On the Cover: Nancy Jooyoun Kim

Dialoguing with the Past and Present

By Dawn Ius

By Dawn Ius

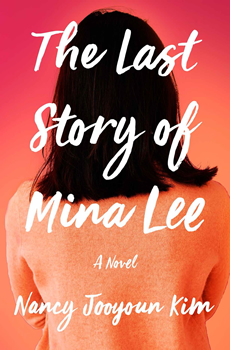

When Nancy Jooyoun Kim sat down to write THE LAST STORY OF MINA LEE back in 2011, she had no idea that this literary novel about a complex mother-daughter relationship would also include elements of a mystery.

“I always knew that the novel would begin with Margot, the daughter, finding her mother Mina’s body in their Koreatown apartment and that this book would be a dual narrative, alternating between the mother’s POV in the past and the daughter’s in the present,” Kim says. “But I didn’t have a strong sense of what Margot would be ‘doing’ in this book other than confronting who her mother was and who Margot will be now.”

Three years and a couple of drafts later, Kim realized that the book—which up until that point had hinged so much on the past—needed forward momentum in the present as well. More action. More plot.

The past and the present would then be in conversation with each other, Kim says, echoing the idea that both Margot and Mina are at turning points in their lives—Mina’s immigration to America and Margot’s discovery of her mother’s body.

“Margot would be against a system that doesn’t value her mother—a working-class single mother, an immigrant without a family—and she would spend this book attempting to understand what happened to her mother on the night of her death but also who her mother was while she was alive,” Kim says.

The result is a spellbinding mystery, beautifully written, peppered with authentic Korean culture, and subtly infused with a message that feels profoundly relevant in our current societal landscape: “Each individual and family has a story of migration and immigration that is unique to them, just like Mina and Margot’s. But what often ties these stories together is the human impulse to survive and to take care of our families. This impulse is universal and undeniable.”

To really home in on this message, Kim works in numerous moments of solidarity between people of color—a Sikh cab driver tells Mina to keep her fare on her first day in LA; Mina learns Spanish so she can communicate with her Latinx coworkers; she and her lover help an undocumented Mexican family find work and escape an abusive employer.

Each of those poignant moments helps to serve Kim’s greater purpose in writing the story.

“I wanted to write a book that centered on women, in particular, marginalized women—women of color, immigrant women, women who often work so tirelessly to care for and protect their families,” she says. “I myself grew up with a single mother, and I know the amount of sacrifice that women like my mother and Mina have made, how hard they’ve worked for so little, and yet still find beauty and joy in the everyday—love, magic, all those things that we yearn for and want out of life.”

Kim on an outrigger in Northern California’s Mendocino Bay, where Big River flows into the Pacific Ocean

As Margot learns, many of the things her mother yearned for never had the chance to come to fruition—her life, in many ways, was tragic. But Kim also wanted to demonstrate how complicated, and even successful, she was.

“She has extraordinary relationships and creates change for herself in bold and surprising ways,” Kim says. “She is a woman who writes her own story.”

Sadly, it’s a story largely misunderstood by her daughter, and in part, it’s this heartbreaking disconnect between the two women that creates such a compelling read.

“Sometimes it was very painful, but I simply looked as closely and honestly at these characters as possible and imagined what could happen between them: the things they say, the things they can’t say, and the things they regret,” she says. “Certainly some of Margot’s thoughts about her mother are ones that crossed my own mind when I was in my 20s. I feel terrible about that now. Thank goodness I grew out of that.”

Unfortunately, Margot doesn’t get the chance. Knowing that—which is, of course, not a spoiler—provides much of the intense emotion that drives the narrative. There’s action, too, but Kim takes us deep into the minds and hearts of these characters—so much so that we feel everything they feel, however nuanced.

“Mina’s POV was difficult simply because of her often painful experiences,” Kim says. “And there were times when I felt like I was writing to pull myself out of death, just how she continues to live and to find love, to write her own story, against all odds as well.”

Margot’s POV—while still robust and intimate—was easier to write, Kim says, because on the surface, she “has so much agency. But I also found it hard to capture her almost permanent state of dissociation.

“She had a rough and often joyless childhood, and as an adult, has been through such a traumatic event, finding her mother’s body and now dealing with her death. So the psychology, or really getting into the mindset of someone who is stunned, shocked, but yearning, deeply struggling as well, was tough.”

Kim leans on that yearning to flesh out Margot’s character. While trying to solve the mystery behind her mother’s death, Margot is reimmersed in the Korean culture she tried to avoid as a child.

“Margot wants to distance herself from Korean culture because she mostly experiences it through her mother, whom she associates with things like hard work, foreignness, poverty,” Kim says. “But as she spends more time in Koreatown for the first time in her life as an adult, and she gets deeper into her mother’s life and story, she realizes how rich and how beautiful the culture is, especially through food, and how much she can now learn about survival from their history and past.”

Kim heads back to Koreatown for her follow-up book, an as-yet-untitled story that delves into the “lives, the secrets and silences of a Korean American family still grieving the mysterious death of a mother five years ago.

“This book will also explore issues of homelessness through the lens of an immigrant family, struggling in their own ways to belong.”

- The Ballad of the Great Value Boys by Ken Harris - February 15, 2025

- Don’t Look Down by Matthew Becker - February 15, 2025

- The Wolf Tree by Laura McCluskey - February 14, 2025