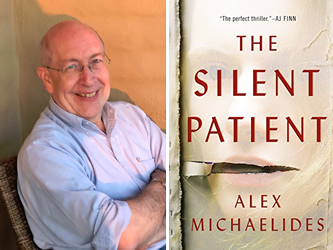

BookTrib Spotlight: Alex Michaelides

The Unraveling of a Mystery

and a Mind

Alex Michaelides grew up reading Agatha Christie “obsessively”—but Agatha never wrote anything like THE SILENT PATIENT.

Michaelides’s novel grips you immediately, taking you to dark corners of the human psyche you never knew existed. And where it goes is completely unpredictable.

“I love him so totally, completely, sometimes it threatens to overwhelm me. Sometimes I think—

“No, I won’t write about that.”

Alicia Berenson, a noted painter, is 33 when she kills her husband. Reported gunshots bring London police to a house where they find a man bound to a chair, shot several times in the face. A gun is on the floor, as is a bloody knife. His wife stands nearby, frozen, deep cuts across her arms. She refuses to speak. In fact, she never speaks again— not even at her trial.

Her only statement is a painting, a self-portrait done weeks later, titled Alcestis.

This immediately sends authorities scurrying for their reference books, where they learn that Alcestis was the heroine of a Greek myth about a wife who sacrificed her life for that of her husband. What does it mean here? Nobody knows.

Six years later, a forensic psychotherapist arrives at the secure unit to which Alicia has been committed—the Grove—determined to find out. A colleague warns him, “Be careful, mate. Borderlines are seductive. I don’t think you fully get that.”

The psychotherapist is undeterred: “Were they right? I felt confident the answer was no. I was perfectly able to remain objective about her, stay vigilant, tread carefully, and keep firm boundaries.

“I was wrong. It was already too late, though I wouldn’t admit this, even to myself.”

As he tries to unravel the mystery of Alicia Berenson, just how wrong he is turns out to be worthy of a Greek tragedy in itself—a very bloody one.

“Psychology has always fascinated me,” says Michaelides. “Which must be true for any writer. I was in twice-weekly therapy for about ten years, and I started studying it at a post-graduate level at a couple of different places in London. My sister is a psychiatrist, so she got me a part-time job at a secure unit for teenagers; it became an increasingly important part of my life and I ended up spending more and more time there. The only reason I quit was because the unit was closed down when all the cuts were made after the banking crisis. Otherwise, I would probably still be there now.

“Psychology has always fascinated me,” says Michaelides. “Which must be true for any writer. I was in twice-weekly therapy for about ten years, and I started studying it at a post-graduate level at a couple of different places in London. My sister is a psychiatrist, so she got me a part-time job at a secure unit for teenagers; it became an increasingly important part of my life and I ended up spending more and more time there. The only reason I quit was because the unit was closed down when all the cuts were made after the banking crisis. Otherwise, I would probably still be there now.

“It was a Therapeutic Community—which is a highly effective but not particularly cost-effective form of therapy, where, for example, a group of adolescents will stay at a unit for a period of up to four years, immersed in the community—which includes therapists, doctors, nurses—and where all activities and therapies are group-based, and all decisions regarding a patient’s care are made by the group. It’s a powerful healing process for these damaged young people, who suddenly find themselves, after so much abuse, in the bosom of a highly functioning and caring family. It’s an increasingly rare form of therapy, unfortunately, and it was a privilege to experience it. It changed me on a very deep level. I didn’t know I was going to write THE SILENT PATIENT then, and never used any of the stories or people I encountered there, but I kept a record of the atmosphere and my own emotional reactions. I used them in the novel and that was very helpful.”

That didn’t stop Michaelides from using elements of people he encountered elsewhere, though. His portrayals of the therapists in the book are very mixed—some of them smart and empathetic, and others decidedly not.

“Part of the reason I decided not to finish the training and become a psychotherapist was because I kept encountering—not at the unit itself, but in other places—people who were supposedly very eminent and who were venerated, who demonstrated a total lack of empathy or kindness. There were even elements of sadism that I witnessed. And this was a very important lesson for me, in terms of growing up: I had previously placed all my authority in ‘teachers’—people who were smarter and better-educated than me. And I learned that it doesn’t matter how important you are or how many letters you have after your name, if you don’t know anything about basic compassion, then you have nothing to teach me. So, yes, I think that ambivalence was definitely playing out in my mind as I wrote the novel.”

As was the other main driver of the book—the myth of Alcestis.

“I grew up in the Greek part of Cyprus, which is a very ancient place, and immersed in the Greek myths. You are taught Homer from a young age and the tragedies are constantly being performed and re-interpreted. I came across the myth of Alcestis—a woman dying for her husband and then coming back from the dead—at about the age of 12, and it’s haunted me ever since. It’s about love and loss and resurrection—and also betrayal. Alcestis doesn’t speak after being resurrected and her silence has been interpreted in all kinds of ways. I tried updating the story and writing it as a play, and then a short film, and then ultimately it found its form as the basis for my novel.”

The whale of an ending “was always linked to Alcestis for me—what happens after the tragedy finishes, and what happened before it began?”

“I grew up reading Agatha Christie obsessively, and I wrote THE SILENT PATIENT as an attempt to marry her brilliant plotting with a deeper emotional complexity. I still read her all the time, as no one is better at set-up and payoff. You can learn everything you need to know by deconstructing one of her books.

“I tend to outline a great deal, which is a method I learned at film school. It saves time, ultimately, so once you’ve done 20 to 25 outlines, the actual process is quite quick. It might not work so well if you want to be surprised during the writing, but for the kind of book I write—a detective story, essentially—everything needs to be planned meticulously. It feels closer to architecture than writing, sometimes.”

His film experiences also led him, not surprisingly, to films themselves.

“I love movies. When I was a child, I was convinced my life would be immeasurably improved if I could just get to Hollywood. And that fantasy drove me for the next couple of decades, for better or worse,” he says.

“It’s incredibly difficult to get a film made, let alone make a good one. The problem is that so many people are involved in every stage, and everything can and usually does go wrong. So with the best will in the world, a decent script with a great cast can slowly become dismantled by logistical and production problems, which is what I witnessed on a couple of occasions. It definitely drove me to write a novel—to experience being in charge of a project from start to finish and relying on no one but myself to see it through. It was a really satisfying experience, and the happiest one I’ve had as a writer. Having said that, I also learned a good deal about storytelling and structuring a plot from making films. They say the failures teach you more than the successes.”

The films included The Devil You Know, a 2013 dark drama featuring Lena Olin, Rosamund Pike, and Jennifer Lawrence, and a 2018 comedy, initially called The Con Is On, then retitled The Brits Are Coming, starring Uma Thurman, Alice Eve, Sofia Vergara, and Tim Roth, among others. As Michaelides alluded, neither left much of an impression on audiences, but one of the stars definitely left an impression on him.

“I met Uma Thurman on the set, and I probably learned more about screenwriting from her than from my three years at film school. She has a remarkable visual sense. And such a breadth of knowledge—she’s been starring in films since she was fifteen, she knows so much. She should be a director, really. And from watching her work and talking to her about writing, I started to think about how to dramatize or stage scenes in a more visual way. I also talked to her about THE SILENT PATIENT and she made several invaluable suggestions, such as making Alicia a painter, which really helped bring the book alive.”

Michaelides’s screen work isn’t done though. A major company paid a lot of money for THE SILENT PATIENT and, “I will be writing the script, yes. I’m excited about the prospect. I used to be rather rigid as a writer, but I’m not at all now, and am very happy to take the whole thing apart and put it together in a new way. It will be a different beast to the book, but that’s not a bad thing.”

It’ll also help him in his next book.

“It’s called Scarecrow. It’s about a series of axe murders at a Cambridge college. I’ve had a fantastic time researching it and I’m enjoying writing it. I hope it works out. But I’m nervous, of course. Agatha Christie said writing a murder mystery is like creating a recipe, and you don’t know if it will work until you cook it, and someone takes a bite. I think that’s very true. I’m hoping not to poison anyone this time around.”

So with all the meticulous outlining and recipe-planning, does that mean the actual writing of THE SILENT PATIENT was relatively easy? His answer is emphatic, and bears a powerful message to all other writers working on their first novels.

“The actual writing was where I nearly fell down. I put off writing a novel for twenty years because I didn’t think I could do it, and I nearly quit many times while writing it. Every day was a battle with a voice telling me to give up, and it frightens me how many times I nearly listened to it,” Michaelides says. “I think Stephen King said writing a novel is like crossing the Atlantic in a bucket, and he’s right. So if I can pass on any advice about the process, it is to make sure you don’t give up.”

*****

Neil Nyren retired at the end of 2017 as the Executive VP, associate publisher and editor in chief of G. P. Putnam’s Sons. He is the winner of the 2017 Ellery Queen Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Among his authors of crime and suspense were Clive Cussler, Ken Follett, C. J. Box, John Sandford, Robert Crais, Jack Higgins, W. E. B. Griffin, Frederick Forsyth, Randy Wayne White, Alex Berenson, Ace Atkins, and Carol O’Connell. He also worked with such writers as Tom Clancy, Patricia Cornwell, Daniel Silva, Martha Grimes, Ed McBain, Carl Hiaasen, and Jonathan Kellerman.

He is currently writing a monthly publishing column for the MWA newsletter The Third Degree, as well as a regular ITW-sponsored series on debut thriller authors for BookTrib.com, and is an editor at large for CrimeReads.

This column originally ran on Booktrib, where writers and readers meet:

- Africa Scene: Iris Mwanza by Michael Sears - December 16, 2024

- Late Checkout by Alan Orloff (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024

- Jack Stewart with Millie Naylor Hast (VIDEO) - December 11, 2024