community organizer in New York City, working on issues of housing and homelessness, and specifically working with homeless folks. There’s lots to be afraid of in the world, but the brutal mechanics of the housing market, and how, in a capitalist system, nonviolent drug use is a crime but kicking a family out in the middle of winter is not a crime—I just think that speaks so deeply to the fundamental injustices of the housing market, and how this system deems people worthy or not worthy of decent lives. And so for me, it’s the fear of myself or my loved ones being displaced, being thrown out, and having communities destroyed.

The idea of a sort of bare, brutal drive for money slowly eroding everything we care about, is something that I obsess a lot about in New York City. I’m sure this is true everywhere, but in New York it feels particularly acute. Being a New Yorker means having everything you love slowly stripped away from you. You go to a neighborhood you haven’t been to in a while, and you see that this restaurant you love has closed, or you hear that this bookstore is gonna shut down. A lot of the things that I care about, like independent bookstores, and Polish dumpling restaurants and Tibetan restaurants, and weird, quirky stores that sell weird, quirky things—they don’t make a lot of money. And if you don’t make a lot of money, and you’re in the city, it’s really hard to survive. So that’s sort of the fear that is at the root of this—of people being made homeless, of communities being destroyed, of money coming along and claiming something and not caring how the humans caught up in the net feel about it.

I kept thinking about the story’s parallels to our history: Europeans came in and took everything hundreds of years ago, and now we’re seeing another crisis of displacement. Only this time, instead of Europeans displacing Native Americans and First Nations people, it’s the wealthy or privileged displacing the impoverished. It’s just this awful cycle.

Yeah, and we don’t learn from history because we don’t learn history. We don’t really learn its lessons, and we don’t really understand what has happened. The education that I got in a public school in upstate New York didn’t tell me anything that I needed to know about where our country’s wealth and power came from—that slave labor and stolen land were the root of America’s rise to global power. Even in our 20th century story of bringing down democratically elected governments because they were unfriendly to our business interests—if we don’t learn that the mechanism at the heart of America’s prosperity and power is consumption, and consumption is inherently exploitative and extractive, we’re going to keep feeding into that machine and then be surprised when it when it takes away everything we love.

THE BLADE BETWEEN is obviously a story that’s been cooking for a long time, and it features a character who first appeared in your 2016 short story “Angel, Monster, Man” (which I highly recommend to anyone who hasn’t read it yet). What’s the relationship between your short fiction and your novels?

There’s definitely a set of constant obsessions and fascinations that I keep coming back to. Whales were at the heart of my novel Blackfish City, and there’s a lot of importance of whales [in THE BLADE BETWEEN], because I think whales are amazing. And there’s a lesson of history to learn from the whaling industry—the idea that this beautiful, amazing, intelligent creature was a resource to be plundered for centuries, and that the only reason it stopped was not because we cared about whales, but because petroleum and other energy sources ended up becoming cheaper.

So there’s definitely a lot of obsessions that I revisit. And I do think of all of my work as taking place in a shared universe, so there’s lots of little cameos. That’s something Stephen King does a lot, where you’ll have a character mentioned who’s the older brother of the main character of this other thing, or the Deadlights in It get mentioned in Insomnia—lots of little things like that. As a reader, I love that, and being able to do that for anyone who bothers to read more than one of my things is a fun writer project.

Writers really love being asked where they get their ideas, so where’d you get this one?

There was definitely one moment where I came home to visit my family and I was driving around town, and I was stopped at a red light, and I just had this intense moment of anger and frustration at the way my town has changed, and the ways that people who’ve lived there for generations don’t always benefit from it and are displaced. And so that was sort of an epiphany—like, Oh, I didn’t know I had this rage, this anger, and maybe that’s something I need to explore. I originally started off writing a short story about it, but then it just got bigger and bigger and demanded to be a novel.

Do you consider it a horror novel? It’s being billed as a “supernatural thriller”; is that purely a marketing decision, or do you see a distinct line between that and horror?

I will say, first off, that I am really bad at genre. I love and read tons of genres. I read crime novels and detective stories and historical fiction and literary fiction and horror and science fiction and fantasy, and I write in many of those genres, because I really love those stories and the different sets of tropes you can play with. My first pro sale was a story called “57 Reasons for the Slate Quarry Suicides,” which I thought was a science fiction story, and I sent it to a science fiction magazine. It was my luck that the editor [John Joseph Adams, of Lightspeed and Nightmare magazines] happens to also have a horror magazine because he was like, “I love the story, but it’s not science fiction. It’s horror.” And I was like, “Okay, sure, do whatever.” And I ended up winning an award for horror for it. [The 2013 Shirley Jackson Award for Short Fiction]

So I clearly don’t know what the hell I’m talking about when it comes to genre. I tend to just write and see what happens. And if it turns out that what I’m writing is this genre versus that one, then that’s when, in the revision process, it really helps me to have an editor who can help me home in on what’s amazing about those genres. My editor for this book was Zach Wagman at Ecco, who’s now at Flatiron. He edits Dennis Lehane, and he’s edited a ton of amazing thrillers, so he has an incredibly good ear and eye for the genre. So I feel like I might have written this as a ghost story and then edited it as a thriller. It’s all over the place. That’s just my clumsiness or my grace, depending on how you want to look at it.

And yes, there’s a huge marketing factor. I think that publishing still has a vestigial anxiety about the word “horror.” There are cycles of boom and bust with horror, and for years and years, when I was a younger writer, I would hear “don’t use the word ‘horror’” or “horror books don’t sell.” So I think that what it’s marketed as is less important than what people enjoy it as.

Your work is offbeat and literary, but it’s also accessible and entertaining, all at the same time. When you’re writing a story or novel, do you give any thought to whether it’s going to have mainstream appeal?

I think I try. I always want to explore how I can reach new audiences and speak to new folks. But I think it goes back to me being bad at genre. Anytime I try to fit into a box, I’m probably going to do it badly. And so I think it’s natural that the scope of my reading is reflected in my work. I do read a lot of literary fiction—I’m not a genre writer who only reads in the genres that I write, and I think that really feeds my work and gives me ideas for theft. [Laughs.] I don’t know if you have this experience, but often when I’m reading a really great literary novel, with a really great plot, I’m like, “This is amazing. And it would be more amazing if it had werewolves.” So often I’ll be like, “Let me just steal this, but no one will recognize it because I’m going to add, you know, whale ghosts, or a floating city in the Arctic.”

So in terms of trying to be a bestseller or otherwise reach massive audiences, I think that I have long ago made peace with the fact that I’m writing really gay stuff, and while there are gay books that are bestsellers and have won huge awards, I think the default of what readers are looking for is still pretty shaped by a sort of hetero-centric storytelling model. So if I’m going to write about gay people and sex and addiction, eviction, displacement, racism, police brutality, all these things that are really important to me—these are not, unfortunately, things that are widely obsessed over, necessarily, and the communities of folks who do obsess over them are not the same audience for a more mainstream, beach-read bestseller. So I’ve made peace with not being a bestselling writer. If I become one, that’s amazing. But I want to write the stories I have the burning need inside to tell. That’s where I’m coming from, rather than any kind of exterior indicator of success. Or at least that’s what I tell myself.

People often talk about horror as an inherently conservative genre. Right now we’re seeing a renaissance of progressive horror—horror by and about Black people and LGBTQ+ people and Indigenous people and women and so on, and stories about the horror of being “othered” rather than the horror of the “other.” Does it feel like a better time to be a gay man writing horror than it might have been 10 or 20 years ago?

I’m not sure if it’s real, but it feels that way.

Some people who are horror fans have been unable to read a lot of horror this year, but I’ve been reading a lot of horror and I’m being constantly impressed and startled by how gay the history of horror is, in ways that even I, as a gay horror fan, didn’t realize. Like, I had never read Poppy Z. Brite—I tried when I was 13 or 14 and hadn’t come to terms with being gay, and the gay content made me so uncomfortable that I ran from it—and I had never read Michael McDowell. There’s just so many great gay and queer and LGBTQ+ horror writers. And that also goes for writers of color, like Tananarive Due. The history of horror is much more diverse than the mainstream thinks it is. But yes, it does feel like we’re in an amazing moment where folks from diverse and marginalized communities are telling their stories. And that’s across many different genres, and that is super exciting.

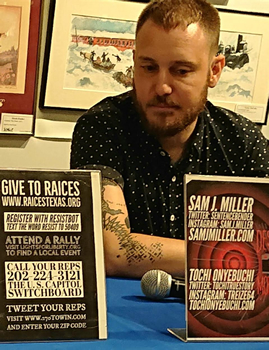

Miller at the launch of his third novel, 2019’s Destroy All Monsters. Photo credit: Juancy Rodriguez.

I also think we’re seeing a moment of reckoning in terms of some of the things that connect to why a lot of people hate horror, like lurid, graphic representations of violence against women or sexual assault. I think we’re in a place where I can now read a horror novel with a lot more confidence that I’m not going to stumble upon that and have to stop reading.

And I think part of the reason why horror has always been a conservative genre is because of who’s telling it. Not that those writers are conservative, but if your victims are White, straight people, then that’s going to shape who the monster is, and who and what victory looks like. And so there’s certainly a long history of horror where villains and monsters have been coded as queer in one way or another. Now there are a lot of writers challenging that.

Can you tell me anything about what you’re working on now or what might be next for you?

I’m working on a graphic novel pitch about a deeply troubled, gay relationship between two guys who are addicted to a futuristic drug that allows users to enter a shared hallucination. And also, I have this sort of recurrent thing in my fiction where I often explore the deeper cultural meanings of works of fiction, which is a fancy way of saying I write fanfic. I wrote a short story called “Things with Beards,” which is about The Thing, the 1982 film, and sort of what happens after. What if McCready was a gay man who was passing? And what if he has been replaced by a thing and doesn’t realize it and goes back to New York City? I’ve written a couple stories like that. I wrote a story about New York City six years after King Kong fell from the Empire State Building, in a world where that’s real. Now I’m thinking about a bunch of my pop-cultural obsessions. Like, what if Friends was a transdimensional, genocidal incursion?

I would read that.

So, yeah, that’s a short story that I’m about to write. And I’ve always been deeply unsettled by Goofy, and so Goofy-as-an-eldritch-abomination is another thing I’m sketching out. I’m saying these out loud, in part because it’s true and in part as accountability for me to put it out into the universe and be like, well, now I have to write this story about how Friends is part of a malevolent scheme from another dimension.

This talk is helping me understand why I enjoy and respond to your fiction so much. Please write all those stories.

I’m gonna try.

- The Ballad of the Great Value Boys by Ken Harris - February 15, 2025

- Don’t Look Down by Matthew Becker - February 15, 2025

- The Wolf Tree by Laura McCluskey - February 14, 2025