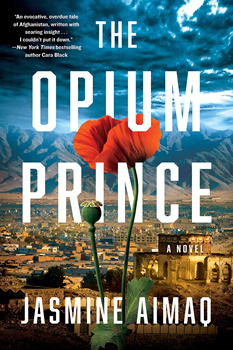

A Man and a Nation on the Brink

“My father used to tell me, The rich world has rules and regulations. The poor world has rituals and traditions. These worlds weigh the same.”

The speaker is Daniel Sajadi, whose father was an Afghan war hero, and in Jasmine Aimaq’s THE OPIUM PRINCE, he is about to find out the truth of those words the hard way.

It is 1977 Afghanistan, and Sajadi, half-American, half-Afghan, has just been appointed under questionable circumstances to direct a US initiative to destroy the country’s poppy fields when, in a distracted moment, he runs over a Kochi nomad girl and kills her. Fearing for his life, he turns to a sympathetic stranger named Taj Maleki, who helpfully intercedes—and turns one nightmare into another, much greater one.

Maleki is an opium khan, and he has a proposal: destroy the poppy fields, by all means—except his—and no one need ever know what happened to that girl. When Sajadi refuses, Maleki starts reappearing, at Sajadi’s office, at his home, insinuating himself into his circle, a man of charm “who could convince you not only that the emperor was clothed, but that you were the emperor.”

As he does so, the threats behind the charm become move overt, more specific, more horrible, and not only against Daniel: If Sajadi persists in leveling everybody’s fields, he says finally, he will kill every Kochi that was to have helped with the harvest: “Every man, every woman. Every child. Their lives are in your hands.”

As Daniel desperately searches for a way out, his marriage crumbling, his Washington bosses impatient, his days haunted by visions of the dead girl, the country around him unravels as well—the king deposed by a pro-Soviet coup, a religious crackdown giving birth to a fierce Islamic movement, armed demonstrations filling the streets. As for the poppy fields: “Blood was the greatest fertilizer of all.”

Aimaq has written a brilliant thriller filled with twists and turns and tragic miscalculations, a breathtaking story of a man pushed to the brink and a nation on the verge of violent revolution. The only difference is, our visions still haunt us today.

Photo credit: David Fournier

Aimaq is herself half-Afghan, half-Swedish, grew up in several countries, and has spent a lifetime in teaching and international non-profit endeavors.

“THE OPIUM PRINCE started brewing in my mind after 9/11. I was devastated by that day, as so many of us were, and felt a lot of anger and profound grief for the victims. I was teaching an International Relations class at USC and decided to make the Middle East a central theme to help my students understand the context around this horrific event. It became clear that most people did not know anything about the political history that spawned the Taliban, or the nightmare Afghanistan had gone through since 1979. I believe in the power of fiction and began to think about a way to show people the impossible choices facing some Afghans and others during that time, by framing it in a (hopefully) compelling story with fully formed characters.

“As an avid lifelong reader, I’ve also always looked for universal themes in novels, such as personal identity; the weight of family myths and legacies; gray moral areas; the dangers of hubris; and our unwillingness to see the truth when it conflicts with our beliefs. My grandfather was an important figure in 20th-century Afghanistan, and although he died when my dad was only 14, he held considerable influence in how my father charted his own life. I was aware of the power of family narratives, and I wanted to capture that power, along with fundamental themes and political history in a single story. The result was THE OPIUM PRINCE.

“Much of it is drawn from my personal recollections, which are still quite vivid. I also relied on stories and memories shared by my aunts and uncles, who were immensely helpful. I was only eight when we left Afghanistan, so I needed the ‘grown-ups’ to confirm or add to my memories about neighborhoods, homes, markets, and streets. As to Afghan society, including ethnic divisions, I know about those things the way one knows about one’s society: through my lived experience and the experience of those close to me.

“That said, I also did read a lot, not least to confirm or correct what I thought I knew. One of the most valuable things I found during my research was an out-of-print Lonely Planet! I was looking for details about 1970s shopping, hotels, and sites in Afghan cities, but there were hardly any travel books about Afghanistan at all. The Lonely Planet guide contained a lot of local detail and references to places that don’t exist now after decades of war.”

That wasn’t all she had to research. THE OPIUM PRINCE is placed at a very particular political and cultural tipping point in Afghan history, and she wanted to make sure she got it right: “It was definitely challenging. The most frustrating thing is that when you try to find scholarship, journalism, or fiction about Afghanistan, so much of it is about the Taliban or things that either led to or followed 9/11. It’s as if the country didn’t exist before it got on America’s radar, or like there’s nothing going on there other than terrorism. To be sure, excellent academic research has been done on Afghanistan, including from some outstanding Afghan scholars, but there isn’t very much of it, especially on the pre-Soviet War era. In addition, almost all the Afghans in my life left the country in the 1970s, and the people my father knew in the Afghan government either died, withdrew from the public eye, or vanished.

“But I knew THE OPIUM PRINCE wouldn’t be compelling if I didn’t frame the time and place properly. The 1970s are sometimes referred to as the country’s Golden Age, and for good reason. It was relatively stable and ended with the April Revolution that heralded the Russian invasion, from which Afghanistan has never recovered.

“I wanted to capture the ordinary charm and tedium of daily life as well as the simmering tensions that exploded at the decade’s end. The actors and events I describe (like USADE and the street protests) are fictional, but they had to be rooted in the authentic tensions of that time and place.

“I searched online until I came across the names of a few former US government officials who had been part of aid projects in Afghanistan in the 1970s. I reached out and was thrilled when they replied. I also reached out to professors specializing in Afghanistan who had both scholarly knowledge and personal memories. I couldn’t have written the novel without their input.

“The most surprising thing was discovering how much I didn’t know or didn’t understand. I discovered my own biases and false assumptions. For example, there is tremendous diversity between Kochi nomad groups, economically as well as culturally. No one ever talked about that in the Afghanistan I knew. Many assumptions society made about them just reflected ignorance and prejudice.”

One of the major themes in the book is Daniel Sajadi’s struggles with his mixed identity. Did she ever feel any of that herself?

“Very much so. Not being ‘from’ anywhere has been a defining aspect of my life. People ask me if I feel rootless or miss having a homeland. The answer is no, because I don’t see the obvious advantage of being from one place instead of many. Plus, I don’t know how that feels, so I can’t really compare how I ‘feel’ with how others feel.

“You may have heard of the concept ‘third culture kids,’ and there are more of us now than when I was a child. Back then, especially in Europe and European schools, we were very much an anomaly. The prejudice and racism were totally overt. The teachers were much worse than the kids; when I was in the sixth grade, we ran into my teacher in the street one day and I said hello. She turned her back to me and told her friends that I was ‘that mongrel I was telling you about.’ There are many more examples that would shock you.

“It was also rough moving to the US at age 11 and not understanding any of the cultural references the other kids shared—games, sports, theme songs from TV shows, even clothing brands that were more or less acceptable and that signaled what clique you were in. The importance of being ‘popular’ was alien to me. Kids talked about that like it was a major goal in life. We lived in LA, so lots of girls were going to become movie stars, and there was this huge emphasis on appearance when we weren’t even in our teens yet. I was definitely on the outside, and in middle school I was mercilessly bullied. I’d like to think there is more awareness and sensitivity among youths now, and that it wouldn’t be as bad for a kid like me today. But we still have a deep societal problem with bullying at the highest level—those in power abusing the marginalized both directly (e.g., police brutality) and indirectly (e.g., socioeconomic structures that are all but impossible to break free from).

“I think you easily develop universal empathy if you’re from many cultures, especially ones that are very different from each other. I’m half-Swedish, and Sweden is also very important in my life. I have inherited or adopted many views that are associated with Swedish society, such as a strong egalitarianism and progressive views on women. Afghan society, as a whole, decidedly does not have progressive views on women. Sweden is in the top group of nations for standard of living, and Afghanistan is consistently at the bottom.

“The two societies are drastically different. And yet I have seen the best parts of both. In Afghan society, there’s such a powerful sense of solidarity that extends to all human beings and that translates into hospitality and a willingness to help complete strangers. During the Soviet-Afghan war, we’d hear about Afghans with very little money or food who would come upon a wounded Soviet soldier and take him in and nurse him back to health. That type of kindness and sense of obligation to others—even toward an enemy—exists in the West too, but not to the same degree. Ultimately, what you learn at a visceral level when you’re multicultural is that everybody is equally and fully human. That may sound obvious and trite, but it’s actually one of the hardest things for people to grasp. That everyone is fully human is a revolutionary notion.

“Sometime in my teens, I became aware that I didn’t view the world the way a lot of my friends did. To me, it was always a given that there was more than one way of seeing things, that you had to compromise, and that most people just want to be healthy and peaceful and have opportunities for their children.

“I can’t relate to conventional nationalism, for example. I am even uncomfortable rooting for ‘my’ team when I’m watching a game! I can better relate to rooting for an idea or a principle. To me, true right and wrong should be about reasoning and compassion. It ought to be universal and accessible to us all.

“In my writing, I hope to always create characters who force the reader to see the world in a way that might be uncomfortable because it challenges their preconceptions. I want my novels to convey the perspective of people they might normally not relate to or encounter.”

Aimaq’s literary influences reflect that determination, though they’re broad and sometimes unorthodox: “They change all the time. I can’t say where THE OPIUM PRINCE came from exactly, but I actually didn’t envision it as a crime/thriller story. It evolved that way without my even noticing, although it isn’t a classic example of the genre.

“I’ve always been drawn to stories about morally conflicted men, and especially loved Richard Ford when I was younger. Then I discovered Nicole Kraus, who is in my view our finest living writer; she is a genius at telling stories about legacies and being haunted by history, and she writes with lyricism. These things are important to me too. Language is very important. Writing is not just about telling a story; it is a tribute to language. The rhythm of sentences is almost too important to me, because sometimes I prioritize that over the actual content! Thankfully my editor at Soho (Amara Hoshijo) was good at tempering that tendency.

“I discovered the works of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie after watching her amazing TED Talk online. I am trying to understand how she makes a story feel so immediate and so vivid that you feel you’re there even though you’ve never been to the country in which it’s set. Her stories are extraordinarily immersive and I strive for that too.

“The writer I feel most connected to these days is Mohsin Hamid, although I won’t flatter myself by comparing THE OPIUM PRINCE to his books any more than to Adichie’s. His work is so thought-provoking and offers difficult perspectives on complicated protagonists. I’d like to achieve the same thing in my writing.

“I also have huge admiration for the great crime and legal-thriller writers who can spin a yarn and create a puzzle that the reader pieces together with the author’s guidance. This is so hard to do, and people like Michael Connelly and John Grisham are just masters of the craft. I read them whenever I have a chance. Since I call LA home (and the Valley specifically) I especially love getting lost in a Connelly book.”

I’m always interested in a writer’s journey through the publishing process—how they came to find first an agent and then a publisher. Some of the stories are odysseys, fraught with pitfalls, and some are much smoother. Aimaq’s was a bit of both.

“I am quite jealous of the ones who had a smooth experience. Mine was actually a two-headed beast: half-smooth and half-odyssey. I did get an agent really fast. I sent queries to dozens of agencies. I had never published anything, not even a short story. I was warned by writer friends that I would not find representation that way, and should prepare to go to conferences and hustle in person. I got ready for a long and arduous process. But I ended up with six offers from agents within a month, and more than 20 requests for the full manuscript. I signed with Jacques de Spoelberch after he had some of his authors, including the bestselling Joshilyn Jackson, email me to tell me he was the best. Which he is!

“Finding a publisher was tougher than we’d anticipated. I got a string of maddening rejections before Soho made an offer. That was the odyssey part. The maddening thing, besides worrying that I’d never find a publisher, was that the rejections had no common theme at all. One editor would say that my dialogue was brilliant, but my characters were bland, and another editor would say that my characters were fantastic but my dialogue didn’t work. What?! I’ve learned a lot about the subjectivity and unpredictable nature of the business. There’s definitely an element of luck.”

That’s something every writer discovers at some point in their career. Fortunately, Aimaq may not have to rely on luck much longer. THE OPIUM PRINCE is receiving considerable advance attention, and her second novel is already in the works. The “two-headed beast” may have been tamed at last.

*****

Neil Nyren retired at the end of 2017 as the executive VP, associate publisher and editor in chief of G. P. Putnam’s Sons. He is the winner of the 2017 Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Among his authors of crime and suspense were Clive Cussler, Ken Follett, C. J. Box, John Sandford, Robert Crais, Jack Higgins, W. E. B. Griffin, Frederick Forsyth, Randy Wayne White, Alex Berenson, Ace Atkins, and Carol O’Connell. He also worked with such writers as Tom Clancy, Patricia Cornwell, Daniel Silva, Martha Grimes, Ed McBain, Carl Hiaasen, and Jonathan Kellerman.

He is currently writing a monthly publishing column for the MWA newsletter The Third Degree, as well as a regular ITW-sponsored series on debut thriller authors for BookTrib.com, and is an editor at large for CrimeReads.

This column originally ran on Booktrib, where writers and readers meet: