Africa Scene: Jeff Dawson

No Ordinary Thriller

Jeff Dawson is a well-known journalist and author of non-fiction. He is a long-standing contributor to The Sunday Times culture section, writing regular A-list arts features that include interviews with the likes of Robert De Niro, George Clooney, Dustin Hoffman, Hugh Grant, Angelina Jolie, Jerry Seinfeld, and Nicole Kidman. He is also a former U.S. Editor of Empire magazine.

Jeff is the author of three non-fiction books — Tarantino/Quentin Tarantino: The Cinema of Cool (Cassell/Applause, 1995), Back Home: England and the 1970 World Cup (Orion, 2001), which The Times rated “Truly outstanding,” and Dead Reckoning: The Dunedin Star Disaster (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005), which was nominated for the Mountbatten Maritime Prize, and introduced him to southern Africa.

Turning his hand to crime fiction has been no less successful. NO ORDINARY KILLING, his debut novel, takes us to the Cape at the time of the Boer War and seamlessly weaves historical mystery and thriller. It became an Amazon Kindle best seller when it was released. I think we’ll be hearing a lot more about Jeff’s fiction.

NO ORDINARY KILLING is set in South Africa in 1899 at the turning point of the Boer War. You mentioned that you’re a history buff, but what attracted you to this particular period and setting?

A few years ago, in St Albans, England, I lived on a street called Ladysmith Road. It joined another one called Kimberley, both thoroughfares of solid, red-brick terracing. Show me any British suburb built around 1900, and I will give you roads called Ladysmith and Kimberley, Mafeking too – named after towns besieged, then jubilantly relieved, during the Boer War of 1899 to 1902.

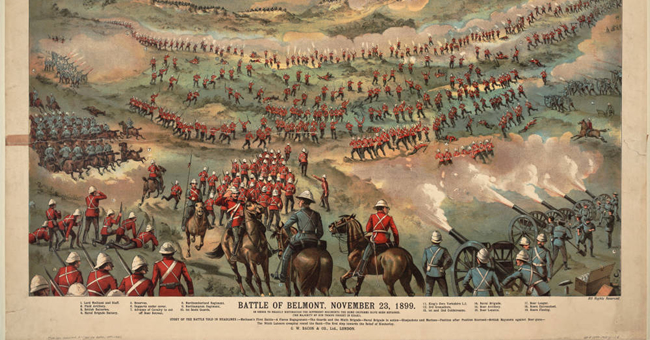

At the war’s peak, a staggering half a million men – half a million – had flooded into South Africa from around the Empire, the then-biggest military expedition in history. It was the Vietnam War of its day, in which the might of the world’s pre-eminent superpower was brought to bear upon a vastly outnumbered, supposedly ragtag foe. It was the first war in which Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, and other dominions sent troops to fight with the Mother Country (enthusiastically so). It was also a proxy war with volunteer international brigades afoot and the Boers armed by the Germans, such that the veld became a sort of testing ground for future horrors.

So part of the national psyche was the war that, on the streets of Britain, news of the relief of Mafeking prompted scenes of spontaneous patriotic celebration unmatched till VE Day. And yet today, in Britain (but not in South Africa!), the Boer War has been virtually airbrushed from history. There are reasons, of course. Firstly, it was an embarrassment, one internationally condemned — a lop-sided affair in which a vaunted brief victory ended up taking a brutal two and a half years, with thousands of Boer women and children perishing in that brand new construct, the “concentration camp.” Secondly, just 12 years later came the Great War, a conflict so cataclysmic, and so much closer to home, that this colonial rumble in a far-flung corner of the British Empire seemed irrelevant.

Having said all that, I must stress that the book isn’t about the Boer War. It’s a crime thriller set largely in Cape Town with the conflict as a backdrop.

You have clearly studied the areas where the novel takes place and the historical details meticulously. How did you go about researching not only a different country, but also a different time period there?

I wouldn’t give me too much credit here! It’s a lot of smoke and mirrors. One of the interesting things about the Boer War is that it was the first modern “media war” in which the telegraph and telephone were key components, relaying stories as they happened to news desks in London and around the world. It was a war that was extensively photographed, even filmed, and one in which public opinion (often hostile) played a huge part, influenced by “embedded” reporters like Winston Churchill. What I’m saying is there is a lot of contemporary reportage. It’s all there online. Of the published works, Thomas Pakenham’s staggering 1979 book, The Boer War, in particular, is a treasure trove of information. I’d been to South Africa and Namibia a few times in researching my previous book. I found it a fascinating place and I hope I soaked it up a bit. It seemed a great setting for a story.

When it comes to writing history (and I’ve applied this to my non-fiction work, too), another key thing is to remember that characters in the past don’t know they’re living in the past. For them, they are living on the cutting edge of modernity. Of course, technology changes, dress changes, codes of behavior change, but human hopes, fears, aspirations and emotions are timeless. The history is just set dressing!

Plus, 100-odd years isn’t that long ago. In terms of the look of a place, the buildings, etcetera, a lot of the historic heart of Cape Town is exactly the same as it would have been then.

There are two interlinked threads to NO ORDINARY KILLING. In the one, Captain Ingo Finch – a doctor in the Royal Medical Corps – becomes involved almost by accident in the investigation of the murder of his commanding officer Major Cox in Cape Town on Christmas Eve. The other follows Mbutu – a black man – who is dragooned into helping a mysterious lieutenant out of Kimberley past the Boer siege.

They see the war and its participants from quite different perspectives. Was juxtaposing these viewpoints part of what you wanted to achieve in the book?

I thought it would be interesting to have different viewpoints, yes. The characters are both outsiders and in a strange way share a lot of similarities – they’re both caught up in a war they neither fully understand nor approve of and are trying to do something noble in the midst of it all. For that to work they each have to maintain a degree of objectivity.

I needed Finch to be slightly detached – with the Army, but not of the Army, if that makes sense. He’s there to do a job without necessarily approving of the overall objective. I could have made him a padre or a war correspondent but opted for a medic. The Boer War was the first war in the which the Royal Army Medical Corps was suited and booted in khaki as an army unit rather than a bunch of civilian volunteers, so that was quite interesting, too.

And as for Mbutu… He’s a classic war refugee, displaced, on the run, and just wanting to get back to his family. The biggest casualties in any war are civilians. History seldom records their plight. We rightly condemn the horrors of the concentration camps and the deaths of the Boer women and children, yet twice as many black Africans perished in internment camps without much note. It reminded me of something in the early 1990s – how while the Bosnian War was raging and the world turned its outrage upon the ethnic cleansing going on in Europe, the Rwandan genocide was proceeding without any intervention.

From a Victorian British perspective, the Boer war was very much regarded as a conflict between “European peoples,” despite the fact that it was occurring at the far tip of Africa. The rest were all just “extras.”

The book starts as a classic mystery, almost reminiscent of Sherlock Holmes himself – there’s even the search for the mysterious Moriarty! Major Cox has obtained certain information that will greatly embarrass the war office and the government, and they are desperate to get it back. Pretty soon it becomes a thriller as Captain Finch and his companion Nurse Jones are targeted. Did you set out to marry the two genre styles or did the story just develop that way?

I’m never sure about genre classifications. Is Romeo & Juliet a Romance or a Tragedy? The story goes where the story goes! One of my favourite books is Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five. It’s about a POW’s experiences during the fire-bombing of Dresden, yet it also features time travel, space ships and alien planets. Regarding Sherlock Holmes, by the way, don’t forget Conan Doyle was there as a medic and war correspondent (a very biased, patriotic one). I gave him a walk-on.

Your sympathies are more with Mbutu and the Nama people with him than the British colonialists. As an Afrikaans lady who runs the boarding house in Cape Town where Major Cox lodged says: “The British seem very convinced that they can just walk into a stranger’s house and put everything to right.” Would you comment?

Believe me, I’m not some trendy liberal decrying every aspect of the Empire. Clearly there were some unspeakable injustices conducted in Britain’s name around the globe, but there were also some positives – that’s an argument for another day. What is fact is that by the end of the nineteenth century, Britain was the most powerful nation on Earth, and by some distance. It had positioned itself as the world’s policeman, much as America does today (although we have some tectonic plate shifting going on there now, too). There’s a swagger that goes with that role, going in to sort out a perceived “problem,” often at the expense (and ignorance) of local and cultural sensibilities. There’s a vestige of that today in some of Britain’s foreign policy overreach (however sincere the intention), although the cry of “imperialism” is often just a handy stick to be wielded by naysayers.

Ans Du Plessis was an interesting character for me. She has a line: “There have been Dutch here since 1652, Portuguese since the 1480s. There have been Europeans in South Africa longer than they have been in the Americas. For some reason, history has never accorded us the same legitimacy.”

People forget there were thousands of Cape Dutch happily living under British colonial rule in the Cape Colony and who’d done very nicely – the renegade Boers were as much an irritant to them as they were to the British. It was not a cut-and-dried us-versus-them situation. In any revolutionary war, there is always a substantial body of loyalists and just-keep-your-head-down neutrals (America, Ireland, etc.). They just don’t get ballads written about them.

Finch accepts the British philosophy of the day, but he has a more compassionate outlook than his colleagues – perhaps because he’s a doctor. This enables him to interact with different groups in Cape society and helps him with his quest to find the motive for Cox’s murder. How did you go about keeping Finch consistent with the times yet still create a sympathetic character that today’s readers can relate to?

I would say he accepts the existence of the philosophy rather than, necessarily, the philosophy itself. That goes back to the earlier point about him being detached – an objective non-combatant and one with a certain degree of privileged access by virtue of his profession, someone people defer to. Also confidentiality is his stock in trade and he must be extremely diplomatic regarding his own thoughts and prejudices. He’s our (unholy) innocent. We’re sort of seeing the war through his eyes. And, by the way, through those of Nurse Annie Jones. She’s another one seduced by adventure but who comes to question the whole point of the grand imperial exercise. She has equal footing in this story with Finch and Mbutu.

The Boer war – because of the mass media exposure – was probably the first war in which the British public didn’t buy the Government hook, line, and sinker. Yes, the response was generally patriotic, fueled by the jingoistic dispatches from the likes of Conan Doyle and Kipling. But there was definitely a skepticism afoot, certainly in the wake of the Hobhouse Report. There were anti-war marches of all sorts. Finch is quite modern in that regard and perhaps sees the situation more like we would today. His deep cynicism can’t be open though. He has to keep a lid on it most of the time.

Mbutu was actually my favorite character. Although he is separated from his family, beaten up, shot at, and treated with contempt, he watches the white people go about their business with an almost academic curiosity devoid of rancor. To me, this rings completely true of the people of the time. How did he develop?

I’m glad you liked Mbutu. Thank you. He does suffer a bit, admittedly. I think one of the things that outsiders to South Africa naively assume is that the black population is one unified entity. As we know, the original indigenous inhabitants of the land we now know as South Africa were the Bushmen (in their various subsets), here represented in latter-day equivalence by the Nama people. They are ethnically different to the Bantu peoples who later migrated into the area. Within black South Africa there is a multitude of ethnicities, religions, languages, cultures. Again, in Britain, there is a very simplistic black-and-white view of ethnicity (literally), probably amplified by South Africa’s years as a pariah apartheid state.

I wanted to use Mbutu to convey a sense of the complexity. In today’s language he’s an “economic migrant,” who’s gone to Kimberley for work, a long way from his home in Basutoland (Lesotho). And then, on the run, he’s suddenly a refugee, a black man alienated by other black men (the Nama) whom he self-consciously deems to be more “African” than him. Really, he’s just an urban man as lost in the bush as any city dweller of whatever race. His greatest value to the Nama comes as being an interlocutor, an interpreter of the white man’s ways. Yes, he’s a thoroughly decent chap who just shrugs his shoulders and gets on with things, unfazed by the foibles of his white masters. The Boer War is “their” war, a squabble between two white tribes.

One thing I like about Finch is that he tries so hard to treat both Annie and Mbutu as equals – as he feels he ought to (PC before his time) – but is so utterly clumsy in doing so. From their perspectives he’s just another stick-up-his-bum British officer.

Are you working on further historical fiction, and if so, will it also be set in South Africa?

I did a book a few years back called Dead Reckoning, a survival story about the wreck of the Dunedin Star, which went down off the Skeleton Coast of Namibia (S.W.A.) in 1942. South Africa featured heavily in that. So that’s two on the trot! The next Finch novel, which comes out in September, is set back in England two years after the Boer War ends, but it has many references to the conflict. Citing Vietnam again, one of things about the Boer War – or Second Boer War if we’re getting technical – is that these returning soldiers didn’t necessarily feel like heroes. They’d served their country, but for what? I’m not suggesting they grow their hair and start smoking pot, but self-loathing and drink do come into the equation! So, South Africa will be there in spirit if not location. But what an amazing country. I’d love to write about it again. And who knows, Finch may return elsewhere on the continent.

I’m looking forward to meeting Finch again soon!

Follow Jeff on Facebook (JeffDawsonAuthor), Twitter (@jeffdaw) and visit his website jeffdaw.wixsite.com

- Out of Africa: Annamaria Alfieri by Michael Sears - November 19, 2024

- Africa Scene: Abi Daré by Michael Sears - October 4, 2024

- International Thrills: Fiona Snyckers - April 25, 2024